It’s not every day you get to sell sauerkraut to the Austrians.

Yet that’s what The Fermentier’s Tania Wiemayr-Freeman was doing – figuratively speaking.

Tania and husband Andrew were in Europe as part of the Slow Food Noosa delegation to the 2024 Terra Madre Salone Del Gusto – Slow Food International’s biennial conference and festival in Turin, Italy.

On the way they stopped in Austria, to catch up with Tania’s family who have been involved in fermentation processes for more than three generations.

There she was, not selling sauerkraut to the Europeans but understanding more about it and showcasing the processes undertaken here in Australia – and the added health benefits of that.

As one of the Slow Food Noosa sponsored delegates to attend the international conference and festival in Turin, The Fermentier’s Tania and Andrew were keen to promote the Noosa region and surrounds. They were also there to learn about fermented foods from their fellow delegates at Terra Madre who were representing more than 150 countries.

On the way to the biennial festival and conference, they visited the town of Eferding in Austria, to discover not just family ancestry but a newfound respect for the art of good living – or living well – as part of Slow Travel.

Eferding is the third-oldest town in Austria, and also home to the country’s largest sauerkraut manufacturing factory.

“After World War Two, Austria was chaotic,’’ Tania said. “There was anarchy until a government was formed.

“The farmers got together and formed a co-op, and part of it was to process their own goods – sauerkraut and gherkins were a staple so they were good at it.

“In Austria they generally cook it now whereas we like to promote eating it raw – as opposed to pasteurising it to kill all the organisms.

“We know it can be made safely and to eat it raw is of more benefit. We want those bacteria in there.’’

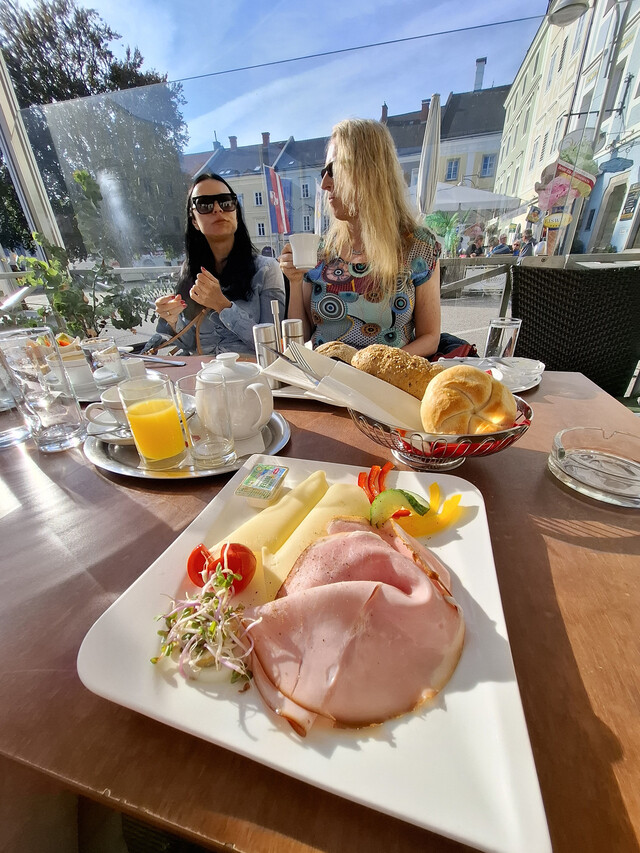

Tania said the towns of Austria had that smell of smoked and dried meats from the butcher, and of the fresh bread baking in the morning.

Her father’s home town was the Mill Quarter (Muhlviertel) – that was a flax-growing area for making linen – and he learnt the trade of weaving.

The farm has been in the family for 400 years and the house had the animals in the bottom storey to help keep them warm in winter.

“You still hear the ’cling’ of bells when you open the doors of shops. The drying racks of meats and salamis when you walk in.

“All those cold meats and sausages … it’s a memorable smell.

“The people would go there for a snack. A heavy bread roll and inside is a type of meatloaf … absolutely delicious.

“We would always have it hot. Warm bread and warm meat, with mustard perhaps.’’

It was such a coincidence for Tania – living in Australia, the daughter of an Austrian migrant who came from the same city as Austria’s largest sauerkraut manufacturing factory.

Now, while born and bred Down Under, Tania has been producing sauerkraut and going back to her father’s home town.

Her grandfather bettered himself by buying a business in the town … with a walled centre, moat and fortress on the hill.

The market square has shops around it -the baker, the butcher and the family hotel.

Her father had gone into brewing as a side business to farming, which sees Tania’s auntie and cousin still living there.

As a dietitian on the Sunshine Coast, Tania was telling the farm co-operative staff to better promote the health benefits of sauerkraut.

“Where is the food tourism aspect?’’ she asked. “The whole of Austria knows about your factory – tap into the food tourism, cooking and health benefits.’’

The family visit saw swapped tastings of each other’s creations, and they were particularly impressed by Tania’s turmeric in sauerkraut.

The co-op manager knew Tania’s family, as did the local policeman.

“Gemutlich is a word that describes the feeling well – it means homely, comfortable, sharing, convivial.

“Sure enough, they gave us a stack of samples … that were served as traditional dishes in the policeman’s private house.

“The policeman’s daughter came and helped us at The Fermentier while she was travelling prior to starting university.’’

What Tania learned from the visit was family can be so connected and this gave a sense of belonging.

“Knowing who they are is something you cannot buy – knowing your neighbours, the local shops. It’s just terrific. I love it.’’

From a Slow Food perspective, as a delegate to Terra Madre (Mother Earth) it heightened our awareness of the increasing problem with food sovereignty in Australia.

“This was highlighted again during Cyclone Alfred with the interruption to food supplies.

“Councils have to take better control of town planning and protect farm lands.

“There needs to be limits to where we can build houses so the fertile farmland is protected.

“Europe provided a really strong impression … this is what we need for food continuity.

“They have been through so much and understand the need to protect it. There is a place for subsistence farms, not just monocultures.’’

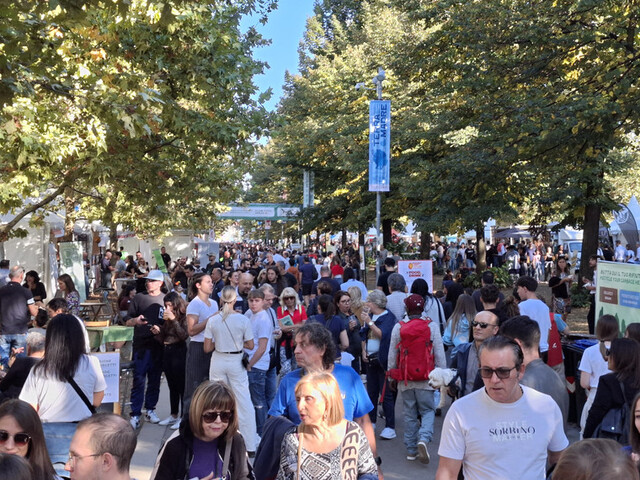

Terra Madre was a real eye-opener for Tania and Andrew – to be part of a food event that attracts 500,000 over five days.

After connecting with other Australian delegates it was good to sit back and see the festival site from a modern viewpoint – what was a heavily industrialised area is now re-purposed as parkland and for events.

“The old factory frameworks were a great backdrop to the venue.

“It was exciting to be part of it … to see the other countries involved, some in national costume.

“Being from Australia we couldn’t bring produce to sell or sample due to quarantine issues, but our fellow delegates had bush tucker … lemon myrtle, pepper berry, lemon verbena and the like.

“Slow food is the best food and the gourmands are looking for flavour. They were intrigued by the aromas.’’

Slow Food Noosa delegates gave presentations about the region.

The way the delegates were received saw them invited to visit the University of Gastronomic Sciences outside of Turin.

“This was an awakening for me … about the joy of eating and experiencing good food.

“The visit broadened my appreciation and highlighted the importance of good food knowledge. If you can help people enjoy their food, particularly with dietary restrictions, they’re more likely to keep with them and enjoy them .

“It’s not about restricting foods. You can have a small amount of something delicious which just transforms the meal.

“You might be restricted in salt but one little olive added to a whole salad can make a huge difference.

“There’s a lot of learning for dietitians and nutritionists from the gastronomic side – and that is the heart of Slow Food. It is promoting the science of gastronomy to improve people’s lives.’’

That was the key for Tania – having experienced the world‘s first university of gastronomic sciences.

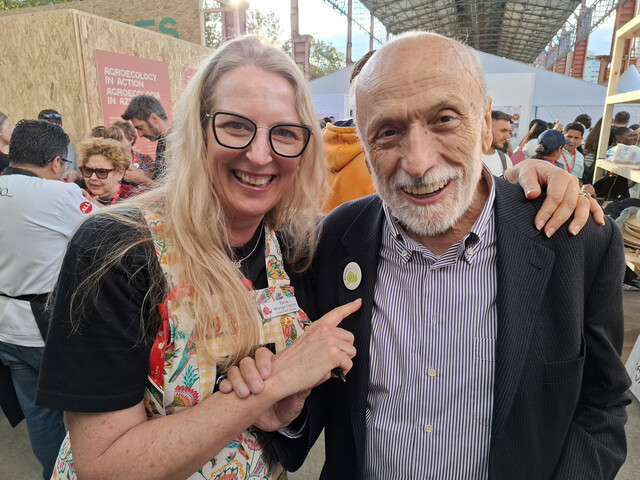

Slow Food Noosa has now started to make connections with the university, which was started by Carlo Petrini.

Petrini was the founder of Slow Food in 1986 in Rome, in order to elevate the public perception of gastronome and chefs as in his book, Slow Food Nation, he talks about how they’ve been sidelined.

In the scientific community or the academic world of universities, knowledge about food is broken up into food science, food technology, dietetics and then it stops, Tania said.

“Nothing brings it all together around food appreciation – the scientists get all the accolades while the dietitians and chefs haven’t had an avenue for that learning.

“We were welcomed with open arms and shown around the whole university. There are public tours all the time so we went into its wine BiblioTech, which is a word for library.

“Farmers and vintners bring wines from every season which are catalogued and kept there with every batch. They have to bring a sample of the soil and put it in a glass jar so now with DNA sequencing who can imagine how much knowledge they can learn about the terroir – the land in which the wine is produced – which contributes to good wines.’’

Andrew went to the market at Bra, the closest proper village or town to the university, and the open market is in the middle of the town

“There is unbelievably fresh produce – and those people know food,’’ Andrew said. “It was a matter of what fish do you want?

“Do you know when was it caught? Have a look at the eyes.’’

Talking about the Italian food, Tania said there were so many vignettes .

Walking around the kilometres of food stalls at Terra Madre meant many free samples.

“What stands out was all of these people going to a stall and they were coming away from it with big, long bamboo skewers – like one that we would use for a kebab – and there were round white balls on it.

“Being Australian, I assumed it must’ve been marshmallows because deep-fried things would’ve looked yellow or brownish. Yet these were bright white, so I thought marshmallows.

“How wrong I was. We waited in line and asked people what it was. They were buffalo mozzarella balls!

“It must’ve been the best because I can tell you people flocked to that stall and it just highlights how they eat so healthily.

“They choose different foods because they’ve developed their taste buds. They’ve developed the appreciation of food and they’ve grown up with it.’’

One of the stands had more than 100 different varieties of tomatoes because part of Slow Food’s philosophy is maintaining biodiversity and heritage seeds.

This is at a time when single-crop farming could see the world faced with only a handful of varieties.

That was fascinating to see, but also the kombucha tasting at the South Korean stand.

“The dried meats just melted in your mouth, and the taste of gorgonzola cheese … oh, my goodness. It was like heaven.

“They talk about a bliss-point in gastronomy and in food science – a good example is Lindt chocolate. It totally gives us the happy hormones in our brain.

“It was exactly the same with this soft, white cheese. They had a champagne flavoured one, a truffle flavoured one and the plain one.

“It was the same with the anchovies – I had never tasted one this good.’’

The Slow Food Noosa Snail Kids presentation of connecting farmers and their produce with school children was an outstanding success on the world stage.

Slow Food Noosa is at the cutting edge with the education committee and have contributed to their white paper on it.

One of the things Tania and the Noosa delegation did was show how to make sauerkraut by doing the actions to a song prepared for school children.

People were fascinated and started joining in – particularly the Japanese contingent.

As a result, a Snail Kids presentation was made at a primary school and kindergarten in Turin where the students got to show their gardens and projects.

At Terra Madre, Tania and Andrew met a person from the Italian Alps who made sauerkraut and while they have similarities in their cuisine it was unusual to find a maker in Italy.

“We were excited to find a farmer who grew the cabbages and made the sauerkraut. We had a tasting with olive oil to make it like a salad.

“Like much of Italy – and Europe – the cabbages were particular to his area.

“They were a type that I’d never seen before. They were small and flat.

“They weren’t for sale but he gave one to us as a gift – they were very dense-headed and that contributed to the flavour of sauerkraut.

“That was a beautiful exchange. We really wanted to give him a taste of our produce.’’

That moment was so representative of how proud Tania and Andrew were to be part of this diverse global food movement.

Part of Tania’s sharing of knowledge has been to provide dietitian support for the National Referral Hospital in the Solomon Islands – both for the Nutrition Department and within the PRIDA (Pacific Region Infectious Diseases Association) network.

That has included a visit funded by the University of The Sunshine Coast, and Tania continues to provide support remotely.

At the opening ceremony of 2024 Terra Madre, Carlo Petrini reminded that now is the time to restore the value of food.

For Tania and Andrew, their journey was filled with joy and reunions, together with a strong sense of community and unity.

It was a reminder that, whether as producers or consumers, we are in this fight for good, clean, and fair food together.

However, it has also highlighted the challenges small family-run businesses can face in the development then marketing of their produce.

It was also a reminder of the importance of family.

This has led to Andrew and Tania’s decision to close The Fermentier and concentrate on supporting their children as they make their way in some exciting endeavours in the food industry.

It will also allow Tania to pursue further studies and presentations in nutrition, gastronomy and sustainability.

Through their travels and journey with Slow Food, Andrew and Tania have not only re-connected with their families but developed lifelong friendships through their work, and will provide a wealth of knowledge to good food, and the better health of everyone that their contributions touch.