Dave Burrows’ personality and his incredible knowledge of the land drives the [Land For Wildlife] program. – Cr Tom Wegener

Dave is a softly-spoken man of action. He gets things done and he’s never afraid to get his hands dirty. His love for this shire and his efforts for it deserve to be recognised. – John Charlton, co-owner Mas Montserrat, Cootharaba.

He is my hero. I’d do anything for him. – Montserrat Martinez, co-owner Mas Montserrat, Cootharaba.

It would be a long day’s walk through rough country to try and find anyone with a bad word to say about Noosa Council’s conservation partnerships officer Dave Burrows, and even then I don’t like your chances.

The quiet man who has led council’s involvement in the Land For Wildlife program and negotiated Voluntary Conservation Agreements with landowners since their inception seems to have an intimate personal relationship with every native species to be found in our shire.

In short, he is not only a force of nature, he is a force for nature.

You could write a book about this man’s accomplishments in protecting native species and wildlife, not to mention his skills as a musician and luthier (maker of stringed instruments), but let’s start with a two-part series.

In today’s instalment we’ll look at the history of how we’ve treated our land since settlement, as well as a little of Dave’s history, and next week we’ll take a close look at how the programs he manages have helped make Noosa Queensland’s best nature-protected shire, at 42 per cent and rising.

Dave started his nature journey studying horticulture at Gatton Agricultural College and later moved into a decade with what was then the Department of Primary Industry. Later he taught at a TAFE before joining Phil Moran at Noosa Landcare, where his passion for the biodiversity of the shire really took root.

In 2000 he was offered a job with Noosa Council, first working in compliance but soon looking into ways and means of protecting the shire’s wildlife on private property, in the wake of the 1998 establishment of Land For Wildlife in South East Queensland.

But just as the wheels started moving in that direction, Noosa Council was amalgamated into a Sunshine Coast super-council, and Dave found himself co-opted into a much bigger operation, which was good for the region but minimised his focus on his beloved Noosa.

As he says today: “There are a lot of similarities in wildlife across SEQ but Noosa does have quite a few species that you just don’t find elsewhere. It’s a bit of a biodiversity hotspot.”

Soon after de-amalgamation in 2014, Dave was back in Pelican Street, where he has now carried on the work of enlisting landowner support in wildlife protection for almost a decade.

Showing me a PowerPoint presentation he uses for interested landowners at the council chambers last week, Dave pointed to a multi-coloured shire map and said: “This is the latest snapshot of our protected areas and it’s pretty damned impressive, I think. And it didn’t just happen, it’s the culmination of 60 years of community pressure from people like the Noosa Parks Association, with Bill Huxley and Arthur Harrold the driving forces in the ‘60s and ‘70s.

“In terms of native vegetation coverage, the shire has 54.4 per cent which is again well beyond the rest of the state. Within that percentage, 33 per cent is in protected areas and 21.4 per cent is not. The whole notion of my work now is to work on the private properties within that percentage. Creating corridors of connectivity between these areas is important for native animals and for the genetic diversity of plants.”

He pauses for a moment, then flips onto a slide that shows aerial photos of Kin Kin in 1958 and 2022.

“It’s interesting to look at it historically, and the thing to realise is that in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the shire was pretty much completely cleared for agriculture.

“The parallels between 1958 and recently give you some idea but if you went back even further to 1910 it would be completely clear, even the creek lines, with only some forestry retained. The change has come about over the last 60 years because properties have gotten smaller and the generation that farmed steep country died out because it’s no longer viable to farm.

“In the early days the Queensland government would give you a ballot for land on condition that you cleared the land for farming. That’s pretty much the story of Kin Kin.”

Dave flips again, to a photo of a huge old growth tree.

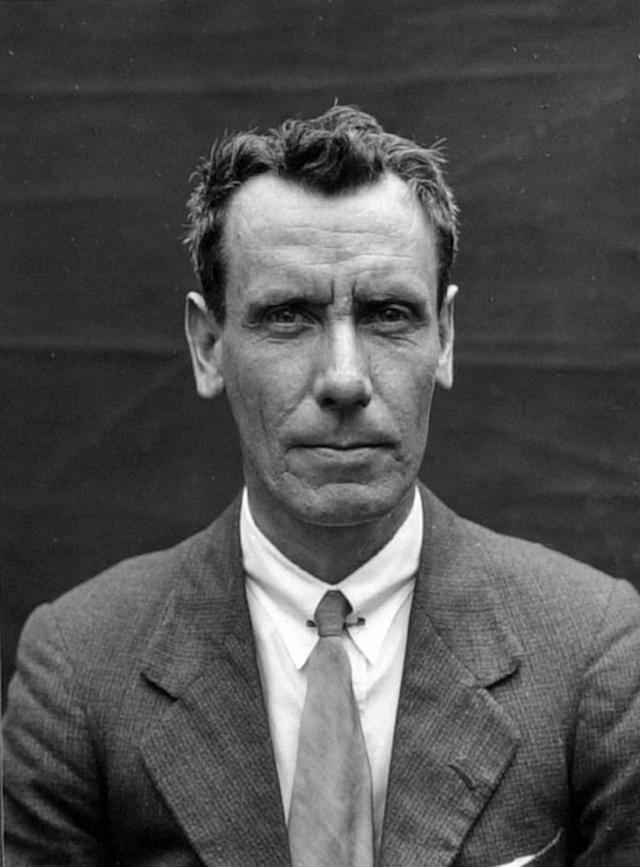

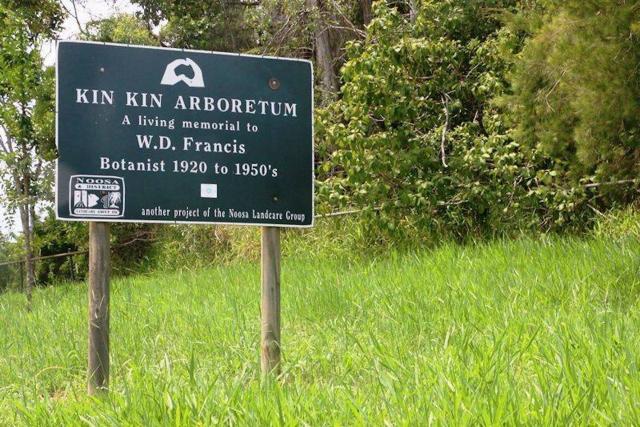

“If you look closely at this picture of the Kin Kin rainforest you’ll see people on horses. That tree, the Syzygium francisii, was named after William Douglas Francis who lived in Kin Kin. He was quite a guy.”

Indeed he was. Francis was born and raised on the south coast of NSW and moved to Queensland in 1906 as a teenager with his father and brother to take up land at Kin Kin.

The surrounding rainforests stimulated an interest in natural history and especially botany, and he soon became proficient in plant identification, learning to recognise rainforest trees by their stems and bark. His collections and observations soon brought him to the attention of the Queensland Herbarium, where he was appointed assistant botanist in 1919, and decades later government botanist.

In 1929 he published the landmark book, Australian Rainforest Trees.

A couple of years ago, Dave Burrows and botanist Bill McDonald led a walk through the property that the Francis family had owned, and later wrote in the Land For Wildlife newsletter: “During the time that Francis was living at Kin Kin, the district was being cleared of its remnant rainforest… using a clearing technique called driving. This is where all the trees on a hillside were partially cut, then a large tree at the top of the slope was felled, causing a domino effect where the entire forest collapsed… Very little remnant rainforest was left from this initial clearing. I have come across occasional large trees retained along the creek or for shade but generally even the creeks were cleared.

“The impact on faunal populations and water quality must have been catastrophic… Apart from some large Moreton Bay figs standing today, most of [the] Francis’ property was also cleared.

“One hundred years later community attitudes and land use patterns have changed in the area. Many of the steep slopes and waterways have regenerated or been replanted with a range of native species. There are now many landowners who see themselves as forest custodians and are nurturing the patches of regenerating rainforest on their properties.”

Switching off the slideshow, Dave says: “I think having a historical context is really important. The value of regrowth is that it’s the land trying to heal itself through natural processes. The wattles and legumes come up first and they enrich the soil and certain species pop up.

“Some people don’t place much value on this kind of vegetation if you want to run cattle or run a farm, but if you just want to bring the bush back this will do it, and if you give it time you’ll have remnant forest again.

“There are some areas of old growth left but not that much, and by that I mean areas that have never been cleared. The white settlers came in and took out all the big kauris, beech and cedar.

“In the presentation there’s a photo of Ringtail Creek where the forestry cleared in the 1970s but they left this little gully, including a 300-year-old tree, because it was a stony gully and too hard to clear. Before the ‘70s that was all remnant forest.

“I guess the story is that while it’s been cleared in the past there are little pockets of jewels across the landscape, many of them on private property.”

And bringing those gems into Noosa’s network of protected land, through various voluntary conservation agreements or council purchases through the Environment Levy, is Dave’s passion for the remainder of his career.

How he goes about it, and what’s in it for the landowner, and everyone who loves nature, will be revealed in our conclusion next week.

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win tickets to see Sharon and Slava Grigoryan present ‘OUR PLACE’](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/sharon-and-slavav-324x235.png)