I thought I knew the story of Maya Gabeira’s courageous but perhaps misguided quest to ride the biggest waves in the world: turns out I didn’t know the half of it.

The Brazilian surfer, model and crusader for recognition of women who dare to venture into the boys club that is big wave riding, turned 38 last month, marking 21 years since she left Australia (where she’d been an exchange student) to test her skills and courage in Hawaii. It’s been a hard road since, being dragged from the turbulent shorebreak at Nazaré, Portugal technically dead, and having had more fusions in her back than most surfers have had memorable wipeouts. She lives daily with pain, but she looks great and the spirit is undiminished.

There’s a lot to like about Maya Gabeira, but I have to confess that ever since I first heard of her giant wave obsession some years ago, I’ve tended to agree with the argument expressed by some of the legends of big wave surfing, Laird Hamilton and Garrett McNamara specifically, that her lack of the necessary skills puts others at risk every time she tows into a 20-metre monster wave. Granted, that argument has waned somewhat as Maya learnt on the job and became expert on the jet ski and technically adequate on the wave – McNamara has now become a supporter instead of a critic – but her list of life-threatening injuries far outweighs those of any of the leading men in the big wave sector.

That said, Maya has succeeded in riding the biggest waves ever ridden by a woman (she claims by anyone) and has two entries in the Guinness World Records, for riding a 20.8-metre Nazaré monster in 2018, and then breaking her own record there in 2020 with a 22.4m wave. After a long crusade, Maya succeeded in getting the World Surf League to recognise her achievements.

All of these fights, tears, fears, excruciating pain and absolute joy are brilliantly documented in Stephanie Johnes’ Maya and the Wave, a film which has been around for a while now, picking up gongs at several film festivals along the way, and which I was privileged to enjoy at its Noosa screening last week, thanks to a phone call from old mate Tim Bonython when I was halfway home from Agnes Water, telling me he was saving me a seat. I stepped on the gas and into the packed cinema just as the lights went down.

As I sat transfixed, watching the high drama of Tim’s exquisite water footage of Nazaré (and Maya) in full flight, and the behind the scenes story of Maya’s dogged persistence against all odds, all I could think about was what drives her? What keeps her putting her life at such risk when so many of us would say enough, I’ve made my point?

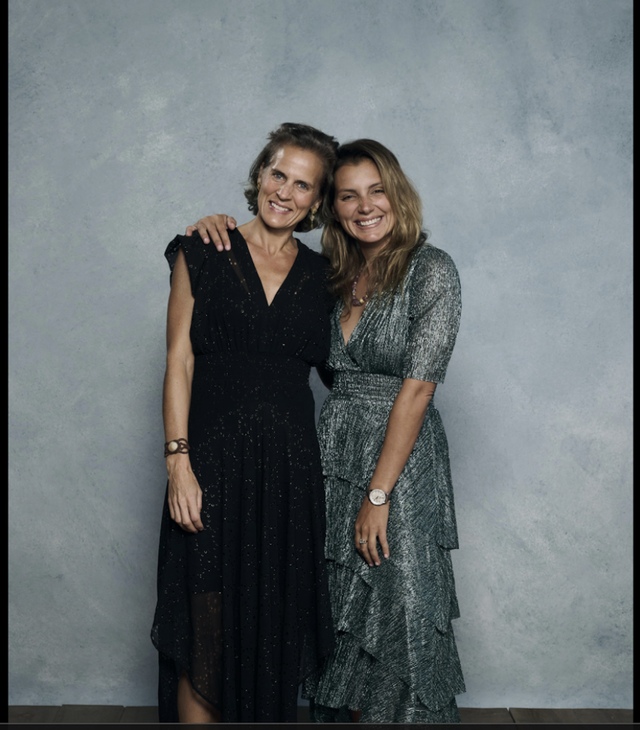

Maya’s parents, former politician and activist father Fernando Gabeira and fashion designer mother Yamê Reis both feature in the film, seen as strong-willed people in clearly supportive roles. But what is not explored is the impact their divorce 25 years earlier had on Maya’s future. Traumatised by the split, Maya fled overseas at just 15 to pursue a career as a pro surfer, a sport she had only started in the previous year. After failing to make inroads on the shortboard world tour, she began to chase glory in huge waves, supported financially by Red Bull, who saw her passion and cover girl looks first, her surfing ability second.

Both Reis and Gabeira have remained supportive of their daughter through her ups and downs, but it is only when you look into Fernando Gabeira’s history that you suddenly see where all of this is coming from. Now 84, Fernando became a distinguished writer and editor in Rio De Janeiro in the 1960s, before joining the armed struggle against the military dictatorship with the 8th October Movement. In 1969 he was part of a group that kidnapped the former American ambassador to force the release of political prisoners, a drama portrayed in the 1996 film Four Days In September. Gabeira was arrested, imprisoned where he was tortured for months, and eventually exiled.

After 10 years in exile, during which he reported from the frontlines on the overthrow of Allende in Chile in 1973, an amnesty allowed him to return to Brazil in 1979. He spent the next decade or so becoming one of Brazil’s leading voices on human rights and environmental protection, eventually entering politics in the 1990s, where he was appointed federal deputy in 1994 and remained one of the highest profile politicians in Brazil until retiring in 2011.

Although the father’s activism is a world away from Maya’s passion for huge waves, you can see that the apple didn’t fall far from the tree. Neither of them know the meaning of surrender.

Unfortunately Maya and the Wave won’t be back in Noosa this tour, but if you’re in NSW over the next few weeks, check these dates: Warrawong, Fri 30 May, 6:45pm, Gala Cinema; Ulladulla, Sat 31 May, 5pm, Arcadia Cinemas; Cremorne (Sydney), Tue 3 June, 6:15pm, The Orpheum; Club Palm Beach, Wed 7 June, 7:45pm.

Jack’s back!

Quick reminder, still some seats left at Nambour Cinema tomorrow night for Jack McCoy’s screening of the 20th anniversary high def version of the classic Blue Horizon. This great surf flick tells the tale of two brilliant but very different surfers, Andy Irons and Dave Rastovich. Derek Hynd, who worked on the production, will join Jack and me for a rousing Q & A. Show starts 7pm, Nambour Cinema, Saturday 24 May. Tickets at jackmccoy.com

FOOTNOTE: The Margaret River Pro got underway last Saturday in pumping conditions at Mainbreak. Coupla pics from Day One here, full report next week.