Retired town planner and academic Mark Baker often reflects on the past, present and future of how we plan where we live, so coming into a relaxed time of year, last week we sat down over coffee in the Bakers’ airy cottage in Boreen Point and tried to put the planning legacy of Noosa’s epoch-making Noosa Beach Estate into some sort of context.

Noosa Today: Mark, where do we start?

Mark Baker: There were two drivers of the modern town planning movement. One was the Beaux Arts Movement that came out of the Chicago Exhibition of 1893, grand boulevards and that sort of thing, and the other was the Garden City Movement of 1898 that came out of England. It was the Garden City disciples who came to Australia [in 1913] where they were sometimes called “missionaries of sunlight”. Amongst the old city slums that we still had at the turn of the century, they promoted the idea of garden suburbs, which they said would get rid of plague and pestilence and allow children to play on grass. What I found remarkable is that when they came back and toured Queensland in 1915 they filled town halls everywhere they went – not with town planners because there weren’t any yet, but people were very enthusiastic about the idea of having clean suburbs and cities. This was happening while there was a world war going on and yet people in the backblocks of Queensland were interested in town planning, an interest which had been kindled years before when, in 1910, the Brisbane Courier had exhorted its readers to be world leaders in town planning.

The second Australian Town Planning conference was held in Brisbane in 1918. How could that come about when you have so many famous names and picturesque towns in European countries? But when you think about it, Queensland was different in that many people owned their own blocks of land, 400 square metres or 16 perches. They weren’t sewered of course, they had a dunny up the back, but they were much better off than the working classes of Liverpool or Manchester, so in some ways we were in front of the game. There were no extensive slums in Queensland like they had in Glebe, Redfern and Woolloomooloo in Sydney, or in Carlton and Fitzroy in Melbourne. The only places we had that even approached them were Woolloongabba and to an extent Spring Hill.

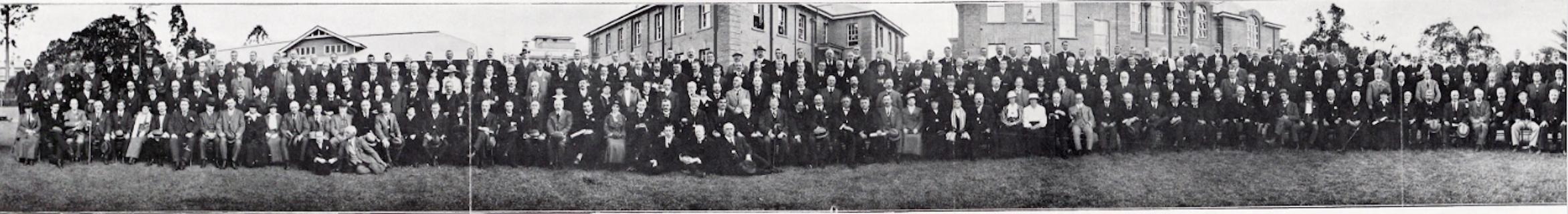

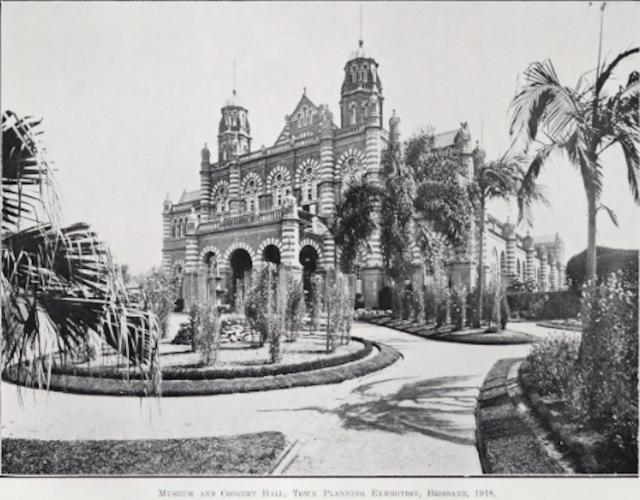

The 1918 town planning conference was held at the building we now call QUT in Brisbane with more almost 600 delegates attending. There was also an exhibition in the old Exhibition Building on Gregory Terrace, of features from modern homes, like electricity and stoves. It was a big deal with the governor opening it, but there were no town planners there because there weren’t any yet.

Within the papers that were delivered a split of ideas emerged. One focussed on the question of who should undertake town planning? Was it the role of government – a political activity – and if so what level of government – state or local? Or should it be undertaken by an independent authority of apolitical experts? That was the conundrum debated at the same time we were going through the early stages of the Greater City movement, which ended up with Greater Brisbane being created, just like Greater Birmingham and Greater Manchester. There was a lot of discussion about infrastructure delivery and planning for the long term, so who does planning was a big important question. Most people thought it should be a statutory authority or the state government, unless you were dealing with a big council, and that drove the idea of Greater Brisbane’s amalgamations. Melbourne and Sydney contemplated the Greater City concept, but in the end adopted the solution of statutory authorities in the form of a Board of Water Supply and Sewerage.

The next split was over the question, what does planning look like? The Ebenezer Howard Garden City model was based on his diagrams of wonderful garden cities which radiated out from the centre with canals and rail lines and parklands, and ideally had a population of about 30,000, created on a greenfield site. These became the models for the satellite towns of Welwyn and Letchworth. Then there were the “incrementalists” who wanted to work with what was already there and improve its liveability. Planners of this ilk included Patrick Geddes. As a result there were varying and competing concepts to emerge from the Brisbane conference.

How did Burley Griffin, who by this time had won the contract to design Canberra, figure in all of this?

Well, he was very influential in terms of greenfield estates, that clean slate approach to design.

Was Canberra our first “garden city”?

No. I’m not an authority but I’m going to say it was Colonel Light Gardens in Mitcham, South Australia, designed in 1917 by Charles Reade and named in 1921 for the man who surveyed Adelaide.

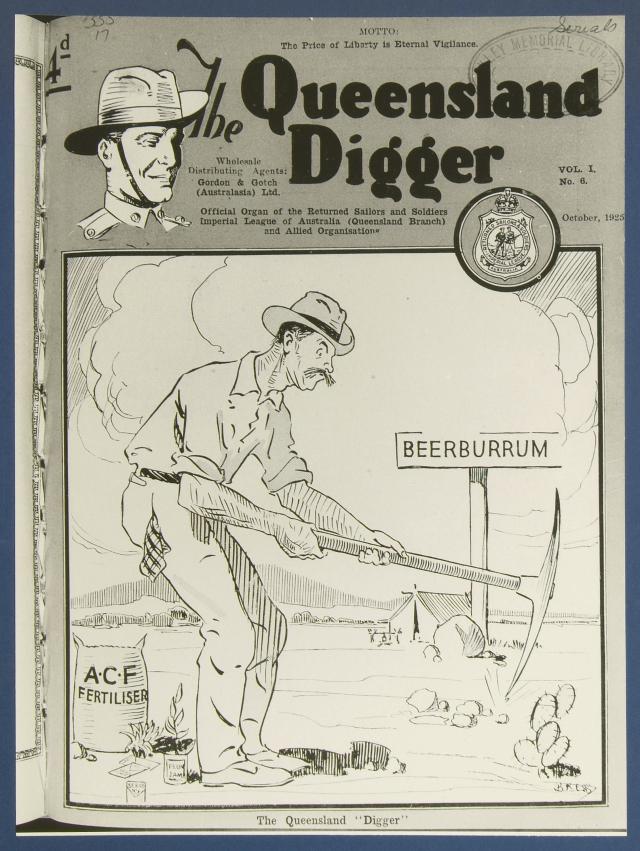

As the soldiers came back from World War I there was a lot of emphasis on creating new suburbs for them, just as there was in America after World War II where there was massive suburbanisation. In Sydney several new suburbs were built, including Dacyfield (1918). In Brisbane in the 1920s we saw the garden suburb of Coorparoo created (1923) and the garden estate of Glenlyon at Ashgrove (1924). On the Sunshine Coast, Beerburrum was created around pineapple growing, primarily for returned soldiers.

Let’s localise the conversation by going back to the epoch-making creation of Noosa Beach Estate in 1929. What happened next?

Well, I have to go back to the division between people at that time who wanted to build grand boulevards and people who just wanted to manage growth and wanted a statutory power that would do that, rather than relying on the government. The first form of control was called “districting” and later became known as “zoning”. Zones were first created for fire protection under the Local Authorities Act, requiring the use of bricks in certain areas rather than wood, and so on. That was the power used in Noosa Beach Estate to create zones. The approach taken by McInnIs at Noosa was to provide a flexibility of use within the zones. This was a significant departure from the more rigid frameworks used in Britain and America.

At the time of the Noosa Beach Estate the impetus for planning legislation had waned. The recently created City of Brisbane had a town planner, the first such appointment in Australia, but he was overwhelmed with traffic issues including the siting of the William Jolly Bridge and creating a traffic circus in Fortitude Valley. These were significant distractions from the task of preparing a statutory town plan. The town planner was confronted with the legacy common to most 19th century cities, that of industries that had been established along the creeks in the middle of residential areas, and other “non-conforming uses”. The outcome was that every time a plan was prepared it was rejected because it ran counter to the economic interests of the city.

So while all this is happening, RA McInnis surveys and plans Noosa Beach Estate and TM Burke used it as a selling point to Noosa Council and prospective buyers. Why he thought he needed to do that is something we don’t know. It wasn’t as if Glenlyon Gardens and his other estates weren’t selling. Possibly it was because he knew Noosa would be a harder sell, having created a greenfield estate in the middle of nowhere with no jobs and no amenities. Why would people live there?

And they didn’t! The Great Depression didn’t help, but it took another generation to pick up the pieces.

That’s true, and another question is, why would the Council take it on without a statutory framework? But they did, and RA McInnis went on to do a town plan for the established city of Mackay, which was a good plan.

Didn’t he do plans for Monto and Theodore before that?

Yes, but Monto and Theodore differed in that they were designed developed by the State in the 1920s and land use controls could be affected through alternative measures.

Let’s look at post-WWII Noosa, where the Noosa Beach Estate is more or less moribund, motorised tourism is still in its infancy and all our councillors are farmers from the hinterland, which is where the council chambers are. How do we move forward?

It’s interesting to note that during those years of a virtual planning vacuum, from the 1930s to the 1960s, the main proponents of planning were rural councils, with Councils such as Inglewood, Texas and Dalby among the first to adopt statutory planning schemes. There were several factors responsible for the dearth of planning undertaken in the period. One was the uncertainty in the planning legislation. The United Kingdom had overhauled its planning legislation in 1944 in a way that provide planners with greater opportunities to rectifier earlier “mistakes”. There was considerable anticipation that Queensland laws would be altered in a similar fashion and planning activities were placed in abeyance. No such amendments were forthcoming. A second factor curtailing the wider adoption of planning schemes was the lack of trained professionals. Many had travelled to Britain to assist in post-way reconstruction and the considerable program of new town development. On their return to Australia they were attracted to the big project of Sydney’s Cumberland County Plan. Only after these, and the establishment of planning courses in Brisbane, was there a supply of planners to undertake the work for the more than 150 local councils.

Coming back to the local picture, why do you think the Gold Coast moved ahead so quickly while Noosa remained a country town?

Before it was known as the Gold Coast, the South Coast had been a popular tourist destination for years because of the railway line to Southport initially, and later to Coolangatta, which meant it was accessible to mass tourism. Getting to Noosa was always difficult, particularly when we didn’t have convenient trains and we didn’t have a coastal road.

And for a long time we didn’t have a town plan either.

Correct. While Noosa Shire Council led the way in 1929 by having a statutory planning scheme over part of its area, what is now Sunshine Beach, the expansion of controls over the remainder of the Shire was slow. In March 1973 a planning scheme over Division 4 of the Shire was gazetted, but it was not until 1978 that the Council passed a resolution to prepare a planning scheme for the entire Shire and interim planning controls were adopted. These afforded some degree of protection in the absence of a plan until a statutory scheme came into effect in May 1985. This was superseded by the 1990 planning scheme and most recently the 2020 Noosa Plan.

Can you give Noosa a report card for town planning in recent years?

I think it’s fantastic, as a refugee from West End in Brisbane which has become just too busy. My mentor in architecture would not build anything over six storeys because he said he liked to be able to look at a person at ground level and see their facial expression. It’s about our relationships with other humans. So I’m all for population caps and building height limits, but I do appreciate that they have their drawbacks, and I’ve long grappled with the question of how we provide affordable housing within that context. I also applaud the other unorthodox strategies the Council has adopted, particularly those of traffic management and commercial centres.

Mark Baker is the author of many papers on town planning, and the book Visions, Dreams and Plans.