Precede

In the concluding part of his shire ride, PHIL JARRATT takes in Pomona and Cooroy

Pomona

There’s only a hop, skip and a jump between them (well, about seven kilometres if you go the quick way) but the two neighbouring hinterland villages of Pomona and Cooroy have been rivals right from the start.

I was thinking about this I pedalled through the pretty Pinbarren countryside outside of Cooran through a light shower, on my way to a much-anticipated late lunch and a cold beer or two. It had been a long day in the saddle so far, but not wanting to arrive soaked I clicked the power up a notch and hit it down the much-improved road to town.

I checked into the pub (the second rendition, built in 1913 after fire destroyed the first), put my bike on the charger in a corner of the beer garden and took myself over to the nearby Village Kitchen, ordered a plate of salt and pepper squid and a Japanese Lager and spread my research notes over a corner table in the back courtyard.

Pomona’s original name, Pinbarren Siding, is testament to how little it mattered to our first settlers. When the railway came through in 1891, the cluster of timber-cutters and farmers on the foothills of Mount Pinbarren decided that the rail siding they had started to use – since local roads to the stations at Cooran and Cooroy were often impassable – to get their produce to market better have a name, so they gave it theirs, and Pinbarren Siding it remained until the new century, when the Queensland government approved the new name of Pomona, after the goddess of fruit trees.

It’s not known how the village’s most prominent residents took to it being named for an ancient Roman mythical god, the dozen or so landholders of the Protestant Unity commune being God-fearing fundamentalists, but it was to prove apt as fruit (especially bananas) became the staple produce of the region. By 1903 the former communards had 18 farms under their control and they ran the fast-growing town, which over the first decade of the century changed from a ‘wayside village, possessing only a small store and a village smithy’ to ‘a township vying with other places for premiership along the North Coast Line’.

In 1910, when Noosa Shire won independence from Widgee Shire (centred on Gympie), the first business of the new council was to select a permanent seat of local government, a role initially and temporarily granted to Cooran, whose Federal Hall had been the venue for the first election. But at the first meeting of council, the representatives of Cooran, Cooroy, Tewantin and Pomona all nominated to become the host of the council chambers. In a close vote, Cooroy won and started hiring contractors and buying timber from the Cootharaba mill to build the chambers.

But within a few months the decision had caused uproar throughout Noosa, with representatives of the other divisions presenting a petition to the Home Secretary demanding that Pomona be selected because it was more central, and had the biggest population of the shire with 450 residents. In a referendum on 11 March 1911, Pomona pipped Cooroy by 11 votes. As builders were sacked in Cooroy and timber sent back to the mills, Noosa Shire moved onto more pressing business, and Pomona and Cooroy agreed to disagree.

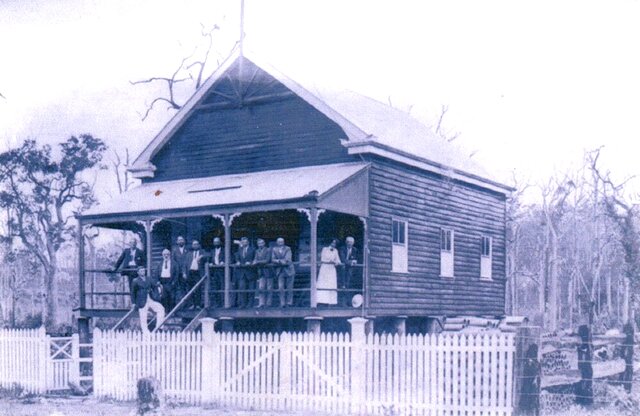

After lunch, I wandered across the railway line and down Factory Street’s heritage row to the original purpose-built council chambers, the oldest existing building in Pomona, which opened in September 1911 and remained Noosa’s seat of government until 1980, when it moved to it current home in Tewantin. The headquarters of the Cooroora Historical Society since 1985, and now a lively museum, the extended building retains much of its original charm, and I confess that over many visits I have spent as much time trying to imagine the process of government in these tiny rooms as I have looking at the exhibits.

On this visit, however, my attention was drawn to the artefacts housed in the Gubbi Gubbi (Kabi Kabi) Keeping Place, a Centenary of Federation project whose companion piece, the Gubbi Gubbi Island of Reconciliation, I had never visited. This meeting place, a circle of stones and a commemorative plaque on the banks of Cooroora Creek a few hundred metres from the museum, is a wonderful space of solitude and reflection. I just became aware of it more than 20 years after it was created, but hopefully many others have used it to reflect on our sorry First Nations history.

Cooroy

It had been a long time since I’d visited the Black Mountain precinct, a network of hilly roads where I used to train for distance running (including the King of the Mountain) half a lifetime ago, so I got an early start and took the long ride into Cooroy, shooting down the range roads with the rising sun behind me. Apart from the roadworks, it was as beautiful as I remembered it.

There was another reason for taking this route into Cooroy. It took me right past our first home in Noosa Shire, a beautiful transplanted Queenslander on a hectare of land sloping down to the left branch of Six Mile Creek. We dug a blue clay dam at the bottom of the property, put in a swimming pool next to the house and bought a ride-on mower. We loved it, but the country idyll couldn’t last. Our young kids joined every sports club in Noosa and we were constantly ferrying them back and forth. So we bought a place on the coast.

Our Queenslander is still much the same, add a few coats of paint, and Cooroy’s quaintness is still intact, if somewhat gentrified. But at 8am on a sunny autumn morning it was near impossible to get a seat in or outside a café. Beyond gentrification, Cooroy has become hip! Why wasn’t I told?

Tonguing for a coffee, I wandered down Maple Street hoping to find a café time had forgotten, and instead stumbled across an historical precinct I had forgotten, or at least knew very little about.

About eight years after my family left Cooroy for the coast, the Queensland government closed down the Cooroy mill, one of the last surviving and still productive timber mills in the state, a closure which cost the village more than 80 jobs. Nothing if not resilient, Cooroy fought back, and over the ensuing decades, the Lower Mill Site, largely under the direction of a committee now known as the Cooroy Future Group, has created a truly remarkable heritage precinct which not only brings to life the industrial history of the town, but blends it with the workshops of today’s artisans.

Okay, I knew all about the Butter Factory restoration and have been to events at the art centre, but I was truly gobsmacked by what I discovered just down the street. Very cool, and, given Cooroy’s roots in the 1880s as a mill town, very appropriate.

I still didn’t have a coffee but I grabbed one at the servo on the way out of town, and on a whim, I decided to do a loop around Lake Macdonald and see if I could connect with Old Tewantin Road and thus avoid the cycle-unfriendly newer one. Despite the best advice of Google Maps, you can’t without doing battle with the worst section of Noosa Trail 5, so I took a walk around the Botanic Gardens and doubled back.

It was a lovely detour and I survived the ride home, but note to council: it would be so nice to complete a backroad link and get cyclists off the main artery.

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win a Viking european river voyage valued at $16,190](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/viking-competition-wesbite-image-3-324x235.png)