It’s hard to believe today that Aboriginals in Queensland would apply to the state government to become non-Aboriginal but between 1908 and 1965 more than 4000 did.

Aunty Judi Wickes had never heard of Queensland Aboriginals being awarded a Certificate of Exemption until she discovered one in her grandfather’s possessions after he passed away.

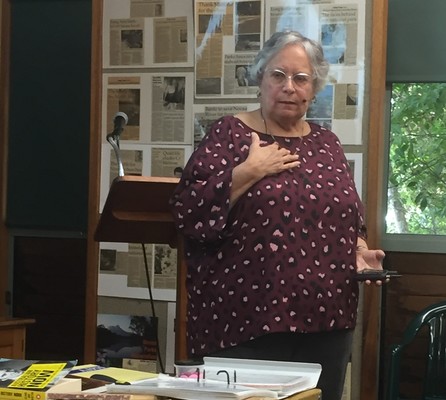

The finding set her on a path of research that she discussed at last Friday’s forum at Noosa Parks Association and which will lead in October to the first symposium on the Certificate of Exemption.

A Sunshine Coast Elder and a Kalkadoon and Wakka Wakka woman, Aunty Judi said The Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 gave the Queensland Government controls over all aspects of the lives of Aboriginals including where they lived, worked, their wages, who they married and, in some cases, whether they could keep their children, until it was repealed in 1965.

Aunty Judi told the group her grandfather Roy Smith was taken to Purga mission, near Ipswich, when he was 13 years old in 1914. Her grandmother, Daisy Power, was sent in 1920 to Purga mission when she was aged 19 years. Both had European fathers. Aunty Judi said up to the 1960s children of mixed descent were taken and placed in government institutions “for their own protection”.

She said the boys were taught to work on farms and the girls were sent out as domestic servants.

Not happy with his treatment and the conditions Roy Smith in 1920 applied to the government for a Certificate of Exemption. It was granted six years later. Aunty Judi said only “half-caste” Aboriginals were allowed to apply for the certificate until 1939 when it was open to all Aboriginals.

“People who got an exemption lived in mainstream society and became a non-Aboriginal person,” she said.

“They weren’t allowed to mix with Aboriginal people.”

Roy was by then married to Daisy and they had a child. As Daisy was married to a non-Aboriginal she also became non-Aboriginal.

Aunty Judi said although the exemption afforded them some privileges it meant they could no longer have contact with their Aboriginal families or friends. They remained under surveillance and lived with the threat of the exemption being revoked, she said.

“My mother told me her father said you can’t do anything wrong or the government will take you away,” she said.

Aunty Judi said finding out about the Certificate of Exemption went some way to explaining why her family lived largely in isolation and had lost contact with family.

A symposium titled Rethinking and Researching 20th Century Aboriginal Exemption will be held in October at La Trobe University in Victoria.