By RON LANE

WITH total disregard for his own personal safety, the young Australian Charles Snodgrass Ryan, serving as a doctor in the Turkish Army, somehow managed to get his two wounded comrades on to the back of his horse. The first shot through the neck, he placed in the saddle and the second, his leg shattered by shrapnel, he placed behind. Holding the wounded in place with his right hand and leading his horse with his left, he moved out and despite being caught in heavy crossfire from the retreating Turkish Army and the advancing Russians, he managed to join up with his Turkish comrades.

In his book Under The Red Crescent, first published in London in 1897, translated and republished in Turkish in 2005, Ryan described the incident. “The Russians were four hundred yards away pouring hot fire on our retreating troops and our men were answering at intervals, so I was caught between the two fires.” This incident took place during the Turkey -Russo war of 1876-’78.

On 23 October 1926, some 46 years later, this former Turkish Army doctor died. At the time of his death, he was known throughout the nation as Major General Sir Charles Snodgrass Ryan. During the lead up to the Anzac Day Centenary, the media brought us stories of men who became legends during the Gallipoli campaign. Diggers such as Albert Jacka, John Hamilton, William Dunstan and Billy Sing just to name a few, were to become household names.

But one Digger, who served with distinction on Gallipoli and was the centre of an incident which became legendary, has virtually remained unknown. The Digger was Charles Snodgrass Ryan.

Born in Longwood Victoria, on September 20 1853, Ryan was educated at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School. Starting a medical course at the University of Melbourne 1870-’72 he went on to complete his studies at the University of Edinburgh in 1875.

Following this he visited Europe where he undertook postgraduate studies in Bonn and Vienna. However, it was during a visit to Rome that he saw in a copy of the London Times an add that was to change his life forever. Placed by the Turkish Government it was a request for 20 military surgeons. Being young, adventurist and with a thirst for life, Ryan immediately returned to London and following an interview at the Turkish Embassy, was two days later on his way to Constantinople.

As a doctor in the Turkish Army, he saw service against the Servians in 1876 and this was followed by the Russo-Turkish campaign of 1877-’78. It was during this period that as a result of a four-month siege of the City of Plevna, where a garrison of some 14,000 Turkish troops held out for four months against the Russians, that the legend of Charles Snodgrass Ryan was born. Adding to the legend, it was noted that apart from performing his medical duties, he also took part in cavalry charges against superior Russian positions.

While working at Plevna, under atrocious conditions he treated hundreds of Turkish soldiers. Working with the bare minimum of surgical instruments, he was to perfect a fast technique for amputations; techniques which years later in Australia were to become not only the cause for much discussion but also fame and respect.

After many weeks, he was ordered to escort wounded from the besieged city to the city of Sofia. Following this he served in Erzeroum, in conditions that Ryan was to describe as the most horrifying that he had ever accounted. At the fall of Erzeroum he became a prisoner of war of the Russians, but as an armistice was soon declared, Ryan returned home to Melbourne, arriving in June 1878.

According to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, he was in 1879 elected to the honorary staff of the (Royal) Melbourne Hospital as surgeon until his retirement in 1913. Also during this period he was commissioned as a captain in the Volunteer Medical Service. Upon his promotion to the rank of Colonel, he was in 1902 appointed Principal Medical Officer Victoria. Then in 1904 he was the honorary physician to the Governor-General.

Following the outbreak of war in 1914, he became assistant medical director of Medical Service 1st Division Australian Imperial Forces. On his arrival in Egypt in October, he was appointed to the staff of Lieutenant General Sir William Birdwood.

Then came the day that was to add to the legend; 29 May, 7.30am Gallipoli.

In a stretch of earth between the Australian and Turkish trenches known as No Man’s Land, lay the bodies of hundreds of troops, both Australian and Turks. It was agreed that on this day a truce would come into effect, thus giving both sides a chance to bury their dead. After the two days it took to negotiate the terms for the truce, the stench from No Man’s Land was beyond description.

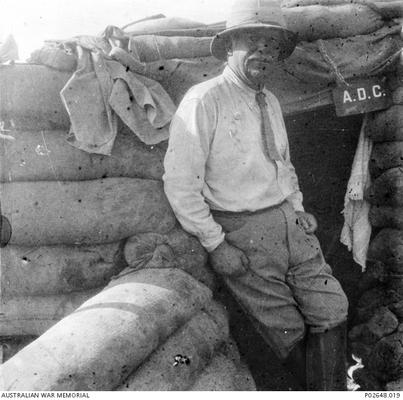

As the burial details went about their duties, some Turks appeared to become very agitated, standing around pointing at an Australian officer, wearing a pit helmet, ribbons on his tunic, and in defiance of the Orders Of The Day, carrying a camera. The reason was that the ribbons worn by the Australian were Turkish. The Turks naturally assumed that the officer had stolen them from the bodies of fallen comrades. This would have to be the ultimate insult; total disrespect.

Moving among the Turks, Ryan who during his service in their homeland had learned the language, overheard soldiers ask, “God knows to which fallen comrades of ours those medals belong. I wonder who he took them from.” Turkish historian Haluk Oral who researched and recorded the incident wrote Ryans reply.

“They weren’t stolen from anybody. They were pinned on my chest because I fought at the siege of Plevna with Ottoman Field Marshal Gazi Osman Pasha.”

“The Turkish officers who had not expected such a reply took a closer look at the doctor and tears welled up in the eyes of the doctor and the officers as well. After a few more broken words were spoken, the Turkish officers tried to kiss the doctor’s hand. Soldiers from both sides looked on astounded.”

In support of his research, Oral quotes newspaper editor Ahmet Emin Yalman, when writing of the incident in 1943. “Soldiers who had gallantly been fighting each other from their trenches came forward and met. It was then that the high ranking officers were astounded to discover a commander wearing the Plevna Medal. How could this be? Everybody listened to his story in disbelief; eyes welled up in tears and Plevna Ryan embraced Turkish officers as former comrades in arms. The indestructible foundation of Turkish-Australian friendship was established there amid the trenches of warfare. These bonds continue today.”

Photos taken by Ryan during the truce, in defiance of the Orders Of The Day, are now a part of military history, and are held for prosperity, in the archives of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra.

Charles Snodgrass Ryan went on to be known as “Plevna Ryan” to the Turks and “Turkish Charlie” to the Diggers. As a result of his devoting an entire chapter to the exploits of Ryan in his work, Gallipoli 1915 Through Turkish Eyes (Turkiye Bankasi 2007) Oral has ensured that at least in Turkey, the legend will never die. Even today the story of Plevna Ryan is told and retold.

For his service to his country and his outstanding contribution in the fields of medicine, he was knighted in 1919.

Major-General Sir Charles Snodgrass Ryan KBE, CB, CMG, VD, died while at sea onboard the Otranto, near Adelaide. He was returning from a trip to Europe. Cause of death was cardiac failure. He was 73.

There is every chance that while on Gallipoli, Ryan would have treated the wounded and shared the hardships and dangers with the old Diggers from our community. Therefore we could also humbly acknowledge this great Australian as, one of Our People.