After three years of looking at it from the window of my home office, and exploring it on my stand-up paddle board or drifting along it in my rubber duckie inflatable trying to jag a flathead for breakfast, I reckon I know the lower estuary of the Noosa River better than many residents.

Its hidden mangrove passages, tiny islands, sandbars and ever-changing colours are truly a wonder to behold, something that never gets old. But who knew what lived there above the waterline? I love to paddle over the rays sunning themselves in the shallows, and I love even more to haul in a flattie or a couple of decent bream and pull into the Frying Pan island to clean my catch and jump in the water before heading home to cook them. But rarely have I paused to watch the waders feeding on the sandspit, or the harder-to-see birds in the tundra behind. While keen to one element of life on the sandbars, I was more or less oblivious to the other.

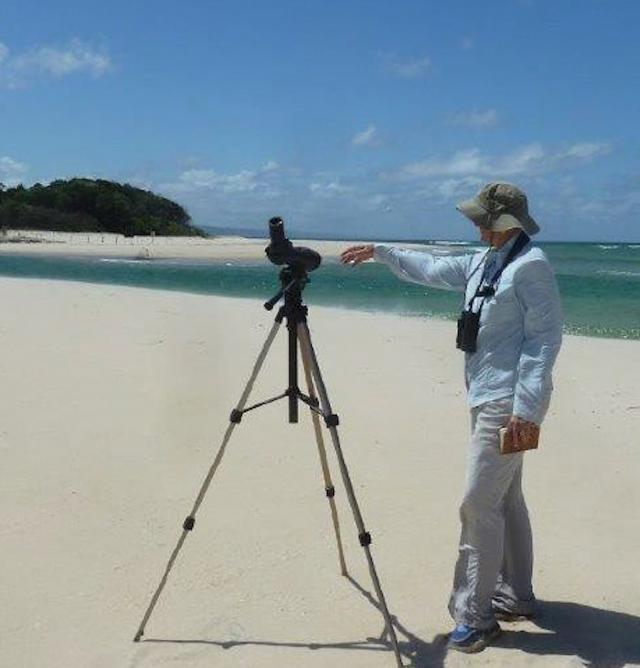

And then the other day I had my eyes opened to a whole new world that I find almost beyond comprehension and yet endlessly fascinating. Guided by the estimable Richard Howard and John Bloomfield, both volunteers with the Noosa Integrated Catchment Association (NICA) which does so much unheralded river research, I found myself standing on the shore of the unnamed (as far as I can tell) and very familiar Frying Pan island and silently following our guides across the sand to a point where he had an unhindered view into the grassy plain behind. Panning binoculars across the plain, I met my new hero, the Bar-tailed Godwit. Let’s call him Bart.

Bart is a handsome fellow with a distinguished slightly upturned bill and a distinctive squeaky voice. He flies a long way to get to Noosa each year and, like many tourists, he then has a big rest and starts eating day and night. But he is not alone. In fact he is one of around eight million shorebirds, some as young as two months old, who migrate to Australia each summer from their breeding grounds in the arctic circle of Siberia and Alaska.

The Noosa River estuary sits directly along the East Asian Australasian Flyway, halfway between the more significant hosting sites of Moreton Bay and the Great Sandy Strait, and hosts numerous threatened or vulnerable migratory shorebirds each year, usually between October and March. As NICA’s Richard Howard explains: “The Great Sandy Strait and Moreton Bay are the two largest Ramsar sites on the east coast. [Ramsar being the city in Iran where the first international wetlands protection convention was signed in 1971.] The birds will fly between these two protected sites and stay for varying periods in Noosa. But our estuary is very small. There are 66 Ramsar sites of international significance in Australia and we’re not one of them. You need to prove that you hold at least 1 per cent of the global population of shorebirds. Sandy Strait can prove that multiple times, Moreton Bay a few times over, but Noosa cannot, although we got very close in 2005. However, we are a habitat of national significance.”

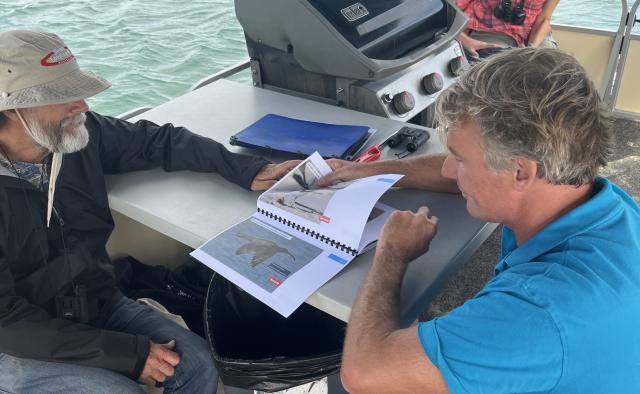

Which is why NICA is partnering with Tourism Noosa in the creation and presentation of Enter The Flyosphere, one of six brilliant new tourism experiences introduced this month under the Tread Lightly banner. Enter the Flyosphere will offer a guided tour of the biodiverse Noosa River estuary and islands to understand more about migratory and native shorebirds “as they rest and forage on our doorstep before commencing their long return migration”, to quote the Tread Lightly website. I was one of a boatload of lucky folk who got to trial the Flyosphere experience and, even though I thought I was well-informed about life on the sandbars, it turned out I knew very little, particularly about the likes of Bart. We’ll get back to Bart in a minute, but first a few reasons why Noosa is such a special shorebird habitat.

NICA has been surveying, studying and observing our shorebirds on a monthly basis since 2005, submitting its data to the National Shorebird Monitoring Program and although both Richard, also a member of the Noosa River Stakeholders Advisory Committee, and John, a former research skipper at the Australian Institute of Marine Science, admit there are still gaps in the accumulated knowledge of the behavior of these remarkable birds, they know a hell of a lot, starting with the fact that almost half of all migratory shorebird species known to visit Australia can be seen in Noosa. However, habitat loss along the flyways and increased disturbance locally is putting this hotspot of shorebird biodiversity at risk.

As Richard noted while we quietly observed Bart: “The Godwit is a unique specimen. We see about 10 to 20 groups of them on any given survey. You can imagine how they feel when a jet ski comes whizzing down the river and disturbs their environment, particularly after it’s taken so long to get here.”

Which brings us neatly back to my new hero, Bart, and his mates. Says Richard: “They fly over 12,000 km without stopping and they tend to go off course, which when you’re coming from Alaska is a bit of a problem. But they use weather systems to help them keep flying, and we’re still learning how they do that. Incredibly they have a 90 per cent survival rate. They take off on one side of the world and fly to the other but they have no idea of where they’re going and yet they get here. And when they get to where they’re going, they flop down for a while and then they start eating.” Who wouldn’t?

In 2007, not long after NICA began its monitoring, a Bar-tailed Godwit hit the headlines, after a bird, known as E7, was recorded flying non-stop from Alaska to New Zealand — a journey of more than 11,500 km, in 11 days. It was a world record, with the information made available via a tiny satellite transmitter attached to the bird’s back. Although E7’s record has been broken incrementally a number of times since, this year Birdlife Australia reported that it had now been smashed by another Godwit, a five-month old juvenile which flew an even more astonishing distance of 13,560 kilometres from Alaska to Ansons Bay, on the north-eastern coast of Tasmania, more than 2000 km longer than E7’s epic flight.

As Birdlike Australia reported: “And this non-stop flight was completed in just 11 days. Indeed, this bird had ample opportunities to stop over for a feed and a rest on a number of tropical islands as it winged its way across the Pacific Ocean, but chose to keep on flapping instead.”

Again mimicking the behavior of human tourists, migratory shorebirds sometimes forget to go home, making the return journey after the next summer. But don’t get the idea that it’s all beer and skittles out there on the sandbars for Bart and his mates. Says Richard: “What most people don’t realise is that shorebirds don’t prefer cover. They like a bare sandbank where they rely on their wits to survive, and their primary threat is the eagle. But a grassy landscape allows them to see any threats better than a mangrove environment. And tall trees provide cover for eagles.”

Eagle predators, speeding jet skiers, declining habitat, endless flapping over lonely oceans, a shorebird’s life is not for the faint-hearted. When I finally put down the binoculars as Bart moved behind a tussock, I offered a silent salute to an amazing creature.

The next Enter The Flyosphere shorebird experience will be on 2 February, for more information visit treadlightlynoosa.au