The late, great Jack McCoy received a well-deserved Order of Australia in last week’s Australia Day honours list, for “significant service to surf cinematography”.

Not to cast aspersions on Jack’s gong, but the citation is stupendously understated. If you look at the statistics, Jack’s contribution wasn’t just significant, he owns the art form. With 26 surfing features produced and (in the main) and self-distributed between 1975 and 2018, no other surf film producer, in Australia or anywhere in the world, gets close to his output, and no one is likely to ever do so going forward.

And the quality of Jack’s work over more than 40 years puts him right up there at the top of the scale. Put simply, no one has ever worked harder to bring the true essence of surfing to the screen.

I was fortunate enough to be there right at the beginning of Jack McCoy’s illustrious career, in Bali with him and Dick Hoole, his partner in Propeller Productions, frequently in the water at Uluwatu during those seminal seasons of 1974 and ’75, when Bali was still a dream come true. Then, at the end of the decade, I worked on the narration script in the edit suite with Jack, Dick and editor David Lourie on Propeller’s second feature, Storm Riders.

Jack branched out on his own not long after, but he and Dick remained the closest of friends over the rest of his life. Dick was still there to help his old mate as Jack finished his final four-wall tour last winter, as was I at Nambour, the very last show Jack did, just two days before he died.

I was looking back over my Jack files last weekend, hoping to find some material that defined Jack as a cinematographer and photographer. I couldn’t go past the Millennium Wave.

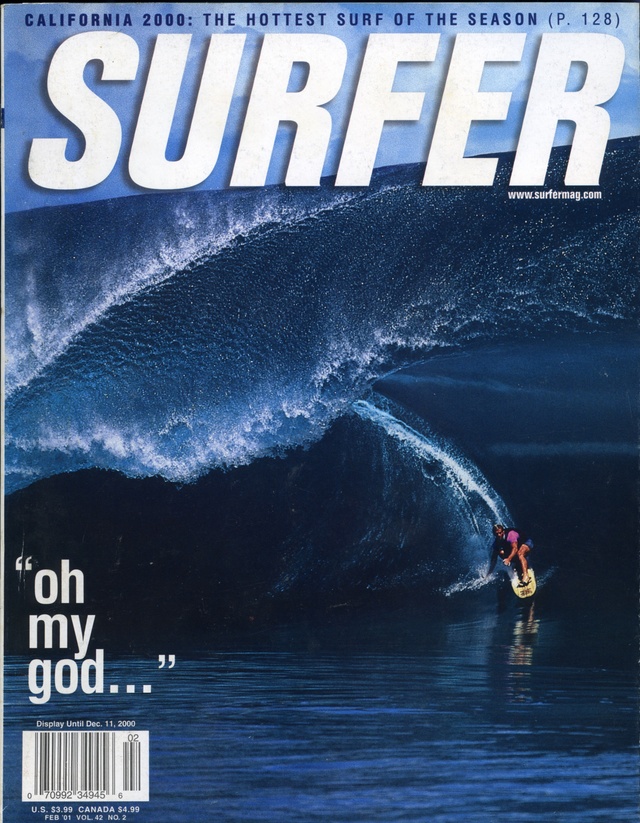

On 17 August, 2000, big wave legend Laird Hamilton set off from the boat ramp at Teahupoo in the dark at 4.30am, with his tow-in team and a posse of photographers and cinematographers, hoping to surf the ultimate day at the famous and ridiculously dangerous reef break at the end of the road. The swell had been on the rise for two days and was expected to max out that morning.

As the sunrise revealed the magnificent sight of perfect, glassy mega-tubes exploding on the shallow reef, Laird and his tow partner Nelson Kubach took a moment to pray before circling around the lineup to watch and wait. It was a long wait. At 8.30am Kubach positioned the ski for action as a massive set rolled in, but Hamilton called him off, a decision photographer Tim McKenna says probably saved Laird’s life.

The surfers elected to take a break and then reset, Laird now being driven by Darrick Doerner. By the time they did so, Jack McCoy was on the back of Tahitian surf legend Vetea “Poto” David’s jet ski. Jack recalled: “I asked Poto if he’d put me in what he calls ‘the box seat’, at the very end of the deep reef crack, just before the wave unloads onto the reef as a big close-out. I could see that Darrick was about to yank him into a bomb.”

Jack was right. It was a rogue set twice as big as anything they’d seen that morning. In the box seat, Jack aimed his high speed camera and waited. At 11.38am, Doerner towed Laird into the biggest, meanest, most perfect tube anyone had ever ridden.

Jack: “So I’m on the back of the jet ski, got one eye framing the picture, the other watching the biggest, thickest wall of water coming at us and I’m almost haemorrhaging at what I’m seeing. This is not only the craziest thing I’ve ever seen in the surf, it’s the m.ost insane moment I’ve ever witnessed in my life. Gripped with fear, for myself, for Poto and, most of all, for Laird, who with one wrong move is dead, I keep shooting, trying not to shake.”

No more than 20 people witnessed what is still regarded as the greatest wave ever ridden. Only one saw it from the box seat. Jack’s work was all over Surfer Magazine and the footage has been seen over and over again by disbelieving surfers. If AI had been around 26 years ago, you’d put it down to that. But this was real, very real.

We miss ya, Jack McCoy AM.

FOOTNOTE: As I write this column, the Lexus Pipeline Challenger event is proceeding in a mix of huge, clean barrels and onshore junk, but whatever Huey throws at it, some serious consequences for surfers hoping to make the tour cut are going down almost every heat. Full report here next week.