Actually, we have plenty, but virtually none of them are grown locally.

This wasn’t always the case.

In fact, this month we celebrate what is almost certainly Noosa’s least-known centenary.

It’s 100 years since we became the top banana in Queensland’s banana industry, providing more than 25 per cent of the crop for the first time.

How did we do this?

Well, with a lot of help from something called banana bunchy top virus (BBTV) which had decimated Australia’s biggest growing region, the Tweed Valley in NSW, plus some other luck factors we’ll get to in a moment, but the fact remains that in the post-war years from 1918 to 1922, Noosa Shire (with a little bit of help from parts of Gympie and Widgee) grew its share of a growing Queensland production level from 12.9 per cent to 25.6 per cent.

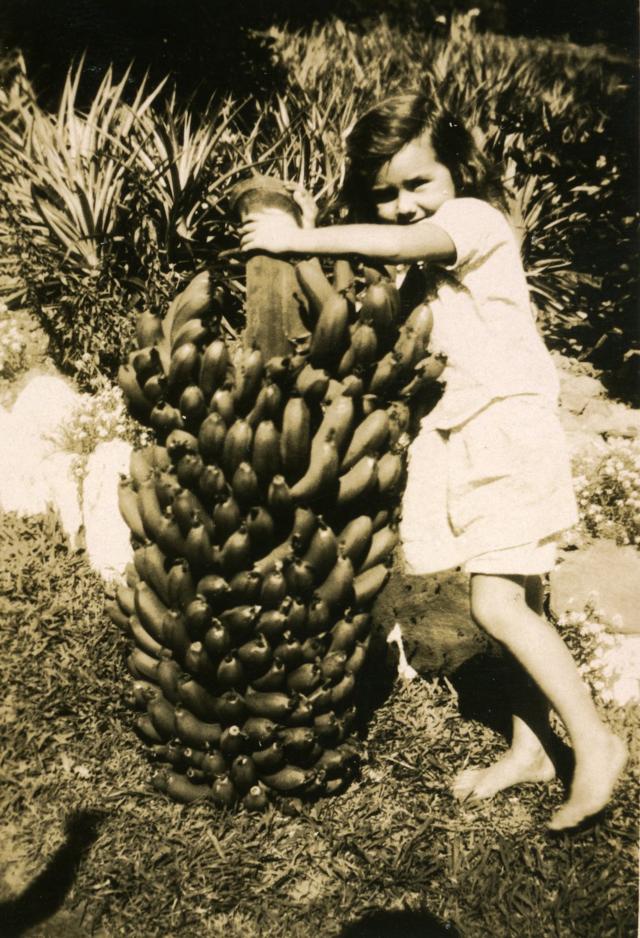

Over the same period Noosa banana production increased by an amazing 340 per cent, from 163,000 bunches to 554,000.

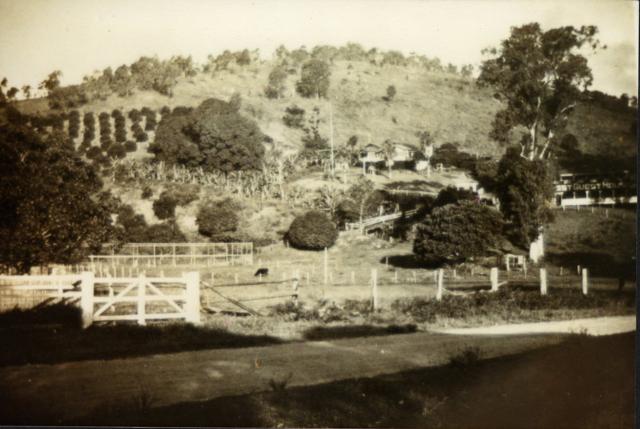

The banana boom ended almost as quickly as it had begun, but it provided an economic stimulus just when the shire needed it, and the remnants of those glory days could be seen right in the heart of Noosa not so long ago, with the Freeman family plantation, Noosa Vale (cleared for bananas in 1929), above Halse Lodge on Noosa Hill, and Hack’s banana farm (cleared 1943) just around the ridge where Viridian Noosa is today.

The population of Noosa Shire almost doubled between 1921 and 1927 (from 2387 to 4413), and grew another 30 per cent between 1927 and 1933.

Much of this growth was due to Queensland Government rural settlement incentives and a major federal program of soldier resettlement following World War I.

While many of the new settlers took up dairy farming, an increasing number combined their small herds with crops, particularly bananas.

Bananas were first grown in the Noosa region in 1908 at Goomboorian near Gympie, and from about 1913, at Maroonda Experimental Farm at Amamoor in the Mary Valley.

In 1916, the Gympie and District Fruitgrowers Association was formed, and in 1921 a fast fruit train service was extended to Gympie.

Growers were able to prosper quickly, using as little as five acres of fertile soil, so start-ups required very little capital and the crop quickly became a lucrative sideline.

A bonus from this was that the struggling timber industry suddenly had a new product line. Banana case mills sprang up all over the shire, often very basic affairs erected on leasehold farms where there was a suitable stand of softwood timber, but the big mills also tooled up for case production.

And when Tweed bananas went pear-shaped, Noosa really stepped up to the plate.

Kin Kin, already a first prize winner at Gympie and Brisbane shows in 1917, led the way.

At the time of the honour, the Noosa Advocate reported that, while Kin Kin had been previously acknowledged as a first-rate dairying district, it was “now known to have thousands of acres of the best banana land in Australia”.

Cooroy soon followed the Kin Kin lead, and by the early 1920s, the north-western part of the shire was dotted with plantations, packing sheds and the settlements of the various migrant groups who came to work the crops, among them Chinese, Indian and Sri Lankan (the biggest of the groups).

Old Ceylon Road in West Cooroy is named for the 500 or more Sinhalese Buddhists who lived and worked on its plantations during the post-war years.

During 1926, nearly 15,000 cases of bananas were freighted from Pomona Railway Station alone, an increase of 50 per cent over the previous year.

The Queensland banana industry, half of it within Noosa Shire, was estimated that year to be worth more than £1 million to the state economy.

But the boom proved to be short-lived.

By 1932 the 25.6 per cent share was down to 22.3 per cent. It continued to decline and all but disappeared in the mid-1930s.

The main reason for the decline was the return of the Tweed Valley as Australia’s banana basin, but by the time the Noosa agriculture sector realised it had a problem, an even bigger one was upon them — the Great Depression.

Today the tropical banana-growing regions of northern Queensland, mainly around Tully and Innisfail, produce more than 90 per cent of Australia’s bananas.

Other tropical production areas in the Northern Territory and in northern Western Australia, at Kununurra, account for most of the rest, although subtropical bananas are still grown from just south of Coffs Harbour, NSW to Bundaberg.

So we’re no longer top banana, but every fresh banana you eat is Australian home-grown, even though the fruit came from China, introduced by Chinese workers on the goldfields 150 years ago.

On the strength of that, I’m blending another banana daquiri.

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win tickets to the Queensland Ballet at The J Theatre](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Queensland-Ballet-100x70.png)