By Phil Jarratt

After the frenetic pace of a week or so of surfing, eating and drinking on Bali’s south-western coast, we took a weekend break in sleepy Sanur, to do pretty much nothing, other than laze around, be massaged and catch up with some mates.

So I checked us into the Besakih Beach Hotel, one of those old-school Bali hotels where I love the garden statuary and the overgrown lawns and know I’m going to hate the wi fi connectivity and the water pressure.

But beachfront and right next door to the even older but still fabulous Tandjung Sari (and at a third of the price) who’s complaining?

First on the catch-up list was our old pal Arthur Karvan, the flamboyant, articulate, black-eyed grand wizard master of Sydney’s best nightclub of the ‘70s and ‘80s (the eponymous Arthur’s), these days better known as the dad of a famous daughter, and as Bali’s most argumentative Buddhist. Arthur is always brimming with wonderful stories, and last Friday night at Massimo was no exception.

That very day, he said, on his morning walk along the beach from Batujimbar to Segara, he had confronted a young developer who was overseeing the laying of a concrete construction slab over the sand of a public beach. Only his advanced age and his pious nature had prevented a fist fight ensuing.

Sanur has always had its share of colourful bule (or Westerner) characters, from the fashion photographer Jack Mershon and his dancer wife Katharane in the ‘30s, to the painter Donald Friend and Wija Wawo-Runtu, the Dutch-born creator of the Tandjung Sari, in the 1960s.

Not being very good at doing nothing for long, I decided to spend some of my weekend learning about Adrien-Jean le Mayeur de Merpres, another character from the ‘30s whom I had touched on a few years earlier in my book, Bali Heaven and Hell.

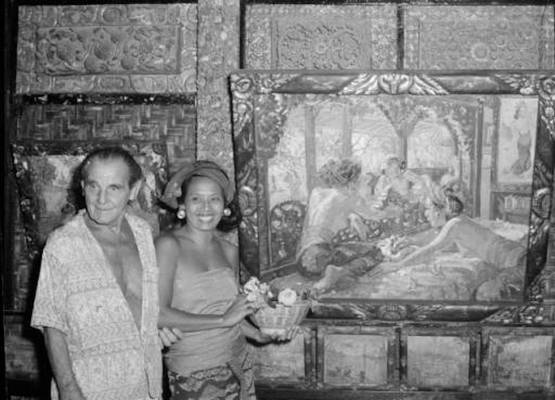

A well-travelled and well-connected Belgian artist, Le Mayeur was already in his fifties when he arrived in Sanur. He was said to be connected to the Belgian royal family, but in Bali he was chiefly famous (and somewhat notorious) for his marriage to the young (15) Balinese dancer who modelled for his paintings, the exquisitely beautiful Ni Nyoman Pollok.

Visitors to the Le Mayeur beachside compound were amused to be greeted by the middle-aged painter, naked except for a sarong knotted under his considerable belly. But they were rendered speechless by the arrival of Ni Pollok, bearing the drinks tray on her head, her stunning breasts and tight brown stomach bare above her sarong.

One 1930s visitor wrote: “A tall young woman came sedately towards us, her smooth, brown body, clothed only in a sarong, was broad-shouldered and narrow-hipped. Her breasts floated in vigorous curves. Her face had the dignity of a Greek marble, with large eyes and sensual but clean-cut lips. Her black hair was brushed back and her pierced earlobes were distended with gold plugs. She would have been a sensation in any drawing room, in any kind of clothes.”

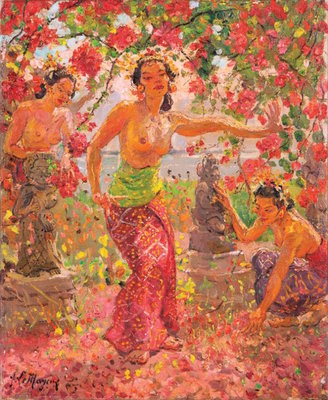

Wanting to visualise this scene with my own goggle-eyes, I set off up the beach for what is now the Museum Le Mayeur, a mostly-overlooked minor jewel in Bali’s cultural crown. The old beach compound, hidden away behind the noisy, crowded, Nusa Lembongan fast boat services, has seen better days. Most of the furniture has been removed and the vast body of Le Mayeur’s work, from the ‘20s to the ‘50s, is fading away behind glass on every wall.

It would have been nice to clearly see the artist’s vision of his muse from every conceivable angle, but somehow I found the decay pleasantly, ah, decadent.

Everywhere were shadowy images of Ni Pollok carrying water, topless, or dancing, topless, or fetching water from the well, topless. Here and there, for balance, a fading seascape painted in Turkey in 1921. I stood where the old boy had his easel and imagined I saw what he saw.

Le Mayeur died in Brussels in 1958 while seeking treatment for an ear cancer, having already, fearing the worst, cut a deal with Sukarno’s cultural minister to turn his home and studio into a museum.

But Ni Pollok was given lifetime residence and the job of managing the museum. She turned the lounge and garden terrace into a party zone, and through the next couple of decades hosted some of Bali’s most chic private dinner parties, until a delegation from the ministry of culture, fearing that revelers might damage the art, asked her to cease and desist.

I realised, casing the joint as we left, that when this salon was at its height of fame in the 1970s, my mates and I used to park our bikes about 100 metres from its entrance, just outside the walls of the hideous Bali Beach Hotel, while we surfed the long rights of Sanur Reef. So near, and yet so far.

Enough of all this culture. Surf’s up and we’re heading down the coast.