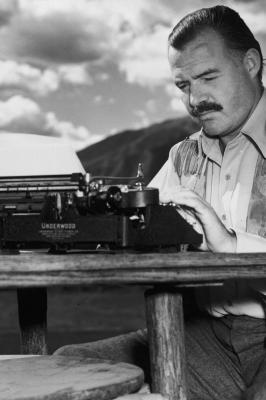

The old man always thought of her [the sea] as feminine and as something that gave or withheld great favours, and if she did wild or wicked things it was because she could not help them. The moon affects her as it does a woman, he thought.

– Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man And The Sea

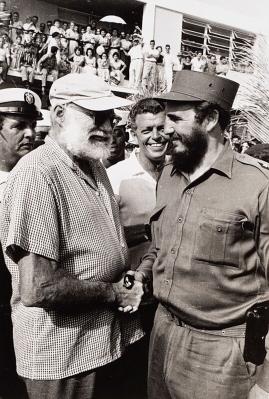

In my home office, just over my left shoulder, hangs a big black and white print of Alberto Korda’s 1960 photograph of Ernest Hemingway shaking hands with Fidel Castro, the new dictator of Cuba.

I glance over at it often while writing, because it reminds me that despite his celebrity lifestyle, mixing with the great and the good, not to mention the dangerous and dodgy, when it came to his writing, “Papa” always kept it simple.

I’ve read Hemingway since I was a teenager, but I was only recently reminded of the beautiful simplicity of his words while watching Ken Burns’ excellent Hemingway documentary series on SBS. Burns, the acknowledged master of the documentary, and Hemingway, whose 10-word sentences conveyed so much more meaning than they should, was always going to be a formidable duo, but the masterstroke was to have actor Jeff Daniels read Papa’s words.

At one point, Daniels reads from a letter Hemingway wrote to his father: “You see I’m trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across—not just to depict life—or criticise it—but to actually make it alive. So that when you have read something by me you actually experience the thing.”

It seemed to me that in reading that dumbed-down explanation of Papa’s style, the penny dropped for Daniels, and in listening to him read Hemingway over the six hours of the series, the penny dropped for me too. It’s the rhythms, the cadence of the words that count. To really appreciate Hemingway, you have to read him aloud.

I once wrote a narration script for a documentary that was to be narrated by the Hollywood actor Ed Norton. Norton returned my script with just a few minor changes, which made me happy, but when I heard his read on a rough cut of the film, I was ecstatic. He gave my words meaning they didn’t deserve, and he lifted the film many notches by doing so.

Daniels’ read of Hemingway is quite different, because the power of the sentence construction is already there, but only with the right delivery can it be shared.

Hemingway wrote convincingly about the ocean and its moods, although he gets a bit hairy-chested when it comes to rationalising his passion for game fishing. As far as we know, he never surfed nor tried to write about it, which is probably just as well when we look at the great writers who did.

In the second half of the 19th century, Mark Twain (aka Sam Clemens) was the most popular writer in North America, both for his travel journalism and his novels. In 1866, at the height of the missionary purge of the Hawaiian islands of ungodly traditions such as nudity, surfing and sex on the beach, Twain fetched up in Honolulu and later wrote in his book, Roughing It: “In one place we came upon a large company of naked natives, of both sexes and all ages, amusing themselves with the national pastime of surf- bathing. Each heathen would paddle three or four hundred yards out to sea (taking a short board with him), then face the shore and wait for a particularly prodigious billow to come along; at the right moment he would fling his board upon its foamy crest and himself upon the board, and here he would come whizzing by like a bombshell! It did not seem that a lightning express-train could shoot along at a more hair-lifting speed. I tried surf-bathing once, subsequently, but made a failure of it. I got the board placed right, and at the right moment, too; but missed the connection myself. The board struck the shore in three-quarters of a second, without any cargo, and I struck the bottom about the same time, with a couple of barrels of water in me. None but natives ever master the art of surf-bathing thoroughly.”

Nearly half a century later, the adventure writer Jack London sailed into Honolulu and also had a dig, as recounted in A Royal Sport: Surfing at Waikiki: “I shall never forget the first big wave I caught out there in the deep water. I saw it coming, turned my back on it and paddled for dear life … I heard the crest of the wave hissing and churning, and then my board was lifted and flung forward. I scarcely knew what happened the first half-minute. Though I kept my eyes open, I could not see anything, for I was buried in the rushing white of the crest. But I did not mind. I was chiefly conscious of ecstatic bliss at having caught the wave.”

Better, but no cigar.

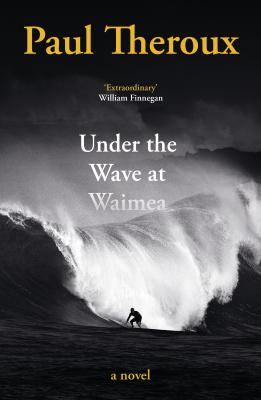

A century or so on, the esteemed travel writer and novelist Paul Theroux, who has lived on the North Shore of Oahu for more than 20 years and ought to know better, has tried to invent his own world of surfing in which real-life surfers and countercultural figures, like Hunter S. Thompson, cohabit, in a strange novel called Under The Wave At Waimea, which I’ve just finished. I don’t want to pick nits in the work of an 80-year-old who has written some absolute gems, but Theroux just doesn’t get it. He thinks when we surf, we “swim” out to the break!

As surf historian Matt Warshaw wrote: “The fault here is not that Theroux is an outsider. That’s fine. Some of the best takes on the sport have been made by outsiders. But the writer has to care enough, be interested enough, to make something previously unknown to him or her come to life.”

Hear, hear.