“Working out how to tell stories was a bit like finding my soul,” Bryan Brown tells his audience.

“Does that sound too wanky?”

Wild applause. The audience doesn’t think so, and we’re away on a fabulous hour of self-deprecating humour, mild obscenity, easy-going storytelling and some profound insights into the art and craft of bringing Australian culture to life on stage, screen and printed page.

David Williamson and Bryan Brown are both iconic figures in the past half-century of Australian storytelling, their vast bodies of work shining an entertaining and often telling light on the Australian psyche. Either of them could be in the spotlight tonight and the audience would be just as thrilled, but Dave, having enjoyed a wave of recent accolades since turning 80 in the not too distant past, and having made the first tentative steps towards becoming Australia’s greatest living former playwright, he’s happy to ask the questions and let Bryan bask in the love.

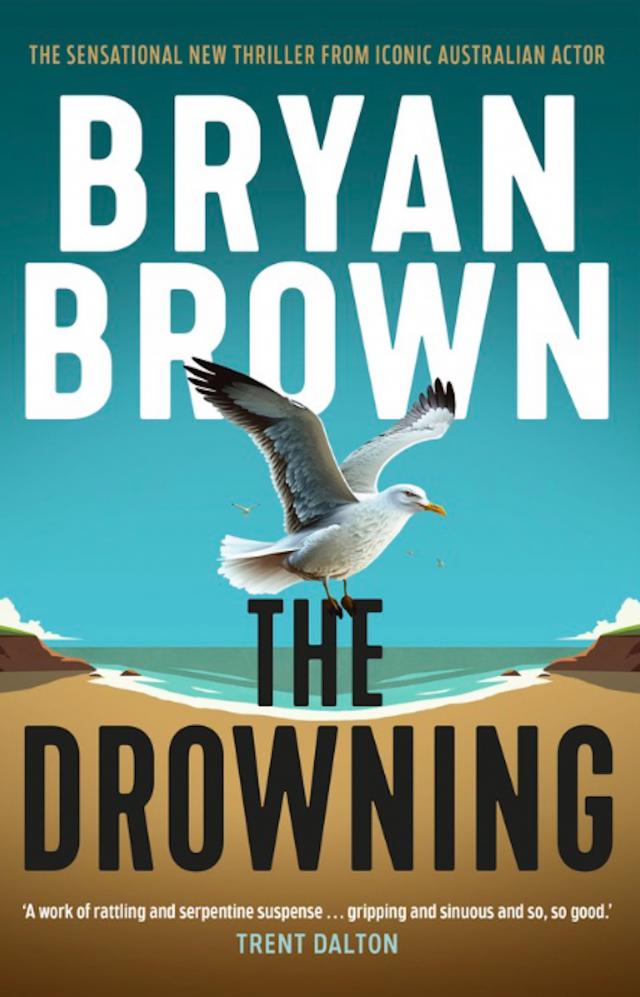

It is, after all, the occasion of the Noosa launch of his first novel, The Drowning, a ridiculously fast-paced page turner that skilfully twists its way around a central plot involving murder, drugs, liaisons and lies, all set in coastal town in northern NSW, not completely unlike the place where Bryan and wife Rachel Ward have a hideaway.

He says: “I can’t name it because in the book there’s a bit of who’s doing what to who and who’s paying, and I worry that no one in that town will speak to me again.

“So I won’t name the town, but we all know it because there’s a whole bunch of them along the coast and we also know the characters that frequent them. So the scene is full of colour and interest and richness and tension and drama, just like it probably is here in this lovely town [Noosa] where we’ve all gathered to listen to us bullshit on. Every place has its underbelly, and it’s great to be able to explore that.”

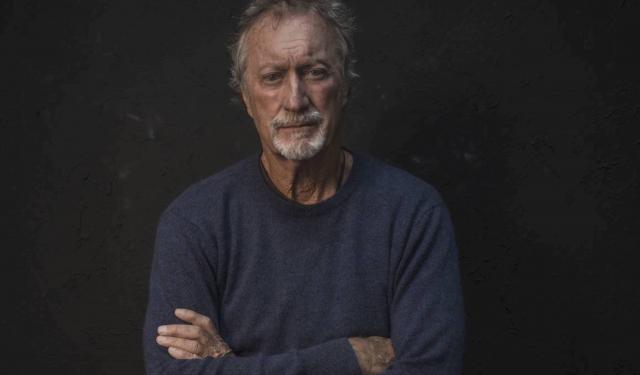

Still lean and lantern-jawed in his middle 70s, Bryan comes across as a rough diamond of a bloke who’d mop up the floor with you if you did the wrong thing. I have some slight experience of this. Forty years ago he pushed me across a restaurant with a firm finger prodding my chest and a wave of suggested anatomical impossibilities gushing from his mouth, all over a perceived slur I’d written in a local paper.

But the beauty of Bryan is he gets it off his chest and can laugh about it minutes and decades later. Quick to anger, quick to forgive. It was probably ever thus.

Bryan says: “I grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney where my mother was a single parent bringing up two children after my father had pissed off early on. Mum had no family of her own but she was this wonderful woman whose devotion to my sister and me gave us a life of opportunity for which we’re both eternally grateful. Mum cleaned houses and played the piano at ballet classes. In fact every Saturday after I finished playing football I’d have to wait around at ballet for mum to finish, so I knew how to do the plie and releve before I knew how to pack down in a scrum.”

Such cultural beginnings obviously rubbed off but the arts were not his first calling.

“I loved school and remember being pissed off when it finished, thinking, I’m never going to get a better lurk than this. Sport, mates, four months off a year, what can beat that? So I didn’t really have an ambition, which might be partly because there was never a father in the house.

“But when I left school someone who knew I was good at maths suggested I become an actuary, so I studied for that, joined the AMP Society.

“In those days if you went to work for a big company you’d probably be there for 40 years, so they had a social responsibility to you and they had clubs. The AMP Society had a drama club and they produced an end of year revue, a show where they sent up the bosses and so on.

“A notice went out that auditions would be held that afternoon so I went, thinking that there’d be plenty of girls. I read some lines and they asked me to join and told me to come to rehearsals at 4.30 the next afternoon.

“I was a good worker and I liked going to work, but I’d never woken up on a morning when I just couldn’t wait to get there, knowing that at the end of that day I was going to do this thing called rehearsal, not having a clue what it was. I soon found out and I loved it and wanted to learn more so I joined an amateur theatre company.

“After a few years I thought this was a good lurk so I sold my car and went off to England.”

Bryan spent the first half of the ’70s treading the boards in London, including some minor roles with the Old Vic, before returning to Sydney where he made his two-line screen debut playing a cop in Scobie Malone. By the end of the decade, however, he had worked with many of the emerging greats of Australian cinema, and his 1980 lead role in Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant made him a world star who has now appeared in more than 80 films and TV shows and worked in 20 countries. In 2021 he published his first book, the best-selling short story collection, Sweet Jimmy.

He recalls: “When the book did alright, once the publishers knew they could make a quid out of me, they were on my back saying when’s the next one? Why don’t you write a novel?

“Quite truthfully, I didn’t think I was capable of writing a novel. I mean writing was a new source of enjoyment for me, but it wasn’t meant to go anywhere. But once I got this little thing going in my head – they want a novel, I can’t write a novel, wait a minute, maybe I can – it started to take root.

“At our north coast property we often take off up little back tracks that lead to houses where there’ll be a sign saying DO NOT ENTER. So I was driving along one day thinking about those tracks and those signs and what they might mean if you’re a young bloke of 16 or 17. It’s like a magnet. I thought, I’ve got a start here, and I’ve got a character.”

David Williamson: “I love the way you use language. You don’t waste words and you pick the right ones to use time after time. And you get on with the story. I read literary fiction where after a lot of pages I find myself screaming, get on with the story! You don’t hesitate.”

Bryan: “My book is about 280 pages long. It could be 500 pages but I took out all the adjectives and adverbs. [Laughter] In our game of film-making I get to spend a lot of time with writers, particularly if I’m producing.

“We’ll buy a book, bring a screenwriter in and start to work. Or if I have an original idea we’ll hire a scriptwriter to come and work with me. In both cases the important thing is keep the story going. Too often, you’ll start out enjoying a movie or a series and then you’ll reach a saggy area where the story doesn’t go on, it’s just treading water. That’s where the thing we’ve learnt over so many years in this business comes in: keep the story moving!”

He certainly does that.

The Drowning (Allen & Unwin, $32.99) is a well-crafted cracker of a book, available at all good book stores.