By PHIL JARRATT

TIM Brent arrived from Friday prayers in his neck-to-ankle baju melayu and fez and sat down opposite me in the little beachfront cafe that forms part of the modest surf and snorkel camp that he owns with wife Izan.

The day was hot and the sun was well over the yard-arm, so I was into a cold beer. It being Ramadan, Tim should have been fasting until sunset, but he called for an iced tea and said: “You know, there’s a lot of good crap in the Quran, really good lessons for life, but I guess it gets a bad rap in a lot of places.”

I admitted I’d found the scriptures of Islam a bit heavy going, and hadn’t really progressed beyond, the, ah, title pages, and steered the conversation towards more pressing matters, such as the possibility of a little push on the incoming tide later in the day. But later, when I reflected on the exchange, I was struck by the cultural difficulties that must be faced every day by a surfer who grew up in Australia and had not only converted to Islam for the sake of a marriage, but had more recently actively embraced the faith. Not something most of us would take on lightly, but then Tim Brent is not your average guy.

Born in Kuala Lumpur to high profile English expat parents – dad was the chief of police, mum a model and actress – Tim carried the memories of roaming the street food stands of the Malaysian capital and inhaling those intoxicating smells, when both he and KL were small and navigable, through a Sydney education that included a stint at exclusive Cranbrook. In his early teens, he learnt to surf at Bondi, but after his parents’ marriage broke up he found himself a wild child, kicked out of home and living rough on the mean streets of inner Sydney.

Tim went down the usual route of alcohol and heroin that claimed so many in Bondi in the early ’70s, including his friend Brad Mayes, but he had a strong survival instinct that served him well over a couple of tough decades and failed marriages. He would hit the road to surf, find work wherever he could, and start over. This pattern took him to Byron Bay, South Stradbroke Island, Margaret River, Geraldton and Red Bluff (where he was one of the first to surf those powerful Indian Ocean waves).

Eventually, he made a good career in demolition (of buildings, not himself) but a couple of business partnerships ended in tears, and in 1990 he found himself drawn to Asia again. He wanted to surf, but those memories of Malaysia drew him beyond the acknowledged wave nirvana of Indonesia to the Malay Peninsula and the uncertain but uncrowded waves of the South China Sea. He has been there ever since, more or less.

About a decade ago, Tim took up with the high-born Tengku Azizan bindi Tengku Hussain, known as Izan, and after Tim’s conversion to Islam, the couple were married in 2007, just as an opportunity came up to take over a run-down surf camp on beautiful Tioman Island, voted one of the 10 most attractive tropical islands in the world not so long ago by people who keep tabs on such things.

While waiting for a Malaysian Government development grant to come through, Tim and Izan foraged for pippies and clams every day for eight months, selling to the markets for just enough to keep them in rice and petrol for the motor bike. But when the money finally came through, they started work on restoring the Beach Shack at the better end of the island’s best surfing beach, where during the monsoon season a right-hand point break cones alive with long and hollow waves.

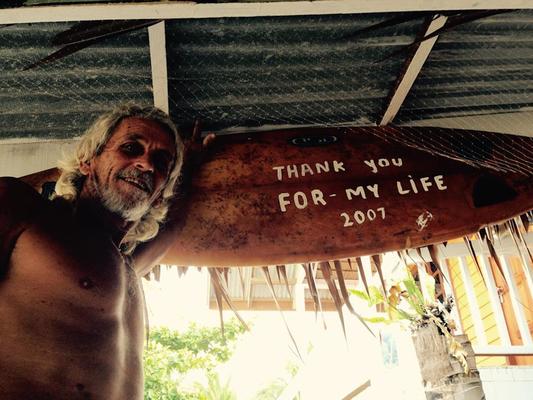

Soon after taking over the Beach Shack, Tim was driving his outboard boat back from a surfing contest on the mainland when both engines blew up simultaneously and the stern disappeared. The boat sank in seconds, leaving Tim to paddle his board for hours through treacherous currents before washing up, exhausted, on a speck of uninhabited island. He made himself a palm frond shelter and drank dew off its leaves for two days until he saw a fisherman on the horizon, drifting down the current. Again he paddled his board for his life, until he got close enough for the fisherman to hear his cries. A day later, he was home. The incident made him think more deeply about his life and where it was going, and while this wasn’t the shining light that led down the road to Islam, he knew that both he and Izan had a lot of emotional baggage to deal with from their former lives, and that this relationship might be their last chance.

Tim started attending the mosque with his wife, and became more involved in village affairs. He started the Tioman Festival, a kind of mini Noosa Surf Festival, with acrobatics and rock climbing thrown in, and he nurtured young Tiomese surfers who are now starting to show potential on the Asian circuit.

The Beach Shack is still a work in progress, a ramshackle piece of paradise on a perfect beach, but Tim seems a happy man. Last Sunday morning we fished an offshore reef until the wind forced us back in. The twinnies sounded very rough, and I commented that I hoped history would not repeat itself and leave us swimming for shore with a bag of fish.

“If it claimed me this time, at least I’d die satisfied,” he shouted above the engines, a big old crease-faced, snaggle-toothed smile lighting up his face.

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win a family ticket to Hudsons Circus](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Hudsons-circus-1-100x70.png)