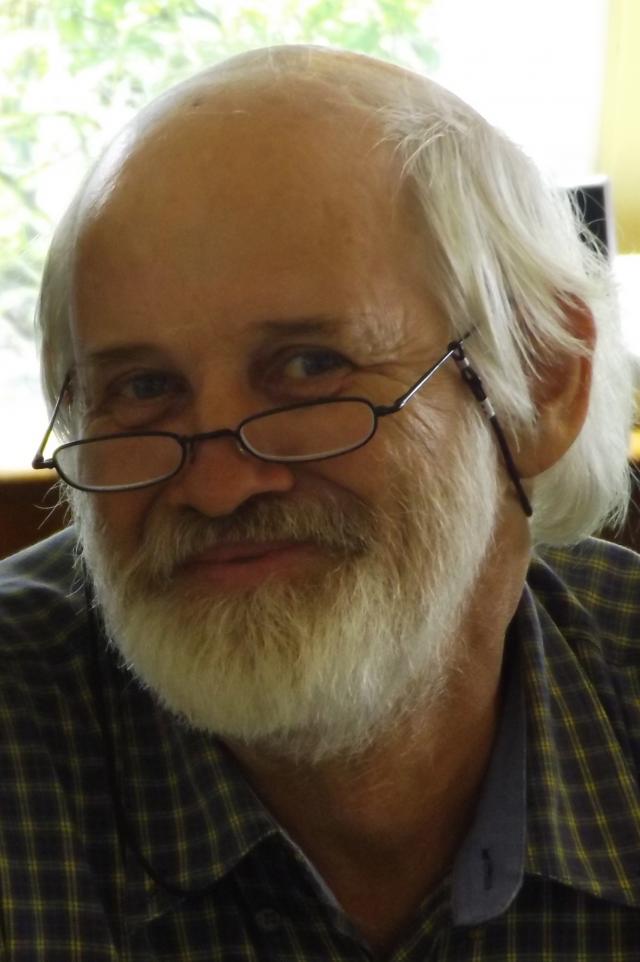

Ian Mackay, Noosa’s favourite bush poet and Mary Valley environmental warrior, is not happy, Jan.

In fact, he tells Noosa Today from his Kenilworth property: “I’m really hot under the collar! And the reason is public vandalism – death by the chop of a number of recently planted bunya trees, part of an avenue on the Eumundi approach to Kenilworth.”

According to Ian, the Sunshine Coast Council planted the avenue of bunyas a couple of months ago in good faith in recognition of the importance of the bunya in local Aboriginal history, but failed to consult “influential locals”. An article in the Mary Valley Voice newspaper in March brought the disgruntlement of the few to more general attention, but blamed not the lack of consultation but rather the fact that bunyas drop prickles and cones at certain times of the year.

Says Ian: “This objection is truly lame, as anyone walking alongside a well-used road is ill-advised to be doing so in bare feet. All those who have picked up roadside litter on Clean-Up Australia Day will tell of broken glass, tin cans and more, lurking in the grass, often rendered even more dangerous by having been run over by the slasher or mower. Even an innocent hubcap after a couple of passes with the mower can become a lethal weapon.

“The wider world plainly does not share this paranoia for prickles. In pride of place in Queen’s Park in Maryborough, for example, is a large bunya tree reputed to have been planted by John Carne Bidwill after whom the plant was named. Presumably Maryborough residents and tourists have the sense to wear shoes and to avoid walking under the truly majestic tree when the cones are falling. There are a number of bunya trees happily resident in the old botanical gardens in Brisbane too, and some at Government House, and a wonderful example in the grounds of Mapleton school. So no, prickles in feet and falling nuts are not valid reasons for the removal of the bunya avenue approach to Kenilworth.”

A new dimension entered the Kenilworth bunya war on the night of 3 April when eight of the newly-planted saplings were ripped out of the ground. “They got the posse up under cover of darkness,” says a disgusted Ian Mackay. “Bunyas to me aren’t just a tree with prickles and cones, I respect their enormous significance to our First Nations people who were here long before the residents protesting the planting. Hinkabooma (Kenilworth) was the heart of bunya country, and this avenue planting is more than a nod to that enormous respect in which bunyas were held.”

At the very start of European settlement, bunya trees were in abundance in south-east Queensland. Andrew Petrie, Commissioner for Works in the Moreton Bay settlement and a prolific explorer was the first to bring back samples of the bunya and the first to recognise its significance to First Nations people. Bunya gatherings, both at Baroon Pocket and what is now called the Bunya Mountains, drew up to 5000 attendees, many travelling long distances to be there for the feasts, corroborees, trading and sharing of food, as well as arranging marriages and resolving issues of law. Former Noosa Library historian in residence Dr Ray Kerkove has written: “The Bunya Gathering was arguably the largest and most influential Indigenous gathering in Australia.”

Andrew Petrie’s representations to Governor Gipps in Sydney (Queensland being still part of NSW at the time) of the significance of the bunya trees and the bunya gatherings, led to the Bunya Proclamation of 1842, which stated in part: “His Excellency is pleased to direct that no Licences be granted for the occupation of any Lands within the said District in which the Bunya Tree is found. And notice is hereby given, that the several Crown Commissioners in the New England and Moreton Bay Districts have been instructed to remove any person who may be in an unauthorised occupation of Land whereon the said Bunya Trees are to be found. His Excellency has also directed that no Licences to cut Timber be granted within the said Districts.”

The Bunya Proclamation should have meant that bunya country would remain a sizeable reserve for First Nations people, but settlers eyed off the land and timber–getters eyed off the trees and thumbed their noses at the Bunya Proclamation, and by 1850 they had begun taking up land on bunya country around Kenilworth. And when Queensland became an independent colony in 1859, the proclamation was repealed.

As Ian Mackay notes: “Gipps was regarded as an enlightened governor but he more than ruffled the squattocracy, nowhere more so than in his policy towards Aborigines, which was humane, practical, and courageous.”

None of which helps the eight little bunyas who have moved on to the spirit world, but Sunshine Coast Council has pledged to replace them and continue with the avenue of bunyas concept.