What would you expect from the greatest surf showman of them all but a record-breaking turnout for the final Australian farewell for Jack McCoy at Sydney’s Palm Beach last weekend!

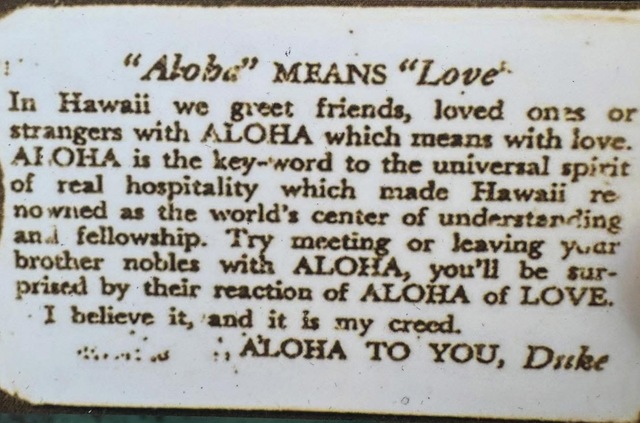

I didn’t make it down for Midget Farrelly’s paddle-out on the same beach nearly a decade ago, but it was Jack, oddly enough, who sent me his drone video of that momentous event. If Jack’s didn’t surpass it, then it was certainly its equal, hundreds upon hundreds of people, from the close circle of family and friends to distant admirers of one man’s legacy and, perhaps more importantly, the aloha he spread throughout our surfing community and beyond.

Led by world champions Layne Beachley, Tom Carroll, Pam Burridge and Mark Occhilupo, and marshalled effectively by Nick Carroll, Maurice Cole and many others, plus the Palm Beach clubbies, the beach farewell was a fiesta of loud aloha shirts, quiet and fond memories, music, dance and a smoking ceremony before the clubbies led the family group out beyond the break in rubber duckies and the rest of us plunged into the icy water and paddled along behind. As Tommy led us through some deep breathing exercises before giving Jack an almighty aloha and the frantic creation of a veil of splashing to send him on his way, I couldn’t hold back another tear for an old mate and colleague who was truly larger than life. Luckily there was so much water flying around that no one noticed.

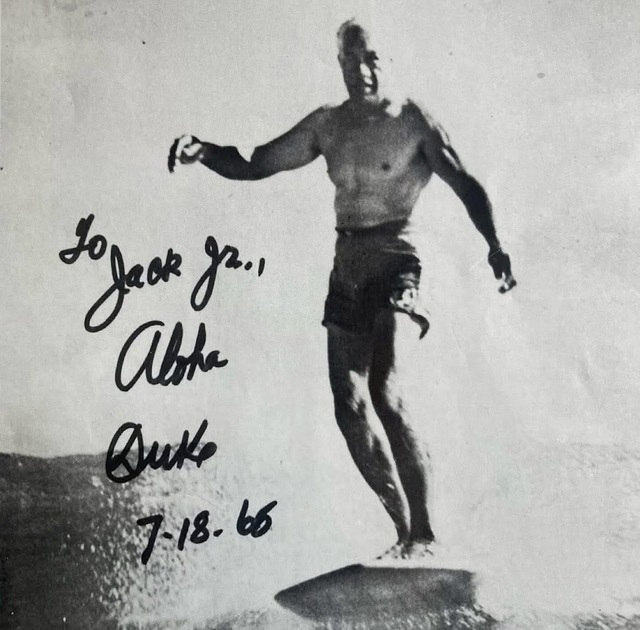

Back home in Noosa on Sunday night, I dug out a folder that Jack had sent me a long time ago, looking for a couple of pictures to accompany this column. But I also found a text he had written for a project we were toying with, about his beloved Bolex and how it nearly robbed us of his unmatched surf film legacy. Here it is in part:

They say your life flashes before your eyes before you die. Right now mine was flashing before me as I lay on the bottom of Hawaii’s famous Banzai Pipeline reef with what felt like the entire Pacific Ocean holding me underwater.

It was the winter of 1975-76 while I was making my first surfing film. My partner Dick Hoole and I had been distributing surf films in Australia when he put a Bolex 16mm film camera in my hands and said, ‘We know what audiences want, let’s make our own film.’

I’d never shot a roll of film until November 1975. We’d taken a crash course on how to run the camera and had bought some great lenses and a water housing before going to spend the winter at the famous home of the biggest surfable waves in the world, Oahu’s North Shore in Hawaii. I’d shot still photos from the water in Australia and Indonesia, however 16mm filming in Hawaii is a completely different deal, especially with a funky and crude plexiglass housing to keep my beloved Bolex dry.

We’d been shooting for about a month when up came a day with Banzai Pipeline’s Second Reef capping and the inside a solid 10-12 feet. Just getting off the beach and out through the rip to where the waves are breaking is an art unto itself. I’d done it many times surfing and bodysurfing, however, with this lump of water housing, the art is multiplied by 10. Once a big set comes through, knowing that this day most of the sets are four waves, I’d run down to the water with my fins on and jump in just as the fourth was breaking on the reef. The water moving to the beach needs to go out somewhere and that’s where I’d head, towards the rip running out next to the break.

I swim with one arm and the other arm holding the water housing which is like driving with the hand brake on. Both legs kicking like crazy, I make it into what I thought was a safe enough position to put my right eye up to the back of the camera and look through the reflex to site my shot. I chose the first wave of the set because Rory Russell, one of the heroes of the time, was taking off. I got my shot and when I looked up, the next wave was much bigger and swinging much wider outside me.

I’d been pulled into the impact zone by the first wave and was now in the wrong spot at the wrong time and about to be caught inside the wave’s lip. The entire force landed about a foot in front of me. With my water housing floating like a cork, I couldn’t get deep enough to avoid the worst of the turbulence, but I wrap both arms around it and pull my body into a fetal position. It seems forever before the wave starts to dissipate enough for me to open my eyes and start looking for some light above me.

Just as I hit the surface and get a quarter-breath, the third wave of the set lands right on top of me and knocks what wind and air I have out of me completely. This time I’ve been pushed into one of the rock valleys of the reef and pinned down face up. I can’t go up, can’t go down, can’t go sideways. But you do what you’ve trained for as a kid. You try to relax, conserve what oxygen you have left.

Then I’m hit by another wave, a surfer’s nightmare known as a two-wave hold-down. I start to panic even though I know it’s the worst thing I can do. The next feeling is actually quite peaceful. You start to go into a dream-like state of surrender. And then I’m floating to the surface with no help from me.

I’m seeing stars as I taste the sweet breath of life. I take another, and then another, and then another. Never felt so good.