When the completion of a map of colonial frontier massacres around Australia was announced last March and I discovered that the alleged massacre of Kabi Kabi men at Murdering Creek on Lake Weyba in the 1860s was on it, I was excited to learn what compelling new evidence the team of academics had found.

Alas, the exhaustive, eight-year University of Newcastle study, titled Colonial Frontier Massacres 1788-1930, backed its claims to be the “first sustained effort to break the code of silence”, with the same solitary piece of evidence that the Queensland Anti-Discrimination Commission had rejected as hearsay five years earlier.

The new “massacre map” claims that the Murdering Creek massacre did happen, between 1 February and 30 April 1862, killing 25 Kabi Kabi and zero “agents of the state”, and even names the key perpetrators, citing as its lone source Ray Gibbons’ 2015 paper Deconstructing the Myth of Murdering Creek.

Gibbons’ paper is a fine, detailed and scholarly work that contextualises the alleged massacre in a way that makes it easy to believe that the combination of elements – repeated harassment and violence against the Traditional Owners by Native Mounted Police, Kabi coaxing livestock into the shallows of the lake and killing it for food, hot-headed, teenage station managers patrolling their properties like gunslingers and frequently taking pot-shots at Kabi hunting parties – could easily have led to such a massacre, but the only proof offered by Gibbons in the first instance and Professor Lyndall Ryan and her team at UNC in the massacre map is the 1982 posthumously-published account written by DW Dave Bull based on a letter he had received from a man named William Low in 1944.

Low, who was not alive at the time of the alleged massacre, wrote: “Re Murdering Creek I should certainly say Chippindall… was at the head of the Murdering Creek gang.”

When Dave Bull used the letter in his book, Short Cut To Gympie Gold, he took Chippindall’s name out – possibly because the teenage station manager in 1862 had become the nine-term chairman of the Widgee Division later in life, and the patriarch of an important landholding Mary Valley family. He also embellished his account of the massacre with colour that seems to have come out of Tewantin pub yarning, which was known to be his hobby.

None of it seems to constitute the significant historical evidence that the map-makers say is required before putting it on the massacre map.

The actual narrative entry for Murdering Creek is: “Walter Taplock Chippindall, manager of Yandina Station, Richard Jones, sen. stockman John Farquarson and four other men ambushed and killed about 25 Gubbi Gubbi men fishing in canoes at Murdering Creek, Lake Weyba, during the bunya season (Gibbons 2014, pp 142-7; 282).”

Chippindall’s christian name was William and his middle name was actually Tatlock (known as “WT”) and in his many years as a property boss in the Mary Valley he was highly regarded by the First Nations’ people who worked for the family and camped on his land. Which is not to say he wasn’t a teenaged murderer, but there is no serious proof.

Anyone who has researched the events surrounding Murdering Creek – and I count myself in that group – would dearly love to know what really happened, but I think it’s counter-productive to hang Chippindall’s memory and legacy out to dry on the flimsy say-so of Bull and Low, particularly when it’s done in the context of a ground-breaking digital technology study of high academic authority.

So I took myself off to last month’s AIATSIS Summit to hear the esteemed digital humanities expert Dr Bill Pascoe, the system architect of the massacre map, explain how the evidence was assessed.

He said in part: “We didn’t expect the scale of the project to be so large, but each massacre had to be identified and then researched.

“We did it in stages, state by state. My involvement was as digital software developer so I might not be able to answer specific questions about the history, but what I do know is not just technical, but about learning how to translate the information into software.

“We know that there were probably more massacres than are represented on the website, but there’s just not enough historical evidence to put them on the map.

“One of the purposes of the website is to present a convincing argument that is difficult to question, and to educate Indigenous people about truths that need to be acknowledged.

“So although the details are sometimes obscure about precisely where a massacre occurred or how many people were involved, there can be little doubt that the incidents presented on the map actually happened.”

Except, apparently, for Murdering Creek.

At question time I asked Dr Pascoe what actually constituted “significant historical evidence”.

He answered: “Well, I’m not a historian but a lot of the evidence comes from newspaper accounts at the time, court cases, settlers’ journals and so on. At the end of the day it comes down to the decision of the historian who is researching it. It often boils down to, are you more sure that it happened than not?”

Or, as we know it in the world beyond the halls of academe, guesswork.

As disappointing as I found the specifics of Murdering Creek’s inclusion, none of the above is to denigrate the concept of the Colonial Frontier Massacres 1788-1930 digital map.

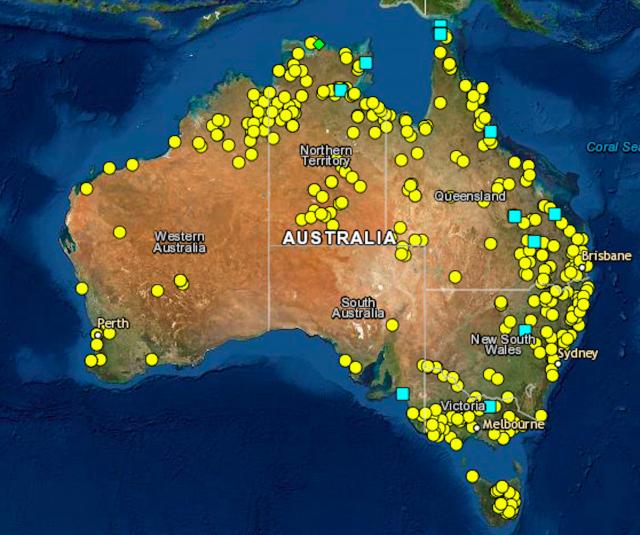

It is an important tool for truth-telling, and I am sure that over time and with a lot of feedback like this it will offer us an accurate map to better understand the tragedy of the 416 massacres on the map, 409 of them against Aboriginal people for a loss of more than 11,000 of their people, with more than 50 per cent of these caused by police and other “agents of the state”.

It’s a history that, black and white, we all need to understand as we move forward. And it has to be right.