PHIL JARRATT concludes his search for Cherbourg’s lost history

At the very end of James Muller’s poignant 2019 documentary, Place of Crowes, Kabi Kabi man and Crowe descendant Brian Warner, standing on country at the edge of Lake Cootharaba, looks directly at the camera and says: “When you’ve got identity, you feel stronger.” He pauses, brushing away a tear, and continues with his voice cracking: “You have that sense of belonging.”

It’s a heartbreaking moment because anyone who has studied Indigenous history knows that without doubt we European Queenslanders stole not only the lands of the First Nations but the identity that went with it. We stole their sense of belonging, and nowhere is that better exemplified than in the lost history of Barambah Aboriginal Settlement, now Cherbourg Aboriginal Shire, the third biggest Aboriginal community in Australia.

Muller’s important film, funded by Noosa Shire Council, managed by Noosa Heritage Co-ordinator Jane Harding and researched by Crowe descendant Troy Georgetown, was the first real attempt to track the descendants of our Aboriginal pioneers, who were first humiliated and degraded by the white settlers of Noosa Shire from the 1880s and then were forcibly removed to Barambah in the first decade of the 20th century.

It’s a dreadful history, and it says much about the moral values and courage of the 2016-2020 Noosa Council that they were prepared to own it and fund this mea culpa. But it’s not enough. You only have to visit Cherbourg today and talk to people to learn that their stolen identity still creates a void that has impacted on the spiritual wellbeing of generations, and is still destroying lives today.

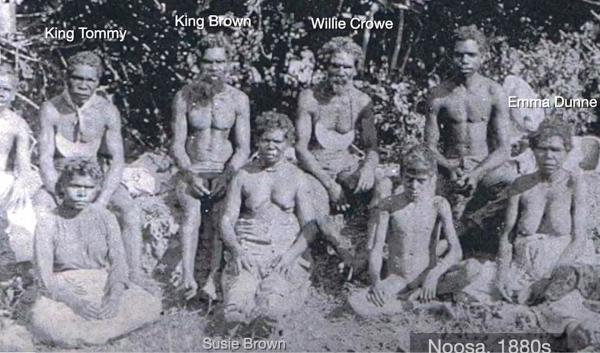

All we can do is try to help the healing, and this was at the back of my mind when I recently travelled to Cherbourg, less than two hours from Noosa, for the first time in 30 years. I wanted to get a feeling for the kind of lives people lived there over the five or six generations since the Kabi Kabi were expelled from their Noosa homelands, but perhaps more importantly, I wanted to try to connect the people of today with the faded old photographs we have of their ancestors, those confused, depressed and dispossessed people lined up for the camera with their insulting metal nameplates hung around their necks, sarcastically proclaiming them as kings and queens, concepts that were foreign to their culture.

Every time I look at such photos, I wonder how they felt about such ignominious treatment. They’d ruled this land by their own terms for 60,000 years and didn’t need a nameplate to remind them, but I wonder if they were truly insulted or if they simply and typically raised an eyebrow at the bizarre and baffling ways of the white man.

Photographer Rob Maccoll and I drove up to Cherbourg with Brian Warner, whose emotional closer in Place of Crowes made him a good place to start the conversation about identity. His identity. “Well, it’s complicated,” he said, dissolving into a guffaw that shook the car.

Indeed it is, but if you examine the early photos of the Tewantin Kabi Kabi elders, there seem to be three lines of family – those of King Tommy, King Brown and Willie Crowe (sometimes known as King Billy). But two of these “kings”, Tommy and Willie, were brothers and both seem to have been married at different times, or at least sired children to, the same woman, Emma Dun, often referred to as Dunne.

Although the authorities of the time seem to have misread Tommy’s nameplate, “King Tommy Noosa” to arrive at the conclusion that his name was Thomas King, it was in fact Barlow Crowe, and his father was Jim Crow, who had been a member of the first Aboriginal cricket tour of England in 1868, although he had to return home ill midway through the arduous season. The name being an adaptation of an American racial slur, there were plenty of Jim Crows around in the late 19th century, but dates and locations seem to confirm that the cricketer was indeed father to Barlow and his younger brother Willie.

Barlow worked as a timber-cutter in the Lake Cootharaba area, which was where he met Emma Dun, a housemaid at nearby Bundora Station, where she had taken on the name of the owners, Charles and Zorayda Dun, squatters from the Hunter Valley in NSW. According to historian Ray Kerkhove, whose work on the Kabi Kabi is the gold standard, this was common among Aboriginal household staff of the period, the name offering them some form of protection from the authorities.

By the late 1880s, however, Emma had moved on to younger brother Willie, and begun a family with their first child, Willie Junior, who was Brian Warner’s great-grandfather. You have to be careful not to skip generations in charting these families, because it is the Aboriginal way to just regard everyone from two generations back as a grandfather, grandmother, aunty or uncle, and even bloodlines can be ignored in the case of close family friends. It is, as Warner says, complicated, but it seems likely that after evading the police around Tewantin for some time, Willie Junior and his wife were removed to Barambah where they raised six children, including Brian Warner’s grandfather. Willie the elder and Emma both died and were buried in Gympie around 1910.

Says Brian Warner: “After it became Cherbourg and was a bit better organized, some of that generation managed to get exemption certificates so they could work outside the reserve. My mother was born at Cherbourg but during that time my grandfather won the Lotto and ended up buying a home out near Wondai. My grandmother and my aunties and my mum used to talk about those old times at that house, but when my grandfather died, they didn’t keep the house on, they just went back to Cherbourg. But that was the beginning of my family spreading out. I think they realized that there was more to life than just trying to survive.”

Norman Bond, the chairman of the Kabi Kabi Peoples Aboriginal Corporation, is of similar age to his colleague Warner and can trace his family tree back just as far, and while his line is slightly less complex, the very long life of his great-grandmother gave him a living contact with the beginnings of Barambah Settlement.

Elsie Williams was born on the Maroochy River in 1891, the daughter of Albert Williams of Tewantin and Mary Brown, whose father was King Brown, one of the elders of Noosa. In 1907 she was forcibly removed to Barambah as one of the early inmates, and later worked in the girls’ dormitory. Elsie married twice, the second time to Bob McGowan, and had 13 children, one of whom was Bessie, Norman’s grandmother, who married into the Bond family, another Cherbourg dynasty. Four generations of Elsie’s family still lived at the settlement when Norman was born in 1973.

He says: “I’m fortunate and privileged to be able to trace my family like this because a lot of people can’t. And I got to know my great-grandmother before she died here in Cherbourg in 1986 when she was 95. I was about 13 when she passed so I was fortunate enough to get that traditional knowledge and stories from her. She didn’t say a lot about the happenings of the early days, I think because she wanted to protect us from the negative stuff she witnessed. But I remember all the wise things she told me, they’ve stuck with me.”

Now 47 and a grandfather, Norman Bond has given up his trade as a carpenter and his most recent job in the local justice group at Cherbourg to put all his eggs in the same basket as his friend Brian Warner. And their mission is to secure a future for all the young people in Cherbourg who are in destructive despair. There are many avenues to achieve this, including traineeships in tourism and land care on country in Noosa and other parts of the Sunshine Coast, but none are without their challenges.

As of 2020, several young Kabi Kabi people from Cherbourg and the southern end of the Sunshine Coast were living in Noosa Shire during the week while completing land management traineeships working with Noosa and District Landcare at Pomona. Landcare traineeships are regarded as a pilot program for what might develop in the forestry management space.

Interaction between the communities of Noosa and Cherbourg is not a new idea. Sporting ties were pioneered by Noosa Heads surf club, which organises surfing and swimming trips to the coast for disadvantaged kids, while on the political level, during the last Noosa Council, the mayors of the two shires formed closer ties and jointly presented a motion of support for the Uluru Statement From The Heart at the Local Government Association of Queensland annual conference in October 2019. It was overwhelmingly passed.

Now, the scale of Noosa’s Indigenous tourism initiative takes the potential for closer ties, employment, and, eventually, for a return to country for those who desire it, to a new and historic level.

Whatever form it takes, Noosa should welcome and embrace this coming home, this completion of the circle.