Not quite two years ago former Noosa mayor Tony Wellington unleashed the next phase of his storied career with the launch of a book with a premise so simple that it had authors all over the country whining, why didn’t I think of that!

Freak Out – how a musical revolution rocked the world in the Sixties, stormed up the charts as you would expect of the whimsical Wellington’s fascinating take on all of the old songs that we early stage baby boomers love to sing in the shower, to such an extent that his publisher was soon calling for an encore.

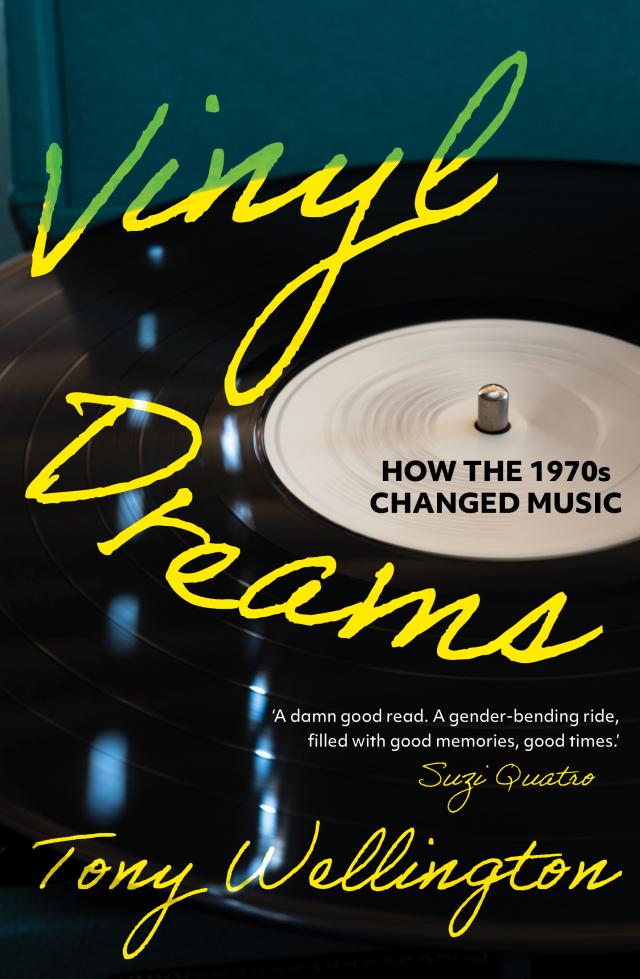

And here it is in Vinyl Dreams – how the 1970s changed music, described by none less than rock legend Suzi Quatro as “a gender-bending ride, filled with good memories, good times”.

Vinyl Dreams will be launched at Noosa Arts Theatre on Friday 9 June from 6pm, with virtuoso drummer Duncan McQueen demonstrating the rhythmic moods of ‘70s music.

Chronologically presented, Vinyl Dreams is a great reference book for rock tragics, but it’s also a wonderful read that I can’t put down, aided by the author’s audio innovation of a Spotify playlist of almost every song discussed. So it’s read/listen/pause/repeat. Perfect!

Tony and I sat down on a balmy autumn afternoon to shoot the breeze about the music that made our generation.

NT: Your playlist accompanying Vinyl Dreams is 55 hours and 20 minutes long!

TW: And that’s just an edited selection.

NT: What was the process – you finished the book and then went through every song you mentioned and chose from that?

TW: Well, once we’d done the first edit I just went through the book and picked the eyes out of it for the songs I’d referenced that I thought people might want to listen to. This came about because my wife Judy was reading an early draft in our lounge room and I noticed that she would stop every so often, hit Rhapsody and play a song that she’d just read about. It dawned on me that we could make that easy for readers so they don’t have to go hunting.

NT: I’ve been listening to it on Spotify and loving it, but surely all these songs weren’t already there, were they?

TW: Yes, they were all there, the only problem being that Neil Young and Joni Mitchell have withdrawn most of their own albums, which was a stumbling block, but still there’s plenty to listen to and it covers a lot of territory.

NT: In your prelude you say that the first song in the playlist, Surrender Rose by Don Cherry, made you “swoon”. I’d never heard of Don Cherry and I’m not given to swooning, but me too! So great start. Like you, having lived the ‘70s listening to a lot of diverse music, I’m surprised by how many tracks were new to me, which, alongside the old favourites, makes the experience of listening while you read so interesting. But I can’t agree that the Carpenters’ Close To You “sends shivers up my spine”, at least not in a good way.

TW: (Laughs). Well, that’s the wonderful thing about music. You don’t have to agree.

NT: I’d forgotten about Gil Scott-Heron too, and fell in love with Whitey on the Moon all over again.

TW: Isn’t it fabulous! And it’s great to remind people that rap music had its beginnings back then with Scott-Heron and then the Watts Prophets and the Last Poets, that notion of putting music with poetry, which came out of the Beat Generation a long time before rap and hip-hop.

NT: I could sit here and talk all afternoon about the playlist, but we’d better get onto the book. How the hell did you get Suzi Quatro to read it, let along give you a rave blurb?

TW: The publicist for my publisher had a connection with her and was able to arrange it. The other blurbs I arranged.

NT: Yeah, but nice as they are, they’re the low hanging fruit. Suzi Q is serious.

TW: Yes, it was a bit of a coup.

NT: In his blurb, former Powderfinger drummer Jon Coghill says he loves the way you “humanised” rock stars. Now I’m guessing you don’t know that many of those you write about, not even Suzi Quatro as it turns out, so how did you do that?

TW: I guess by not writing a hagiography, which most rock biographies tend to be, gushing and sycophantic, and that was not what I was interested in. But I read a lot of biographies and autobiographies, and endless interviews and articles to piece together what was going on behind the scenes, as well as with the music, to try to give people a feel for it in terms of the sociopolitical focus of the times. The autobiographies often tend to be mainly about self-justification, although Steven Tyler, to give him credit, admits to getting custody of an under-age girl so that he could take her across state lines when Aerosmith was touring. Rod Stewart was quite open about the fact that as an adult he drew penises on hotel walls. These were not mature people. I think it was part of the rebellious nature of rock, and they wanted to be seen as social rebels.

NT: But a lot of what you describe goes beyond that, to shocking sexual abuses, for example.

TW: Oh, with bands like Led Zeppelin it was quite horrendous.

NT: Did your extensive research turn you off any of your rock heroes?

TW: Mmm, good question. Discovering what some of them did was an eye-opener for sure, and it made me separate the music from the person to some extent, which we do in the arts world all the time. Gauguin was a pedophile but he was also a great artist. I love the music of Frank Zappa but I don’t like his attitude to women. But it is a dilemma because the true nature of the artist feeds into their work, so when you learn about their true nature you also discover a lot about the subtext of their work. Eric Clapton is probably a classic example – a pugnacious, racist, far right piece of work and a hell of a good guitar player. I think the problem for the rock stars was that they had too much too soon. Many of them achieved not only notoriety but enormous incomes before they knew how to handle it. In a way it infantilised them because they didn’t have to struggle for anything and they were surrounded by sycophants. But I wasn’t a music fan who hero-worshipped. I didn’t have posters of rock gods on my bedroom walls, so perhaps I always came at music from a more cognitive level. In the ‘70s I was much more interested in electronica, avant garde and jazz fusion than I was in Top 40, but I was still acutely aware of the more popular stream.

NT: That’s an interesting point. My favourite music of the ‘70s mostly came from the first half, when you had the singer/songwriters emerging, while the second half was all about punk and disco, but you seem to embrace it all.

TW: I guess you could say I’m fairly catholic about music genres because I think they all have credibility and purpose, and while I wouldn’t put a punk album on to listen to while doing the washing up, I have enormous appreciation for how they responded to the times. So I hope that I’m pretty even-handed but I think it’s quite clear to the reader what I’m passionate about, what I think are the highlights and who are the groundbreaking artists of the era.

NT: I’ve read a lot of rock biographies but only four live on my bookshelves still – Dylan’s Chronicles, Springsteen’s Born To Run, Keith Richards’ Life and Paul Kelly’s How To Make Gravy. What’s the best and worst on your list?

TW: Chrissie Hynde’s Reckless was one of the best, a wonderful book, brazenly honest, candid and it doesn’t feel like it’s been written by a ghostwriter, as most of them have of course. The worst is a long list, but Debbie Harry’s Face It, which drips with narcissism, would be on it.

NT: Did you buy all those rubbish books?

TW: I did a lot of scrounging in secondhand shops because many of them are out of print. That was part of the joy of doing the research because I love secondhand bookshops. Some of the gems I picked up that way were beautiful compilations by music scribes of the era like Robert Christgau.

NT: Having written two comprehensive music histories now, you must have worked out a process. What comes first, song, artist, genre or context?

TW: I do an awful lot of reading and an awful lot of listening and then I basically write chronologically. In this case I had the theme and the spine in my mind so I just gave myself a number of weeks on each year of the decade. That made it more manageable.

NT: But it’s still a vast canvas to cover. The year 1970, for example, is more than 70 pages!

TW: Yes, ’70 and ’71 are the longest chapters because there was so much happening, particularly in terms of the explosion of music as a result of not just technology but an embrace of the new. In the UK and Europe you had progressive music borrowing from the classics while in the US you had fusion borrowing from jazz, and right through the middle you had an explosion of heavy metal thanks to Black Sabbath and everyone who came after.

In part two of Vinyl Dreaming next week, stadiums rock as the decibels get turned up, and Oz rock lights up. Tony’s book launch at Noosa Arts Theatre is a free event but registration with Annie’s Books would be appreciated. 5448 2053 or info@anniesbooks.com.au