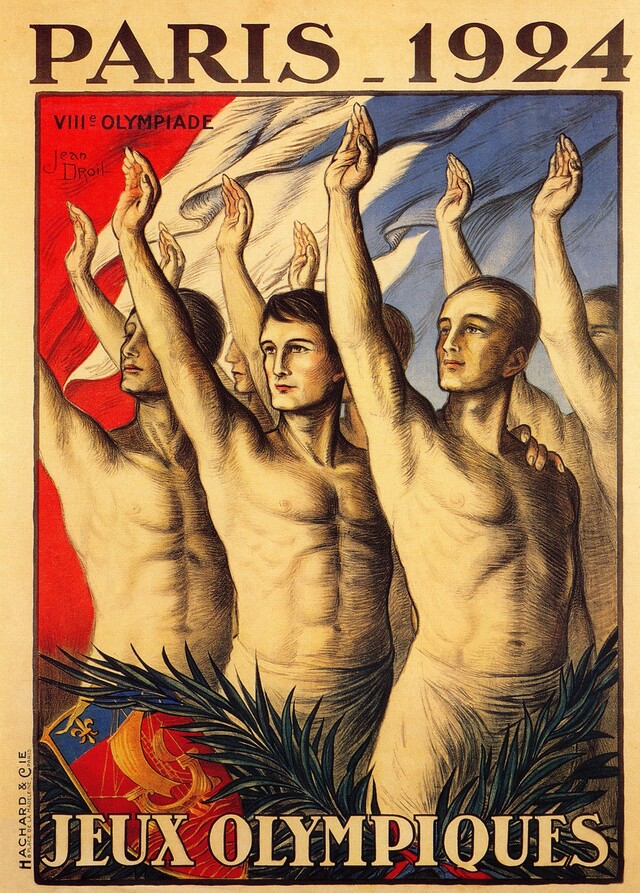

The selection of Paris for the 1924 Olympic Games is of interest for several reasons. It was the first city to host the Games a second time. It was close to Antwerp and Belgium, hosts of the immediate post World War One Olympics. Other cities which bid to hold the 1924 Games were Amsterdam, Barcelona, Prague, and Rome; the only non-European bidder was Los Angeles.

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the acknowledged founder of the Games, assumed the International Olympic Committee (IOC) presidency after the inaugural 1896 Olympics. He had made clear his ‘final Olympics’ would be in 1924. Perhaps it was also an acknowledgement of his longstanding contribution to the Olympic Movement that the Games were again held in Paris.

At Coubertin’s suggestion the Latin expression “citius” “altius” “fortius” meaning in English “faster.” “higher” “stronger” and coined by Father Henri Didion, a French schoolmaster became the Olympic motto of the IOC.

Another first, which showed the IOC was becoming very influential, was its negotiation to obtain exclusive rights to film and photograph the 1924 Paris Olympics. Paris was also the first Games broadcast by live radio.

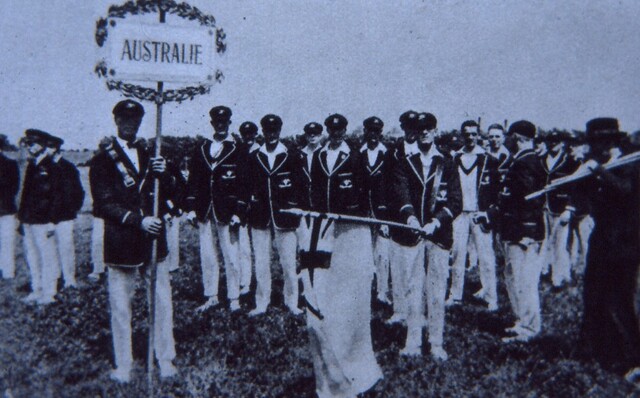

It was also in Paris that all athletes stayed in an Olympic Village for the first time. And there were over 3,000 of them from 44 countries: 2,956 males and 136 females. Athletic rivalry was paramount, especially between the USA and Great Britain; as shown in the multi-award-winning film of 1981, ‘Chariots of Fire.’

Director Hugh Hudson’s based the screenplay on two British champion runners – Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross) and Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson), and two other key persons: Abrahams’ coach Sam Mussabini, and a fictitious 40- metre hurdler, whose name in the film was ‘Lord Lindsay.’ More about ‘him’ later.

The film addressed contemporary issues, including amateurism and professionalism, the role and place of coaches, race and religion, and international rivalry. If you have yet to see the film I won’t spoil it for you in this article but I do urge any lover of the Olympic Games to see it as it is acknowledged as one of the best ‘sports’ films ever.

However, do note that there is considerable ‘cinematic licence.’ Whereas Harold Abrahams, an English Jew, and Eric Liddell, a Scottish minister of religion, are winners of Olympic gold medals at those Paris Games, ‘Lord Lindsay’ is actually Lord David Burghley, the 6th Marquess of Exeter, who won his gold medal in the 400-metre track at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. But it makes a good story, if not accurate history.

The brilliant soundtrack music by Vangelis also won an Academy Award.

Although they don’t feature in the film, what is accurate are the efforts of another ‘threesome’ – all from the Sydney suburb of Manly, They are swimmer Andrew ‘Boy’ Charlton, diver Richmond ‘Dick’ Eve, and triple-jumper Anthony ‘Nick’ Winter.

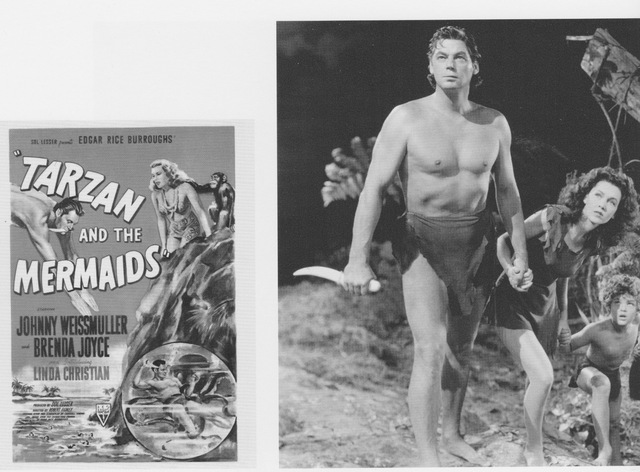

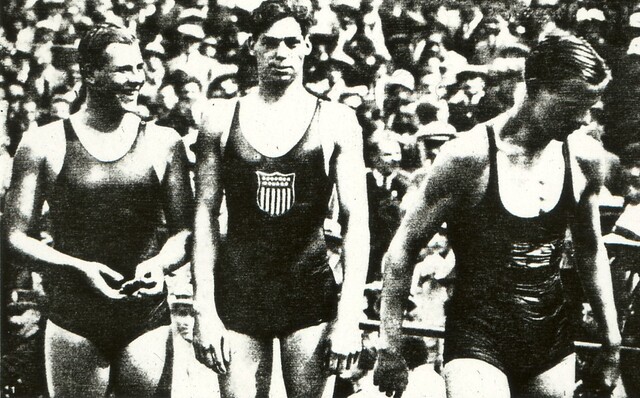

Boy Charlton swam against American Johnny Weissmuller (later to become ‘Tarzan’ and ‘Jungle Jim’ in many Hollywood movies) and the Swede Arn Borg). They had many international tussles but it was the laid-back Charlton who won the 1,500-metre swim in Paris. ‘Boy’ also featured in a song titled ‘The Wonder Boy Charlton’, and in 1968 the new Sydney Domain Baths were named after him.

Dick Eve won the Plain Dive Competition – which meant no somersaults or twists – from the 10metre platform. Eve’s final ‘swallow dive’ was near perfect: it earned him a standing ovation from the predominantly French crowd and the gold medal.

The hop-step and jump, now known as the triple jump, was first included in the Australian Athletic championships in 1930. This was six years after Nick Winter set a world record at the 1924 Paris Olympics with a distance of 15.52 metres.

The 1924 Games were the third and last occasion swimmer Frank Beaurepaire competed. He had medalled at the 1908 London and swam in the 1500 metre event at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics. He won a silver and bronze medal in 1924.

Beaurepaire was unable to compete at the 1912 Stockholm Olympics. He was considered a professional because after his world-record breaking sojourn in the United Kingdom and Europe in 1910, the Victorian Government gave him a house in Middle Park, and made him Director of Swimming in the Department of Education.

It was after the Paris Games that he established his tyre company, first known as ‘Olympic Tyres’ and it is still in business today as “Beaurepaires.”

Thirty-three male athletes competed in Paris in athletics, boxing, tennis, rowing, swimming, diving and wrestling. At the 1912 Stockholm Games, Sydney-siders Sarah ‘Fanny’ Durack and Wilhelmina Wylie came first and second respectively in the 100 metres freestyle. And Lily Beaurepaire, Frank’s sister, competed in swimming and diving at the Antwerp Olympics. But there were Australian female competitors in Paris.

Athletics for women was first introduced at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics only after the IOC finally acquiesced when European women led by Madame Alice Milliat in France organised the Federation Sportive Feminine Internationale (FSFI) to organise competitive sport globally for women. But that’s another story.

[Dr Ian Jobling is Founding Director, UQ Centre of Olympic Studies, now Honorary Patron, Queensland Centre of Olympic and Paralympic Studies, University of Queensland]