Having spent most of my life looking at photos of people riding surfboards, it’s not something I tend to seek out as a leisure pursuit in my golden years.

True, my bookshelves are cluttered with hundreds of extravagant coffee table trophy books, some of which I’ve had a hand in creating. And let’s not even consider the cupboards and storage shed full of archive boxes of old magazines featuring more of the same. To be honest, I’ve rarely looked at these vast collections in decades.

But then a couple of things will happen to remind you of the incredible journey on which the best surf photographers have taken us, and you look with fresh eyes.

The first of these was old mate John Ogden’s recent launch of his opus, Waterproof: Australian Surf Photography Since 1858, a magnificent collection of historic photographs and explanatory text that has rightly been attracting attention from a variety of media sources, ranging from Tracks to The Scotsman. I’ve known Oggy for something approaching 50 years, we’ve helped each other out on various projects and I’m a big fan of his photographic compilations, particular the brilliant Saltwater People series, and decades before that, his stunning black and white Australienation, so I’m not surprised the long-awaited new book is getting some traction.

In Waterproof, Oggy writes: “With more players entering the field, we are seeing many sensational images, but also a vast mass of dross as cameras blaze away in machine-gun bursts to be edited later. We are now bombarded with so many images that it is becoming increasingly difficult to stand out from the crowd.”

This book reminds us that there was a time before dross, and that even when surf photography was in its technical infancy, brave men (yes, almost exclusively men back then, although I dips me lid to the brave and beautiful Shirley Rogers) would swim out into a raging sea with a plastic bag over a Box Brownie to get the shot. Not quite “waterproof” but unforgettable.

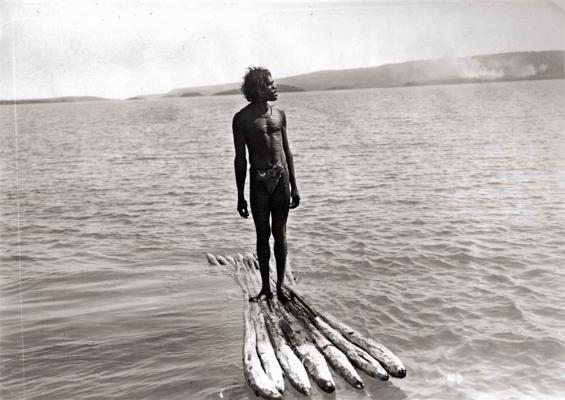

Of course, there was no such thing as surf photography in 1858, but Oggy cleverly justifies his startling subtitle by referencing photographers of the “surf zone”, who shot seascapes of places such as Bells Beach without the slightest idea of what craziness would occur just off those rugged cliffs in the century to come. Further excavation of surfing photography’s pre-history reveals many shots this surf historian has never seen before, including the 1917 gem of Sampson, a Worora “tide rider” from north-west WA, which captured Tracks editor Luke Kennedy’s attention.

Luke wrote in his review: “Amongst the book’s various images of early Australian beach culture, there is one in particular that stands out… A tall, athletically built Indigenous man whose chest and abdomen are striated with the scars of initiation, Sampson is pictured standing proudly aloft a raft of seven mangrove logs. His stance upon the floating craft belongs every bit to the nonchalant longboarder who rides a wave with confidence and skill.”

Yep, he’s got the look. With just the puff of a wave beneath him, Sam would fit right into an average longboard sliding day on Noosa’s points.

Waterproof: Australian Surf Photography Since 1858, by John Ogden, Cyclops Productions, is available at cyclopsproductions.com.au

The second thing that made me look again at surf photography was that a dear friend turned up at my place unexpectedly with an unexpected gift of WA photographer Russell Ord’s Surfing: Water Is Freedom. No explanation, he just saw the book in a shop and thought of me.

The book, published in 2018, is as splendid as the gesture. Like most surfers, I’ve been aware of Ord’s textural masterpieces for quite a few years – and his work also features in Waterproof – but Water Is Freedom had slipped under the radar. While focusing on the texture of waves is not new – Art Brewer was a pioneer 50 years ago and Clark Little and Jon Frank are modern masters – Ord has made the form his own.

Yes, there are plenty of shots of people riding waves in this book, but even then, Ord tends to focus on the majestic power of the ocean as much as the rider, particularly at so-called “waves of consequence”, such as Shipstern’s or Pipeline. But give me the textural abstracts that make up the first 20 pages of this book any day.

I have been a judge of the Surfing Australia/Nikon Surf Photography awards for several years now, and I can tell you that Ord, Frank and company are by no means alone in this pursuit. But I know a true master when I see one, and you are that, Russell.

Time for a change

Almost eight years have passed since a small group of Noosa surfers and stakeholders met with National Surfing Reserves founder Brad Farmer to discuss the creation of a Noosa National Surfing Reserve.

I led the steering committee that was formed to make this happen in 2015, and the subsequent stewardship council that succeeded in having Noosa approved as the 10th World Surfing Reserve in 2017 and dedicated in 2020. Since dedication, the stewardship council has been even busier, creating a surf code to address safety and behavioural issues, securing funding for the installation of defibrillator units from one end of the NWSR to the other, and working with local and state government to ensure maintenance and protection of our surfing assets.

The work goes on, but it’s time for a change, so last week I stepped down as president of the Noosa World Surfing Reserve. I’ve loved every minute of working with a talented, energetic and dedicated team, that still includes foundation members Di Cuddihy, Libby Winter and Chris Doney, and look forward to continuing to help from the back bench.

Next week in Noosa Today, you’ll meet the new president.