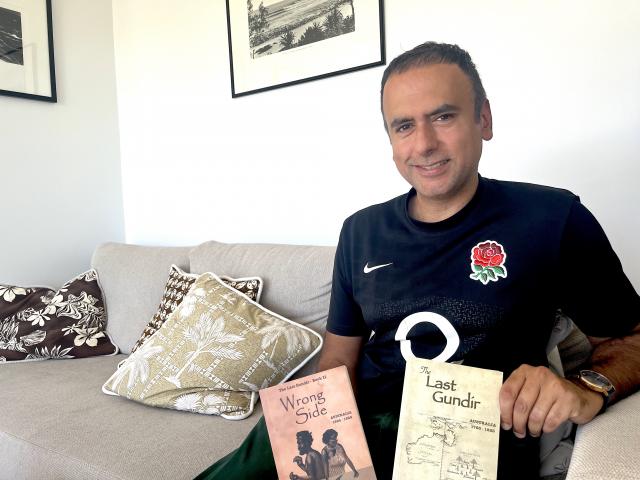

Born in Kuwait of Pakistani parents, a refugee of the Iraqi invasion at the age of nine and a midshipman in the British Royal Navy before leaving his teens, author and civil engineer Nayef Din had led an exciting and at times charmed life before fetching up in Brisbane in 2008 to work on a now iconic skyscraper.

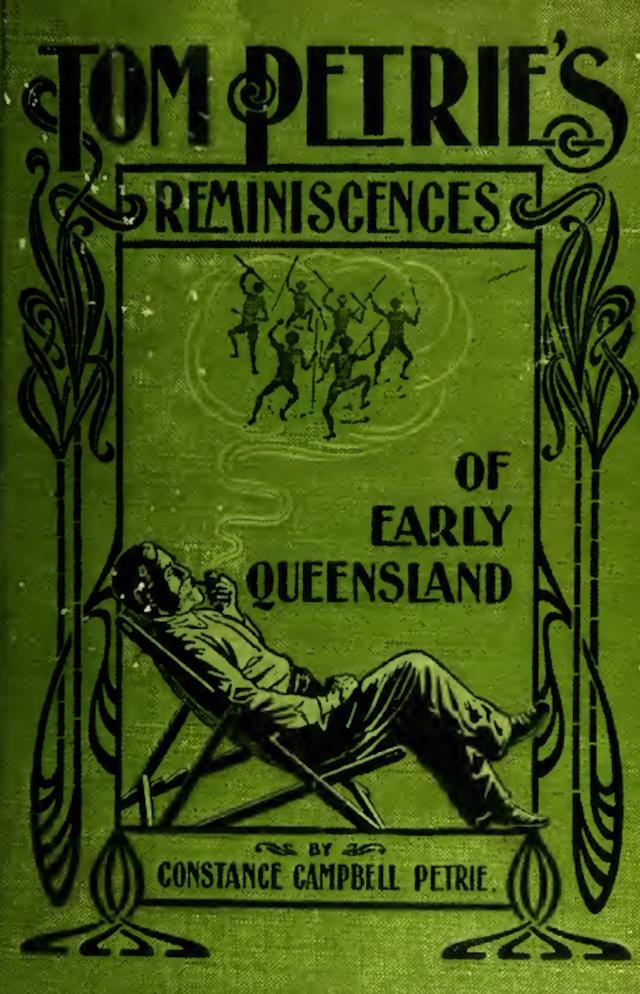

His real-life adventures are as breathtaking as those to be found in his two self-published novels, yet asked to nominate a defining moment in his life, without hesitation he recalls a visit to the giant Bookfest at Brisbane’s South Bank a few years ago. He says: “I’d become interested in Aboriginal culture but I could find very little about it, until one day, as luck or divine intervention would have it, at Bookfest I picked up a very old book called Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, written by his daughter, Constance Campbell Petrie. I bought it for two dollars and it’s the best two dollars I’ve ever spent. It beautifully captures what it was like for a young boy growing up in the early years of the colony, when the Aboriginal culture was relatively pure, it hadn’t yet been tainted by missionaries or anything else. That book gave me a place to start.”

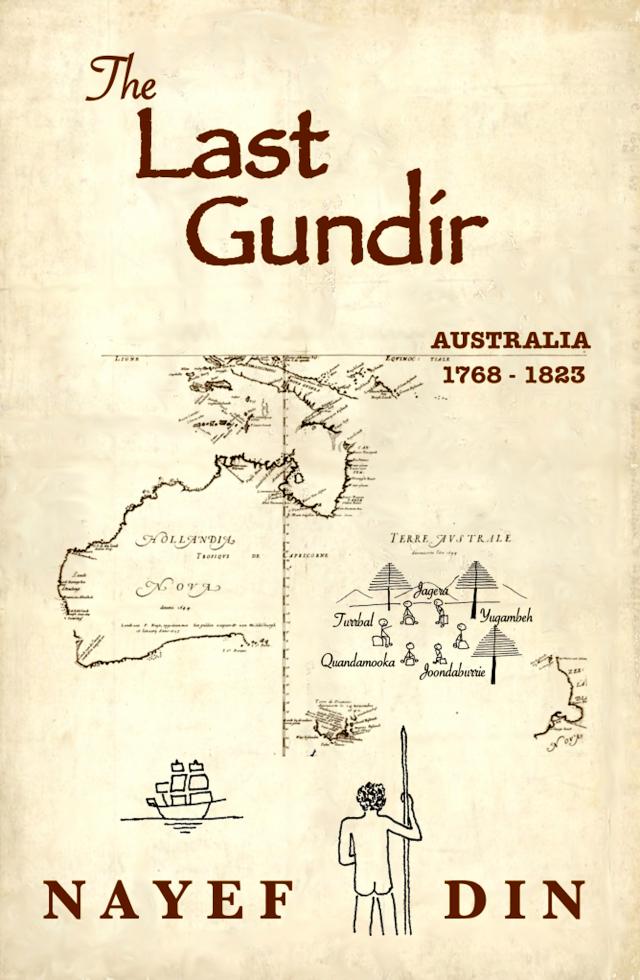

The near miracle of finding the extremely rare print edition of the 1904 Petrie classic, a true motherlode for Queensland historians, started Nayef on a long creative journey, with many twists and turns, that has led so far to the publishing of the first two books of a projected trilogy – The Last Gundir in 2020 and Wrong Side (2022). Both are impeccably researched historical novels that combine stories of pre-colonial Aboriginal life in southern Queensland with a fresh look at Captain Cook’s arrival and the European settlement that eventually followed.

Writing such dense and complex works and selling them himself at city market stalls might seem a million miles removed from the career trajectory you might expect from this charming and talented man. Or maybe not. Expect the unexpected could well be his mantra.

When the Iraqi tanks rolled into Kuwait City in August 1990, provoking the First Gulf War, Nayef and his three siblings were living a comfortable life in a fashionable part of the city while his father earned a solid and untaxed salary as a civil engineer. His mother, a psychiatrist by profession, had elected to be a housewife and stay-at-home mum for the duration of their time in the Middle East, which they now realised had come to a sudden end.

The family fled to London, taking up residence in upscale Hornsey in North London. But Nayef’s father died unexpectedly soon after their arrival, and while his mother, whose qualifications weren’t recognised by the British medical authorities, went back to school to gain her registration, the family struggled. Nayef shrugs off the tough times: “You learn to adjust your standards. But I have so much admiration for how hard Mum worked to pull us through.”

Able to work as a psychiatrist again, she soon had the children in private schools, driving them there and to sports engagements in the car she had just learnt to drive.

After finishing school Nayef graduated with a master’s degree in civil engineering from Imperial College while simultaneously serving two years as a midshipman in the university’s Royal Navy unit. After graduation he took a gap year to study French at the Sorbonne in Paris, where the students had to also take up a course in an unrelated subject and complete it in French. Nayef recalls: “From a long list I chose the history of Paris, and I loved learning about what the city looked like hundreds of years ago. I think wherever you live, you should know the story of that place, so I learnt the history of Paris, then when I went back to London to start my engineering career, I learnt that city story too.”

Nayef secured a job in London at the global headquarters of engineering giant Arup where he acquired skills in cutting edge technology such as top-down construction. In 2007 this led to an email out of the blue from the Arup office in Brisbane where they were about to begin work on a groundbreaking skyscraper called 111 Eagle Street which required expertise in top-down. Putting the call of adventure above his misgivings about a small city on the other side of the world, Nayef accepted a two-year contract and arrived in Brisbane in early 2008.

He loved the city and he loved the work, moving from 111 Eagle St to AirportLink, a mammoth job that Nayef describes as “complex but one of the most enjoyable jobs I’ve ever worked on”. He also made the time to continue his history of place theory. He says: “In Brisbane my initial idea was to study the history of the city, its floods and bridge collapses, the whole thing. I was living in Milton in 2011 during the floods and had to be evacuated, so that spiked my interest even further. But I was also developing an interest in Aboriginal culture, and that’s what led me to Bookfest and Tom Petrie.

“Petrie’s Reminiscences was a nugget of gold in the rabble for it revealed a fascinating world right where I lived. It furnished details of an idyllic, extraordinary society that lived in total harmony with the environment here for tens of thousands of years. I felt inspired to write a story set in that world to invite the reader to learn more about this highly evolved civilisation that thrived on spiritual rather than material values. I found the kinship system and the totemic responsibilities truly remarkable and arguably important to understand in today’s world. How would the world look if we all showed the same kindness to strangers and looked after the environment in the same way?”

Nayef’s research led him to other worthy tomes on Indigenous life, but it was a human connection that helped steer his literary work, forged when he met Turrbal songwoman and elder Aunty Maroochy Barambah, who became his mentor in understanding the fundamentals, to such an extent that in 2017 she presented him with an award from the Turrbal people for his role in raising awareness of Aboriginal culture in Brisbane.

But Nayef also wanted to tell the backstory of the coming of the white man, of Cook’s exploration of the east coast and subsequent proclamation of sovereignty for King George. In London for six months in 2018, he took the opportunity to study Cook’s journals at the British Library. He recalls: “I requested the journal and used it as a blueprint for my Cook chapters, but when Cook came to the proclamation on Possession Island in the Torres Strait, his account is very dry, literally one paragraph. I knew that Joseph Banks wasn’t just a botanist, he was an eloquent diarist, a man who wrote down everything, so I then requested the Banks diaries and went straight to the date of the Possession Island ceremony, and Banks doesn’t describe it at all. He describes going to the highest point of the island but only to chart a passage through the sandbars for their departure. I was quite stunned.”

Further research revealed that Cook had fabricated an account of the “proclamation” and inserted new pages in his journal after hearing in Batavia (now Jakarta) some months later that the French explorer Bougainville had followed the same coast en route to Tahiti, and had possibly claimed the new territory for France, the arch enemy of Britain. The research also revealed that a few months earlier a book called Lying For The Admiralty, by Margaret Cameron-Ash, had made the same claims. So Nayef didn’t own the discovery, but his knowledge of it informs a large chunk of The Last Gundir and offers a new perspective of what that means now.

Back in Australia Nayef was on the home straight with his first novel, so he took time out from engineering to devote himself to finishing the manuscript, which he then sent to several publishers. Then a friend suggested that, given the Queensland focus of The Last Gundir, University of Queensland Press might be interested. Nayef sent a submission to UQP, only to have it rejected by an email which Nayef says stated “that as I was not Aboriginal they would not be considering my manuscript and didn’t want to see it.” A subsequent new submission accompanied by a letter of support volunteered by Maroochy Barambah fared no better.

Says Nayef: “Aunty Maroochy’s letter of support nevertheless enabled me to get back on my feet and make the decision to self-publish. I printed a small batch at a Brisbane printer and started selling them myself at markets. It was slow going at first but I sold 500 and reprinted, and now I’m around 1400 sales, with good reviews coming in.” Sales of the sequel, Wrong Side, available since the beginning of this year, are “slow but picking up”.

At the same time as Nayef was picking himself up after the UQP rejection, another literary cultural appropriation issue was playing out in the US over the bestselling novel American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins. Here the issue was about an American woman, albeit one with strong Mexican connections, writing about, not Indigenous cultural affairs but about a Mexican woman and her young child fleeing the violence of the drug cartels. I read the book before the dirt hit the fan, so to speak, and thought it was brilliant. The New York Times and the woke radicals didn’t, labelling it “trauma porn”.

Says Nayef Din: “I don’t understand the kind of thinking that equates the colour of your skin with cultural appropriation. If that was applied universally, how many great books would not have been published? [Answer: a great many.] In my case, born in Kuwait of Pakistani parents and schooled in England, I could only write about Kuwaiti, Pakistani or English characters. It doesn’t make any sense.”

The Last Gundir is a complex read, with perhaps too much explanation of what it is trying to achieve, rather than leaving that to the reader to determine. UQP, had they agreed to read the manuscript, may have rejected it anyway on those grounds. But they didn’t give it a chance. I have nothing but admiration for the 42-year-old author, who can really write, and has put it all on the line to present a new vision of Queensland’s pre-colonial and colonial past. I’m still catching up with Wrong Side, but it seems to share the same qualities.

Neither book is likely to have mass appeal, but if you’re interested in some fascinating insights into our First Nations and early colonial past, wrapped around a well-told coming of age story, I strongly suggest you take the journey with Nayef.

The Last Gundir and Wrong Side are both available from Annie’s Books on Peregian and Berkelouw’s at Eumundi.