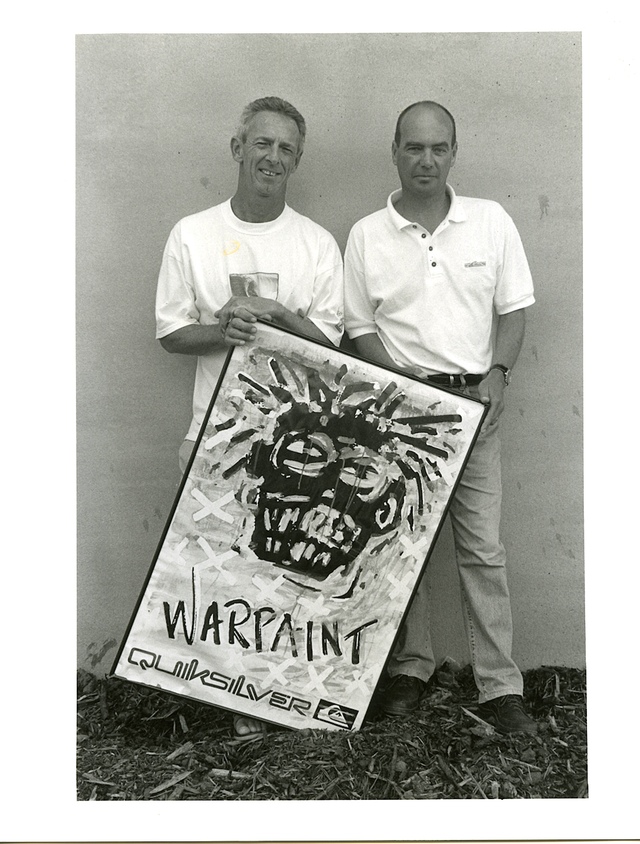

Quiksilver founder Alan Green, who died last week at 77, was a creative genius and branding wizard disguised as an average bloke from Pascoe Vale, and over the 50 years I knew him, through the highs and lows of a business career in which he created greater wealth than he can ever have dreamed of, fundamentally he never changed.

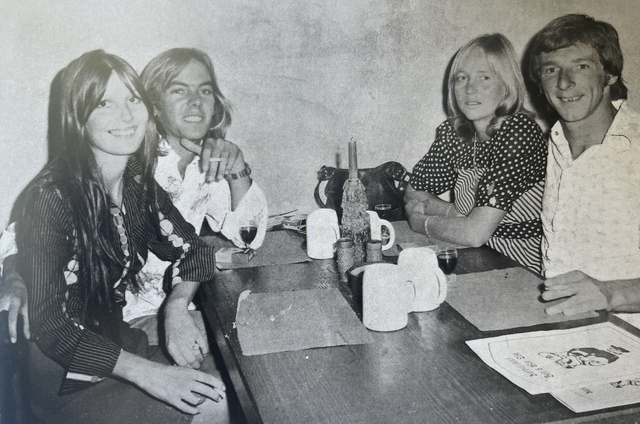

When I first met Greeny in 1975 he claimed he couldn’t afford a couple of hundred bucks to take a half-page ad in Tracks, Australia’s top-selling surf magazine. When I was appointed Quiksilver Entertainment’s special projects manager 30 years later, based out of the Huntington Beach HQ, my first assignment was to write the incredible true story of what was then the world’s largest surf brand, its revenues approaching $3 billion.

The story was so good that I had to write it twice, apparently because the first version painted a larrikin rendition of Quik’s Australian roots that was unpalatable to the then-current management cartel who were far more interested in the stock price than the origins of a legacy surf brand. And you have to understand that by this century, Quiksilver, a public company in the US since 1986, had pretty much written Australia out of the script.

So, told by the suits on the board to start afresh with something akin to an annual report combined with a look book, or else clean out my desk by Monday, I filled V2 with glowing predictions from sales managers and gushing blah blah about Quiksilver Now, which ironically was about to fall off the precipice.

But parts of the first version survived, mainly through the insistence of the true founder of the brand that the story be told. The big problem was that Alan Green, a great pub yarn spinner, was reluctant to claim credit, beyond the blood-spattered boardroom, for his legendary achievements. Having spent plenty of surf time and bar time with Greeny since the very early days of the brand, I knew that I had to open up his saltiest vein to get the story, so I chased him all over and ended up sitting on the terrace of his Mount Buller chalet, drinking a good quaffing red as snow flakes started to fall from a darkening sky, and I said: “Okay Greeny, tell me a surf story.”

All of us who were at the Bells Pro that huge and perfect day in 1981 when Simon Anderson showed us what the three-finned thruster could really do will never forget it, but typically, Greeny had a different take, one from around the corner at Winki Pop. He took a long drag on one of the darts that would eventually take him from us, and he began:

“When Paul Smelly Neilsen [Greeny’s brother from another mother and a sensational surfer] and I went down to Winki Pop around midday it was very big, regular and perfectly offshore. I told Smelly that we needed to make for the ‘button’ area, to get trajectory with the rip, so we rock-hopped along under the cliff at high tide. From out of nowhere, a big set hit the point and sent a five-foot wall of whitewater sideways along the base of the cliff. I dived behind a boulder and braced myself. When the impact had passed, I looked for Smelly, way down the line with three or four waves still to deal with.

“We started to paddle again but huge waves kept breaking in front of us. Then finally a lull, and the surge took us quickly into the lineup. As we stroked to get over another 15-foot set, we saw Nat Young, sitting out in the middle of the bay alone. We paddled out to him and compared notes. Our main concern was getting in at high tide without being crushed against the cliffs, but we put that out of our minds temporarily as we marvelled at the huge corduroy perfection of the sets.

“We caught a couple of waves each and things began to settle down a bit. Then suddenly another huge set loomed outside and we paddled frantically for the horizon. When the set subsided we sat there and took in the markers, trying to establish where we were. It was ridiculous, the swell probably peaking right then. The talk turned again to the problem of getting in. Smelly was terrified of coming ashore at Winki and favoured paddling around and catching one in at Bells, through the middle of the contest. My plan was to pick up a wave way up the point, bail out in front of the target landing zone and get pushed in by the rolling whitewater.

“Jumping off a big wave was tricky for me but when mine came I kept an eye on the cliff-line and as it seemed to be dead ahead, I turned up into the top of the wave, dropped back down and stepped off the back of the board. I got tumbled along, but I was behind the primal action and covering distance. I caught a breath and there I was at the landing, safe and sound.

“As I reached the top of the cliff, I heard a PA announcement and looked out across the bay to see Smelly and Nat paddling way outside of Rincon beyond the heat in the water. A set appeared and Nat took the first huge wave and rode it from Rincon to the sand. Smelly took the next, an even bigger wave. He pulled high into it and drove across the saddle at high speed until the huge face started to barrel in front of him, set his trim and pulled into the barrel, never to emerge! The contestants in the water just watched and wondered.”

That was one of the things I loved about Greeny. He made a motza from the industry but for him it was always about the culture, and he never lost the stoke.

RIP, old mate.