PHIL JARRATT uncovers an interesting connection between the champion of the White Shoe Brigade and Noosa’s conservationists

While the long reign of Joh Bjelke-Petersen over Queensland will always be remembered as the time of the White Shoe Brigade, when a develop-or-perish mentality overtook the Great South-East and turned Surfers Paradise into one endless skyscraper, it is a little known fact that Joh and Flo had a soft spot for Noosa and the Cooloola region and were on a first-names basis with some of our leading conservationists.

Long before Joh became premier, Noosa Parks Association was pioneered by rusted-on Country Party men like Arthur Harrold, Jim Fearnley, Max Walker and Guy L’Estrange, and if these rather sedate sea and tree changers looked like a pushover to the development cronies, they hadn’t reckoned on the cunning and the connections that would become their trademark. They could open more doors in Premier Frank Nicklin’s ministry than the development lobby and the council put together.

By the end of the 1960s, alongside the 300-strong Noosa Parks Association stood the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, the National Parks Association of Queensland, the Australian Conservation Foundation and at least another dozen smaller conservation and community groups in a fierce battle to save the Cooloola Wilderness from sand-mining and development. The NPA teamed with Caloundra resident Kathleen McArthur of the Wildlife Preservation Society on a huge “Postcards to the Premier” campaign that resulted in more than 150,000 cards reaching the desk of the new Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, an achievement Arthur Harrold called “a masterstroke”.

It could have also created a permanent rupture in relations with the new Premier, except that the NPA men had become friends with Joh. In 1970, NPA helped establish a Brisbane-based sister organisation called the Cooloola Committee, and also formed an alliance with the Fraser Island Defenders Organisation. Together they put together a petition of 24,000 names in support of a Cooloola National Park, most of them drawn from marginal seats, and provoked a backbench revolt that threatened Joh’s premiership. Again, this might have scuttled the relationship, but Joh reversed his pro-mining stance and supported protection of the dunes.

Unlike most who had forced Joh into a corner, the NPA men remained friendly with the premier and he with them, and he soon claimed the park as his own idea. After the park declaration in 1975, the premier and his secretary, Beryl, took the government jet to Rainbow Beach on a few occasions, and, according to the ranger who accompanied them, Bjelke-Petersen actually wept at the beauty of the dunescape he had saved. And his government, for the most part, remained supportive of environmental outcomes in Noosa.

But not always.

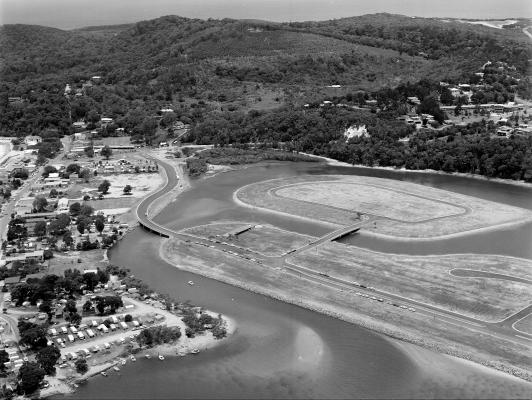

In 1964 two separate proposals had been put to Noosa Shire Council seeking approval for residential development on Hay’s Island, adjacent to Hastings Street. Both were rejected, but by 1969, the council took a different view and approved a proposal from a company called Noosa Island Estates, which was soon revealed to be a front for Australia’s biggest land developer and financier, Cambridge Credit.

The proposed development, to be known as Noosa Sound, was massive. It involved clearing the mangroves, dredging sand from the river to raise the land level by a metre, and the building of three bridges. It was expected to take five years to complete, with blocks of land then being offered for up to $10,000. The tender was officially accepted in September 1970 by the hard-drinking Minister for Lands, Vic Sullivan – later to be fired from the ministry for turning a ministerial visit to Torres Strait Aboriginal communities into a boozy fishing trip – who tossed a few down at the official announcement at Brisbane’s Park Royal Motor Inn and declared loftily: “Most of the area … is an unsightly combination of mangrove swamps, mud flats and sandbanks … the main breeding grounds for mosquitos and sandflies.”

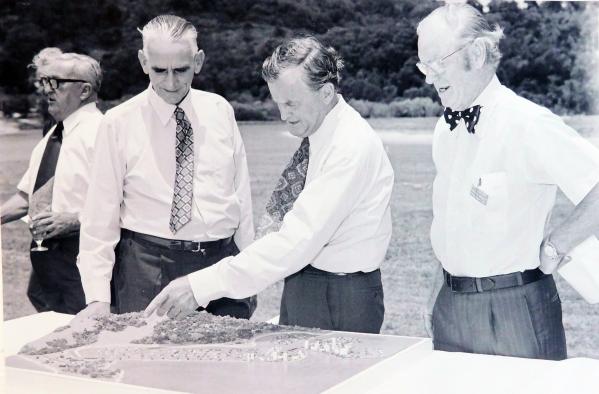

The first stage of the $3 million, 300-homesite canal development of Noosa Sound was opened by Premier Bjelke-Petersen in December 1973, with waterfront lots offered from $12,000. Speaking to a large gathering of dignitaries and salivating real estate agents, the premier continued the theme that “a former pest-infested area” had been transformed into “beautiful housing estate”. A month later Cyclone Wanda ripped down the coast and devastated Main Beach and The Woods camping area, and flooded parts of Noosaville and Tewantin.

Young solicitor Bob Cartwright donned his wet weather gear and stepped out of his new law office in Noosa Junction to inspect the damage. He recalls: “On the Sound, about 100 metres along, just opposite the Woods, the river level was so high it was lapping the top of the retaining wall, and when there was a set or a surge from the ocean, ripples would break across the road, and wash out holes in the gravel. There was no doubt that it was in danger.”

Although not many had seen what Cartwright saw, the rumour mill fed fears that a cyclone could wipe the place out, and Cyclone David in January 1976 forced the Queensland Government into immediate action to find a solution. Inspecting the damage with local MP Gordon Simpson a couple of months later, Premier Bjelke-Petersen vowed he would save the Sound, and so a problem created by man would have to find a man-made solution, despite the fact that for millennium beaches and waterways had done a pretty good job of sorting out the flow of sand for themselves.

The solution was that research conducted by the University of Queensland recommending “retraining of the river mouth” would be parlayed into a plan to lengthen the Noosa Spit and increase Main Beach by 500 metres, thereby moving the river mouth north and screening Noosa Sound from the force of ocean swell. It was a stupid plan on almost every level, creating a whole new raft of problems with sand movement and silting, and endangering marine ecosystems. But it won widespread approval and was adopted in 1977, its $1.4 million cost split between the state government, the council and the developers.

Joh was seen by many as the saviour of the Sound, and despite creating a problem that still plagues Noosa today, he retained his Noosa friendships, including one with Noosa News founder Sam Griffiths. In fact Sam was such a good mate that Joh allowed him to drive out to his Kingaroy property regularly and dig up white clay to use in his pottery.