PRECEDE

The good news is that tropical cyclones are becoming less frequent. The bad news is they are moving south! Phil Jarratt reports on ground-breaking local research.

Surfers love cyclones, especially the ones that keep a respectful distance and sit in the Coral Sea for a week or more until your paddling arms feel like spaghetti.

The rest of the community, particularly those who own beach frontage or run beach resorts, hate cyclones, especially the ones that cross the coast anywhere south of Fraser Island and wreak havoc on beaches and in beachside towns.

Recently-published research, conducted by researchers from the University of the Sunshine Coast’s School of Science and Engineering, and supported by Noosa Council, has bad news for both groups. We can expect fewer cyclones but of greater intensity, and they will form in progressively more southerly waters. But as bad as that may sound, the good news is that the ground-breaking research produced by our local scientists will help predict and prepare for cyclone events with greater knowledge of their patterns and coastal impacts.

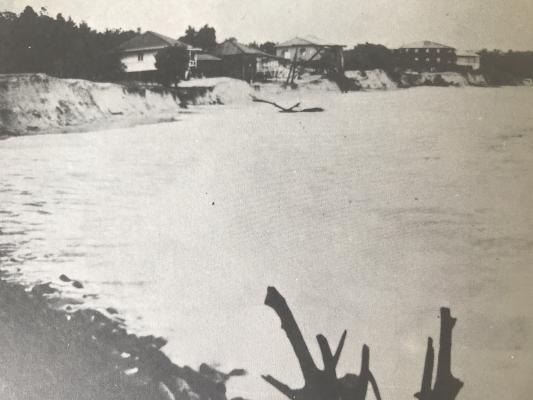

Noosa has a long history of coastal damage from cyclones, with the worst being three consecutive TCs over the summer of 1947-48, which tore the roofs off the Laguna House and Beachhouse guesthouses, blew campers out of the Woods, knocked down the lifesavers’ tower and stole Main Beach.

The 1950s were kinder but Cyclone Dinah in 1967 gutted the beach again (prompting the building of the rock wall) and the eye of Cyclone Daisy passed right over our town in 1972.

As a visiting surfer, I had my first taste of Noosa at the tail end of Dinah, and drove overnight from my job in Canberra to catch Daisy in ’72. In those days we thought Noosa only broke during cyclones, and the locals wisely did nothing to educate us.

After Cyclone David thrashed Main Beach and Hastings Street for more than a week in 1976, Noosa was spared significant cyclone damage until well into the 1990s, when the cycle returned. Now it is changing again.

Authors of “Tropical Cyclone Impacts on Headland Protected Bays”, Daniel Wishaw, Javier Leon, Matthew Barnes and Helen Fairweather, have used this cyclone history to inform their detailed study of the impacts of Tropical Cyclone Oma in early 2019, using state-of-the-art technology to project likely future impacts.

Parts of the report make for alarming reading:

“Future climate projections indicate that erosion and sediment supply issues will be exacerbated in the Noosa region in multiple ways. The expected sea level rise for the region for the year 2100, is between 0.8m and 2m, which is likely to cause widespread coastal erosion of the Noosa beaches. Future projections for the eastern Australia wave climate indicate that Noosa will experience a greater proportion of east to north-east swell and a reduction in south-east swell, which is likely to increase erosion frequency and reduce accretion supply. Projections for tropical cyclone events for north-east Australia indicate a decrease in cyclone frequency, an increase in intensity and more southerly migration of cyclones, with a consequential increase in storm surge and extreme sea-states in the region.”

TC Oma developed in the South Pacific basin near Vanuatu between February 7-15, 2019, reaching peak intensity on February 19 as a Category 3 system. From Vanuatu, Cyclone Oma tracked south-west, passing New Caledonia to the north-west and tracking towards the northern New South Wales coast, before being downgraded to a Category 1 system on the morning of February 22, approximately 800 kilometres east of Noosa. It then turned south-east and continued to lose intensity, before finally turning north as a tropical low.

During Oma, USC’s researchers went to work around the clock. “Not much chance for me to get a surf in,” Dr Javier Leon lamented. Beach volumes were measured using survey-grade drones and GPS equipment. Wave data was collected from two sites operated by the Queensland Government offshore from Brisbane and Mooloolaba. Regional wave and wind conditions were applied using sophisticated SWAN (Simulated Waves Nearshore) computer modelling and relevant tidal information also input.

Fortunately, Oma suddenly changed its track so that the observed and modelled wave conditions showed that Noosa Main Beach was protected from the most energetic conditions. While the Brisbane wave buoy recorded significant wave heights approaching 7 metres, in Laguna Bay, partially sheltered by Noosa Headland, the maximum modelled wave height was 2.1m. “Even so,” says Dr Leon, “maximum water runup was 3.8m above mean-sea-level (2.46 m extra water from the storm) and at 4.5m water would’ve gone over the parking lot and onto Hastings.”

The report notes: “Due to the orientation of Noosa Main Beach, waves required less refraction and were observed to be larger than at Little Cove, with increased wave energy, combined with the strong longshore current, resulted in strong erosion of the beach.”

Dr Leon told Noosa Today: “In the future, with rising sea levels, we should expect even medium intensity cyclones to flood Hastings Street if sediment remains the same. But sediment transport along the east coast is forecast to slow down. What we don’t really know yet is how this will affect Noosa. Daniel Wishaw’s PhD is trying to figure out how that natural sediment headland bypassing is going to evolve in the future.”

The information gathered during Oma, as well as historical comparisons going back to 1958 and computer modelling of the future, have enabled the USC researchers to take giant steps forward in analysing how man-made developments since 1958 have hindered Noosa’s ability to withstand major cyclone events, and what we need to do to protect our town and beaches as sea levels rise and weather patterns change.

But the report concludes somewhat sombrely: “As this beach has the inability to recede, it is likely that future, permanent sea-level rise will result in more frequent and significant erosion events … ”

Read the full and first peer-reviewed scientific publication about Noosa coastal processes at www.mdpi.com/2076-3263/10/5/190/htm#