“What we really need to understand about the issues facing the North Shore and Cooloola is that the vast majority of people who go there are not hoons. They’re just normal people looking for a wilderness experience. No matter what we think of what the place has become, for many urban dwellers it’s a frontier, and it’s the only one they’ve got.”

So says former Noosa mayor Noel Playford, whose idyllic memories of a childhood spent fishing, hiking, paddling and adventuring on the pristine river, the swampy crab holes, the dunes and the endless lonely beach, stretch back more than 70 years, and nearing 80, he knows better than most that the gap between the dream and the reality is like quicksilver.

In this article, we’re going to look at what the future might hold for the North Shore and Cooloola, but sometimes it’s instructive to look back as you move forward.

There was no ferry across the Noosa River when Noel was growing up on his parents’ farm at Kin Kin in the early 1950s, but there were two ways to get to the wilderness.

He recalls: “It was all state forestry in those days and from our place you’d head up the Wolvi road and turn right at the forestry camp. They called it Cooloola Way later, but then it was just a track, and it was the only way to Rainbow Beach before there was a town there.

“You were supposed to get approval to use it but no one ever did. We’d camp there at the headwaters of Tin Can Bay and spotlight for crabs at night, wading knee-deep through the mud in bare feet.

“Further along we’d cross the bridge at Teewah Creek and head down what was known as the military road, later renamed King’s Bore Road, onto the beach. You could get down it OK but getting off the beach was difficult, particularly if the sand was very dry.

“I’d try to get a ride with the uncle who had the light ex-army Jeep rather than the one with the Land Rover, but either way it was a long, slow process.”

The other way to the beach for a fishing trip was to hire a boat at Boreen Point and, from Teewah landing, wade through a couple of hundred metres of swamp to the beach track and find a gutter to fish. Noel recalls seeing occasional ancient Fords and other relics that had been converted into beach cars.

“The people who had shacks along the beach would float them over from Tewantin and keep them on the North Shore, and apart from replacing the battery, they seemed to last forever.”

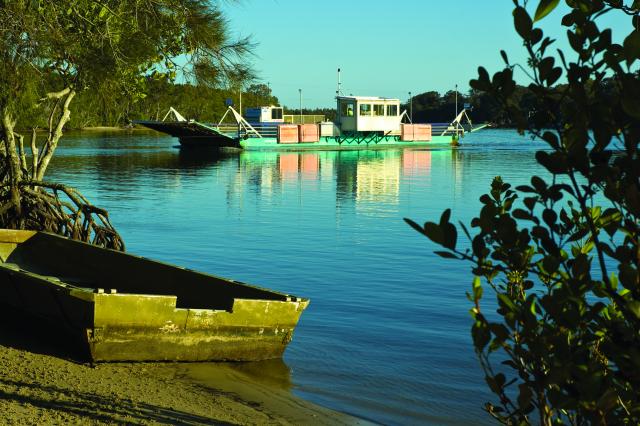

In the early 1960s the winds of change began to sweep along the North Shore beach. First, a man called Herb Woods set up a ferry service at the end of Moorindil Street in Tewantin, running a raggedly intermittent service on a tiny barge without council approval.

“One night we missed the last ferry,” Noel Playford remembers. “I had to swim the river and wake Herbie up to come and get us.”

Second, the state government cleared all the old fishing shacks off Crown Land behind the beach and subdivided 48 blocks at Teewah and offered leases to the shack people and Noosa residents.

Newly-wed teachers Noel and Diana Playford bought a block and started building a weekender.

Says Noel: “The ferry was the beginning of the end of the good old days, which I’d loved, except perhaps the sand that got into everything when you camped on the beach – your bed, your clothes, your hair, your teeth, your food. But you could be up there for days and not see anyone but the occasional wormer.

“The ferry and the Teewah subdivision made it possible for people like us to spend weekends and holidays there, but it began to change. We started to see more traffic on the beach, and it went from being just a few fishermen in old road cars, to modern four-wheel-drives, and it started to get busy. Or so we thought.

“But there were years when the beach got eroded down to coffee rock and it was difficult to drive, and that was when people started talking about building a proper road to Teewah. They wanted electricity too! What they really wanted was suburbia in a wilderness.”

The early 1960s were still a bit like the sleepy 1950s in Menzies’ Australia. The wave of social and political revolution amongst the young that would define the decade had not yet washed onto our shores, and in Queensland, the tide had recently turned the other way with the 1957 ousting of Labor after decades and the election of the Country-Liberal Party.

The new conservative state government quickly introduced the Crown Land Development Act, creating opportunities for huge development leases over large slabs of coastal land, and by 1962, with the completion of the Bruce Highway between Brisbane and Cairns, the bulldozers were busy creating link roads to new towns and resorts, and the government was counting its takings and its rapidly improving approval ratings.

But there were some who wanted the brakes applied.

In 1962, a poet and a painter came together when friends Judith Wright and Kathleen McArthur joined with a publisher and a naturalist to found the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland in Brisbane, while later in the year in Noosa, the foundation meeting of the Noosa Parks Development Association was called by Arthur and Marjorie Harrold. (The association later dropped development from its title and within three months it had more than 100 members).

The political battle to save the sand mass of Cooloola began in 1963, with the state government declaring a 16,000-acre fauna reserve stretching from the upper reaches of the Noosa River over the Cooloola Sand Patch to the ocean. This sacrifice of a tiny piece of poorly-timbered country was seen by conservationists for what it was – tokenism in the face of pending lease applications for sandmining and logging operations.

The Parks Association countered by calling for the creation of a national park extending from the Noosa North Shore to Fraser Island, taking in the Coloured Sands, the Cooloola high dunes, the lush rainforests, perched lakes and the Noosa Plain. A huge call, but this was a prized and treasured environmental asset. The battle lines were drawn. A few months on, sandmining companies applied for two leases over 6000 hectares of the high dunes.

By the end of the 1960s, alongside the 300-strong Noosa Parks Association stood the Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland, the National Parks Association of Queensland, the Australian Conservation Foundation and at least another dozen smaller conservation and community groups.

The NPA teamed with Kathleen McArthur on a huge Postcards to the Premier campaign that resulted in more than 150,000 cards reaching the desk of new Queensland Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen, an achievement Arthur Harrold called “a masterstroke”.

In 1970, NPA, the Brisbane-based Cooloola Committee, and the Fraser Island Defenders Organisation put together a petition of 24,000 names in support of a Cooloola National Park, most of them drawn from marginal seats, and provoked a backbench revolt that threatened Joh’s premiership.

He reversed his pro-mining stance and supported protection of the dunes, although he also spent the next couple of years securing perpetual water extraction licences from Teewah and Seary’s Creek within the park, and their threat to the ecological integrity of the Noosa River system is still very much with us. But after its declaration in 1975, the Premier and his secretary, Beryl, took the government jet to Rainbow Beach, and Bjelke-Petersen actually wept at the beauty of the dune-scape he believed he alone had saved.

The gazetting of a 25,000 hectare Cooloola National Park was a massive symbolic victory for Queensland conservationists, but the Parks Association and its allies knew there was still much to be achieved before the sand mass could truly be considered safe.

Nearly half a century later, and after many vital additions to what is now officially known as the Cooloola Recreation Area, Great Sandy National Park, the threats remain, although their sources are somewhat different.

Says Noel Playford: “In the years I’ve been talking about, we’d do things over there that you wouldn’t do now, but because there were so few of us it didn’t make that much impact. Now, with so many more people over there, it’s become a lot easier to destroy the environment.”

It’s a view shared by many sections of the Noosa community, and the dilemma of people-pressure is reflected on the Queensland government’s website introduction to the park: “Chances are, if you’ve heard of Cooloola you might know it as the sandy beach highway between Rainbow Beach and Noosa, the mecca of four-wheel drivers and fishers. But there’s a lesser-known side to Cooloola Recreation Area, Great Sandy National Park. Get off the well-worn coastal track and you’ll find a vast landscape of sand dunes, freshwater lakes, tall forests, paperbark swamps, wildflower heath and a pristine river system.”

The unwritten subtext here is, “Give the beach a break!”

Veteran Noosa councillor and planning and sustainability consultant Brian Stockwell has been a member of the Teewah and Cooloola Working Group since its inception in 2018, although since the council elections of March 2020 the group has met only once, which Noosa Today understands reflects a lack of interest from the Gympie end since the election.

This was by no means the first working group on Cooloola and it won’t be the last, but Cr Stockwell is adamant that over its first two years it achieved consensus.

“Within the working group there was broad agreement that the focus should be on enhancing the wilderness experience, beach camping not beach driving.”

This writer has seen documents that indicate the group had produced a raft of recommendations to deliver that focus before it went into hiatus, including abandoning the one-day beach permit, and reducing the camping capacity of the entire park from over 2000 to around 1300.

But while the group may have slipped into slumber, Cr Stockwell has been proactive behind the scenes, researching numerous response models for the North Shore and more generally for Noosa destination management, some of which he outlined in an article published in July, 2020, in which he posited, “before we can defend ‘The Noosa Experience’, we must first define it”.

He continued: “Rather than loving Noosa to death, we need to understand the carrying capacity of our natural attractions … our river, our beaches, our parks and our trails.

“At what point is the experience of living and visiting Noosa diminished by having to share it with too many people, too many cars or too much loss of the natural values and village atmosphere that brought most of us here?”

Cr Stockwell outlined possible “interventions to defend the Noosa North Shore experience”.

These included capping day permits for vehicles on Teewah Beach, an on-line booking system for the ferry to control congestion and safety issues, a responsible beach driving test attached to on-line permit applications and the introduction of vehicle recognition software at the ferry for ease of payment. While some of these ideas seem complex and even draconian at first glance, it is interesting to note that a number of them are currently under investigation by consultants due to report to Noosa Council on business models for the future ferry lease, and to Queensland Parks and Wildlife on carrying capacity for Cooloola.

Brian Stockwell remains optimistic about the future of the North Shore.

He told Noosa Today this week: “The greatest challenge is the beach. The use of the beach is currently in fundamental opposition to the central ethos of what Noosa is. The Queensland Government has allowed it to become a blemish on the Noosa brand by not controlling and managing the impact of visitation.

“I would be hopeful that the State Government will take a responsible approach, even if it doesn’t understand why it’s so important to Noosa, but just wanted to make the beach safe. These issues are not going away, and when we have Native Title finalised, and when we see the Great Sandy management plan, these are going to be triggers for further changes.”

Noel Playford’s golden age of the 1950s is likely to remain a beautiful memory, but the straight-talking former mayor is also optimistic.

He says: “I’m fairly positive about the future for North Shore and Cooloola, particularly the parts of it that people hardly ever get to. I don’t see much happening to the Sand Patch, for example, because most of the people who go there tend to respect where they are. You go up on the dunes and you won’t find a bottle top.

“It’s totally different on the beach and at Double Island Point. The vehicles have to be controlled but it’s going to be tough. The 4WD lobby is a bit like the American gun lobby. Their attitude is if you start restricting us it will never end, so don’t start.”