PRECEDE

A field day at Theodore in the Central Highlands region reinforced the changing attitudes to grazing and land care. ERLE LEVEY speaks to those at the event about the gains being made in productivity as well as sustainability and a healthy lifestyle.

BREAKOUT QUOTE

“Such an important part of being on the land is bringing the production of food back into the conversation and not just treat it as a commodity.”

If the question was why a 4WD convoy of 20 vehicles was needed to facilitate a “paddock walk” … then the answer was provided at a Central Queensland Landscape Alliance (CQLA) field day near Theodore.

Hosted by Karen Smoothy of Tipperary station, the field day saw more than 90 attend the event, one that primarily looked at a chemical-free solution for tick and weed control.

Supported by RCS Australia, it showed the level of interest there is in regenerative farming in Central Queensland.

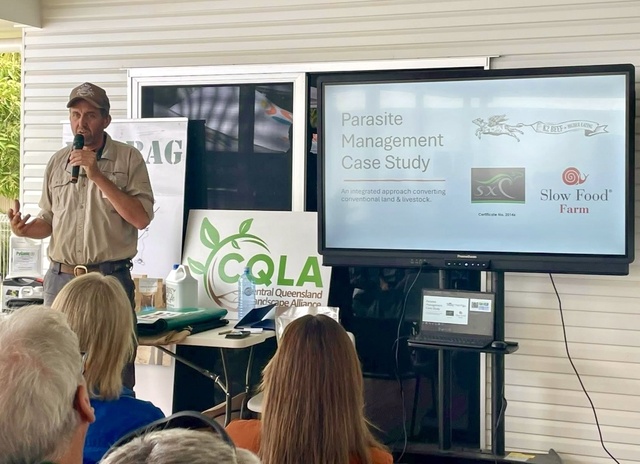

Healthy Herds, Healthy Lands – Innovative Parasite Management was a hands-on workshop for producers who came from Goondiwindi to Wandoan, Monto and all through Central Queensland.

Among the guest speakers was Tim Scott of Kandanga Farm Store in the Mary Valley.

RCS advisor and coach Henry Hinds shared his experience in property management and grazing systems as well as acting as MC.

CQLA joint secretary and 2024 Nuffield scholar Claudia Benn of Arcadia Valley was among those who attended.

Tim Scott, who runs Kandanga Farm and K2 Organic Beef along with The Kandanga Farm Store with his wife Amber Scott, has been at the forefront of integrated pest management for parasites in cattle. The Kandanga Farm Store was the first operation in Australia to be accredited as a Slow Food Farm under a world-wide initiative to create the largest global network of farms dedicated to producing good, clean and fair food in a way that’s rooted in agroecological principles.

Aligned with Slow Food International’s philosophy that everyone deserves access to nourishing food that supports communities, honours the Earth and strengthens local economies, these farms embody the future of sustainable agriculture.

The Theodore field day was presented with an introduction to non-chemical products on the market, including developments in homeopathic products and biocontrol agents.

As well as introducing grazing and other management strategies to reduce parasite load, the day included a property tour and discussion. This provided the chance for those in attendance to share their thoughts and learn from others.

What stood out was that despite marked differences in the features of the land and the climatic environment of the Mary Valley and Central Highlands regions, there were perhaps surprising levels of similarities.

In particular, both regions share a common issue of parasites impacting stock with the tick line being north of Taroom and west of Alpha.

While the Mary Valley enjoys a sub-tropical climate, reliable rainfall and rich alluvial soils, the Central Highlands are more inclined to have variable rainfall, but can experience high-intensity rain events that can lead to soil erosion.

The primary soil type is self-mulching grey cracking clay soils, commonly called black soils.

Water conservation or improved usage is a prime concern in the areas – from Clermont in the north to Arcadia Valley in the south, from Biloela and Theodore in the east to Springsure in the west.

The search for a chemical-free solution for tick and weed control set beef producer Karen Smoothy on a regenerative agriculture path.

The tragic loss of her husband, Wayne, was the driving force to drastically cut down chemical use from her Simmental-cross breeding business.

Karen sought a sustainable approach to control weeds, significantly reduce ticks and confidently navigate drought.

The change in the 1800ha property has been dramatic.

Henry Hinds manages a time-controlled grazing system on 3425ha at Dukes Plains, using the RCS grazing principles. The property is certified organic and used to trade organic and conventional dry cattle.

Tim Scott has tertiary qualifications in Science and Rural Management, and a passion for regional business development.

He has training in Holistic Management, Livestock Trading (KLR), Low Stress Stockhandling (LSS), as well as being a graduate of RCS’s Grazing for Profit program.

As well as working on his own properties, Tim has worked internationally in livestock and equine industries, and been the driving force behind several fast-growing agribusinesses over the past two decades

What has stood out about the Central Highlands in recent years has been the increase in properties adapting to ground cover, even large pastoral companies.

“It was a good turn-out at Theodore,’’ Tim said. “There was genuine interest in the topics, particularly the reasons to get rid of poisons.

“There were a number of conventional graziers in attendance looking to reduce or eliminate chemicals.

“You would expect a big jump towards regenerative or organic methods.

“There was a passionate talk from Karen (Smoothy) that made everyone sit up and listen.’’

The motivation behind the change in the philosophy at Tipperary over the past 10 years has been: “To build a strong ecosystem on our land and to raise healthy, fertile cattle. To create a life where we are happy, healthy, and financially independent with time to enjoy family and friends.”

At the heart of this vision is a guiding principle to avoid chemicals wherever possible.

“Tipperary has been in the Smoothy family for 50 years.

For the first 40 years of these 50, we followed the management system of set stocking.

“Paddocks were grazed continuously, with occasional rests.

“Bulls ran with the cows year-round.

“Weaning and branding happened three times each year.

“Dipping for ticks was a standard part of management.

“These practices suited us at this time, especially since the earthmoving business took priority.’’

The turning point came in June 2015 when Wayne passed away, after suffering the effects of misuse and prolonged exposure to chemicals considered harmful.

That devastating event gave Karen the determination to minimise chemical use across every part of the operation, and to ensure that

when chemicals are required, they are used with care and safety.

Karen started researching, speaking with locals and exploring how to become as natural and organic as possible without compromising cattle health. They merged five breeder mobs into one and treated the herd with Acatak three times in a period of a year.

After treatments, cattle went into paddocks that had been rested for 3–4 months in the growing season 4-5

months in the non growing season.

At that time, there were 13 paddocks.

Steps taken since 2016 included the introduction of rotational grazing with the aim of eradicating ticks.

There were nine dams, one paddock trough and a creek.

By 2020 that had changed to 19 paddocks including lanes, three paddock troughs, the creek and a bore.

Today there are 55 paddocks, the nine dams, and 21 troughs – excluding yards.

“We are looking forward to increasing paddock numbers in the future.

“Our water system is pretty much completed with only two troughs to go. So far, we have installed 20 new troughs and a bore.

“No animal walks more than 600m to water now.’’

In the non-growing season, the paddocks are rested from 90 to 120 days, and in the growing season 45 to 90 days.

A water system and cell grazing is in place.

Branding and weaning takes place once a year and the herd has not been dipped for nine years.

Karen admits to now having a good knowledge on how to match stocking rate to carrying capacity, and a full understanding of plan, monitor and manage.

This has been enabled through RCS and the MaiaGrazing pasture management software system.

In doing so, soil health and biodiversity is improving, along with ground cover.

The result is quiet, healthy cattle and increased carrying capacity, along with limited use of chemicals.

Electric fencing finds cattle respecting just one wire, and the paddocks are easier to muster in.

At Tipperary, Karen is planning to install more temporary electric fencing to maximise stock density for minimum time, but also more permanent electric fencing.

DESIGNED TO SHARE KNOWLEDGE

The Central Queensland Landscape Alliance (CQLA) is a volunteer-led network that connects landholders, industry, and community to share knowledge and champion regenerative agriculture across Central Queensland.

Through peer-to-peer learning, field days, and collaborative projects, CQLA supports producers to adopt practical, locally proven solutions that enhance soil health, biodiversity, and business resilience.

For Claudia Benn, who shares the role of secretary with Kylie McTaggert, the Theodore field day brought increased knowledge and energy.

Claudia and partner Miles Burow work on the 3755ha Benn family property, Mount Kingsley, in Arcadia Valley.

As a qualified agronomist, Claudia splits her time between consulting in the areas of broadacre cropping and grazing management for FARM Agronomy and Resource Management.

Mount Kingsley is an organic, grass-fed beef breeding operation and Claudia is passionate about improving economic, ecological and social outcomes of agricultural systems.

She intends to do this by farming in alignment with natural processes and addressing environmental challenges through identifying root causes.

“I place a strong importance on deepening our ecological literacy, encouraging diversity and cultivating biological relationships between soil, microbes, plants, animals and people.

“Having been awarded a 2024 Nuffield Scholarship I plan to explore how we can profitably farm more in alignment with these relationships.’’

Claudia is the third generation to farm Mount Kingsley, since her grandparents Owen and Mary Benn drew the block in the early 1960s.

Since then David and Chris Benn continued the work on infrastructure and a desire to work with the environment for a sustainable production system.

Now Claudia and Miles are tackling the sustainability challenge further.

The Theodore workshop highlighted methods of integrated pest management, Claudia said.

“But there is no silver bullet. Instead we need to layer the approach.

“That includes nutrition – and there is a need for vegetation diversity.

“It’s important to understand the importance of what we select for … as an example, selecting for tick and fly resistance can mean we select against fertility.

“There was really good discussion on taking a holistic approach, and there is the example of the amount of birdlife.

“If you are to create good a habitat for birds then you are working with nature.’’

A Biloela field day earlier in the year provided the stimulus for the recent event.

That event included the importance of dung beetles and worms in the soil.

“It stemmed from that,’’ Claudia said. “There was a lot of interest in the impact dung beetles made on tick and fly numbers as an integrated approach.

“People wanted more.

“Such an important part of being on the land is bringing the production of food back into the conversation and not just treating it as a commodity.’’

As a 2024 Nuffield scholar Claudia was part of a study tour that included Canada, France and Georgia.

In her Adelaide address, Claudia said that while working as an agronomist she heard the saying that we’re constantly trying to kill the things we want to live, and keep alive the things that want to die.

“At times you wonder why farming is not seen as a fight against nature. Is this not the definition of unsustainable?

“Trying to find a balance between ecosystem health, productivity and profitability felt like walking a very fine line and a constant trade-off.

“I felt that nature was fragile and always crumbling around us. Yet this led to my biggest realisation in the past couple of years, that maybe nature isn’t actually fragile and maybe that it is inherently resilient.

“Certainly constant pressures over time – whether they be environmental or human induced – are absolutely degrading our ecosystems.

“But the more I looked and observed then the more I found traits that actually build resilience.

“There are global examples of people who have built these traits into their personal lives, their businesses and their farming systems to also build resilience.

“Nature is adaptable and ecosystems are never static. They are constantly responding and adapting to the pressure applied.’’

Claudia believes nature is incredibly complex and diverse and that these come together to create an inextricably linked web.

Livestock nutrition is one example of the incredible complexity of biological relationships.

Quoting Dr Fred Provenza from Utah State University, Claudia said decades had been spent researching nutritional wisdom.

This refers to livestock that will self-select plants based on their individual nutritional requirements, but they will also select plants in order to self-medicate.

In the French Alps, Claudia met shepherds who have been using experiential knowledge for thousands of years in their herding of sheep.

This gives an incredibly in-depth local knowledge in which to work with the complexity and the diversity of their environment.

The shepherd values the relationship between the landscape, the plants and the livestock. They are always observing the physiological and behavioural signs of their flock, and then adapting the grazing route.

In Georgia, a country at the intersection of Europe and Asia, farmers displayed a rich tradition, culture and connection around wine production – particularly of their 8000-year-old techniques of fermenting wine buried in clay vessels underground.

Claudia said that in mid-western Canada, farmers Derek and Tannis Axten were witnessing the downfall of rural regions due to larger machines, less people and the prioritisation of efficiency over community.

The Axtens don’t want to be wasteful but believe they shouldn’t base everything on efficiency.

In their province of Saskatchewan, they are building community into their farming system and have done this by investing in an on-farm grain grading and flour mill facility.

This has allowed them to shorten their supply chain, and value-add with traceable and nutritious products to consumers. This increases job opportunities and builds regional industry.

From her study tour Claudia has learnt that nature is far more complex and intelligent than we could comprehend .

“Honestly, what a humbling and wondrous thing that is.

“As farmers we know the importance of building business literacy and practical skills, but are we valuing and investing in building our ecological literacy?

“I learnt so much from visiting all these farming systems around the world but I now feel really motivated to slow down and to really look and listen, smell and feel, and get to know our system intimately.

“Then get creative with management systems or practices that can better work with the complexity and diversity of our environment.’’

At the outset of Claudia’s journey she had a mindset that farming was about scarcity and competition.

Now she suspects the real power in building resilience is in nature – that it is a matter of fostering a connection between community and soil.