Like quite a few in the audience at Noosa Regional Gallery, I came for the dolls and stayed for the cultural lessons of a somewhat confronting, but richly rewarding, three-way exhibition.

All three of the elements of the exhibition that opened at NRG last Friday involve First Nations’ themes but in vastly different ways.

Because I’d written about Sarah Midgley’s compellingly awful and awfully compelling Budgeree dolls, I was intrigued to see them in the flesh, as it were, but this turned out to be a curtain-raiser for two quite stunning exhibitions of magical realism.

But first the dolls.

Created by Sarah Midgley in her old age in the 1920s and 1930s, the Budgeree dolls reflect distant memories of a childhood at Mill Point on Lake Cootharaba in the pioneering 1870s, where the little English girl made friends with the Kabi Kabi children of the area.

These reflections also resulted in a children’s book called Picanninie’s Yabba Yabba, lost in the dustbin of history but rediscovered and brought back to life by historian Dr Ray Kerkhove and launched in absentia (still at the printer) at the gallery on the same night.

Sweet in its sentimental memories of childhood friends, the slim volume uses the language and racial attitudes of the time with sometimes shocking effect, but not as shocking as the dolls themselves. They reminded me of the golliwogs that were still around when I was a kid, crude and offensive caricatures of African and African-American stereotypes.

But as a launching pad for the works of First Nations artists Michael Cook and Fiona Foley, the Budgerees certainly did the job.

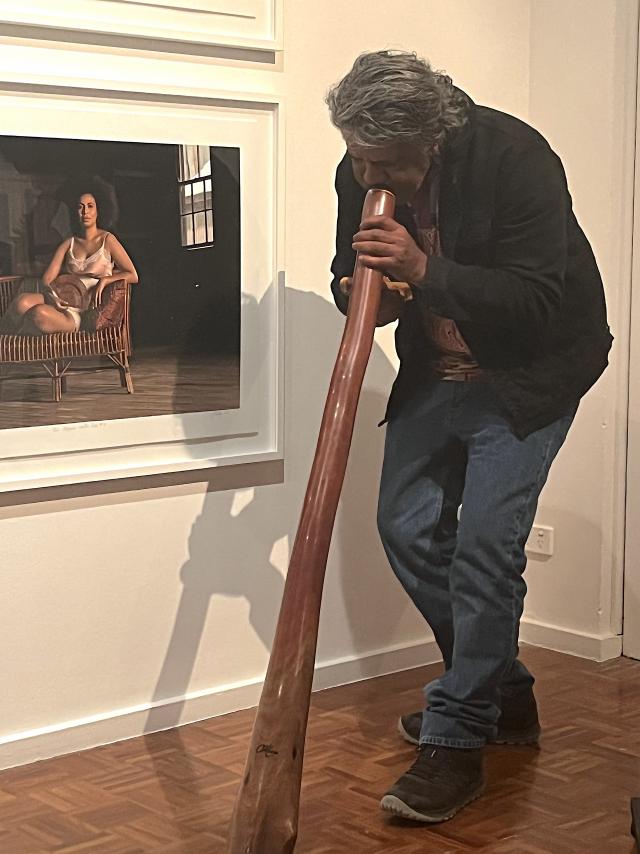

Cook’s Natures Mortes is a series of photographic works that uses a homage to the Dutch Masters to subtly explore the devastating impact of colonisation on First Nations’ peoples, his narrative broadening to encompass the global repercussions of environmental degradation.

As writer Louise Martin-Chew observed in launching the exhibitions: “Michael has looked to the traditions of the Dutch Masters to engage us in the fundamental differences between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people, reminding us that the traditional knowledge of the land might help us avert some of the environmental challenges we face.”

Acclaimed Badtjala academic and artist Fiona Foley’s photographic exhibition, titled Nguthuru-Nur, was as culturally confusing to me as it was beautifully executed.

As Martin-Chew explained: “Using a tree on Badtjala country that is as old as the Magna Carta as her starting point, Fiona takes us on a journey of cultural and sexual exploitation by white people, among other things, with images that catch the eye with their beauty and create a curiosity to know more. It’s magical realism, playful in the way it portrays such a difficult history.”

Wanting to know more about the complex ideas behind her exhibition, I spoke with Dr Foley after the launch and was directed to her little illustrated volume about Bogimbah Creek Mission and its significance in Badtjala history.

In it she describes the excitement she felt when she was taken to the Magna Carta mangrove tree on the property of Mary River historian and environmentalist Lindsay Titmarsh, and started to see a connection between the historic human rights document and her own culture back then, long before colonisation.

She writes: “I had an idea that my central character would stand between the two surviving trunks of this ancient tree of knowledge… this would be my starting point. This ancient land doesn’t give up her secrets easily, but I reflected on the times when my forebears walked this way in a utopia I can only dream about, hey.”

In his opening remarks, gallery director Michael Brennan gave a sensibility warning but also thanked First Nations’ peoples for their participation.

“Within this work there are very important messages that tend to sneak up on us, but there is also work that, by today’s standards, is offensive.

“But generously over these three exhibitions we are being given the opportunity to think about the ideas presented and reflect on how we can increase our understanding of what is often an uncomfortable and ignored shared history.

“If we don’t make space for these stories to be told, I believe we’re complicit in excluding them.”

The three-way exhibition will be at the NRG until 4 September. Don’t miss it.

And extending these ground-breaking solo exhibitions outside the gallery walls, First Light will showcase photographic and video work of some of Australia’s most exciting First Nations’ artists, and feature evening projections peppered amongst the natural and built environments of Hastings Street as part of the Noosa Alive festival. Featuring the work of Michael Cook, Fiona Foley, Kent Morris, Lyndon Davis with Leah Barclay and Tricia King, and Peta Clancy and Helen Pynor, First Light runs from 28 to 31 July.

For more information, visit noosaregionalgallery.com.au/