By PHIL JARRATT

“THE latest advice from our team of meteorologists and the Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre is that conditions are no longer suitable for operations into and out of Denpasar Airport today. We have been advised that Mt Raung continues to erupt and winds are now blowing in an unfavourable direction, and are forecast to continue to do so for the rest of the day.”

That’s the message that greeted me at Virgin Australia’s website last Sunday morning, not for the first time either. Like thousands of others, we are stranded in paradise. Of course, being stranded in Bali is a whole lot better than fleeing the rivers of molten lava in East Java like tens of thousands are currently doing. And Mount Raung, Indonesia’s most active volcano which blows its stack on average every five to 10 years, is only just warming up. But as much as we love being here, life is rolling along without us, and I’m not entirely happy about this.

Already, I’ve blown off the Whalebone Longboard Classic in Perth, where, ironically, I was to have done a video and talk show about my Bali book before all flights were cancelled for Thursday and Friday, and as I write, the wind has changed direction again and from Pantai Pererenan, I can see a grey haze of volcanic ash off in the distance where the airport is normally visible under the white cliffs of the Bukit Peninsula.

We are ticketed out via Perth again, on the only flight we could get on for a week, but with similar winds predicted for the next few days, I can’t see us flying. I’m told the airport is full of angry people sleeping in corners of the tiled floors, but I’m not going near the place until we get a confirmed take-off, and until then we’ll just have to tough it out at the beach.

I’m not expecting any sympathy, by the way, from all of you braving the vicious Noosa winter. I’m fortunate in that most of what I do I can do anywhere, so at my little Bali office beside the pool it will just be business as usual, until it isn’t.

Bali’s surfing pioneer

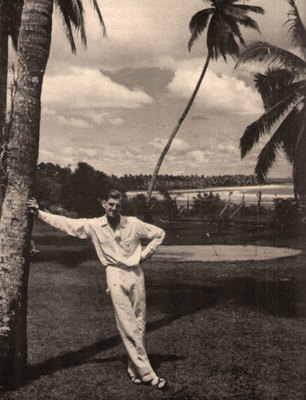

ONE of the projects I’ve been working on over these forced extra days here is some new research on Bob Koke, the American who introduced surfing to Bali in 1936. Although Koke and his wife Louise, who built and ran Kuta Beach’s first tourist hotel in the 1930s, have long since passed on, I’ve managed to establish communication with Louise’s grandson in California, and have also uncovered some new facts about this extraordinary couple.

When she first met Koke, Louise was the wife of the distinguished but drunken and philandering Hollywood screenwriter Oliver H.P. Garrett (A Farewell To Arms, Duel In The Sun). By 1934, Garrett’s affairs had become too much for Louise, who embarked on one of her own, with the handsome tennis coach and stills photographer who often hung around the Garrett’s Beverly Hills estate coaching Oliver and his pals David Selznick and Charlie Chaplin. It may have even been Chaplin, who had visited Bali in 1932, who planted the idea of the island paradise in Koke’s head, but when he stole off with Louise, that was where they ended up, and soon decided to stay.

In her 1942 memoir, Our Hotel In Bali, Louise recalled: ‘We were having drinks on the verandah, and who should show up but a dumpy woman in a sarong, horn-rimmed glasses, black hair, and she spoke English. She rented us a car and … showed us Kuta Beach.’ The woman was the wildly eccentric Britisher Muriel Pearsen, known in Bali as K’tut Tantri, and as a professional troublemaker, but the Kokes fell madly in love with the broad expanse of Kuta Beach and formed an unlikely business partnership with Tantri to create the Kuta Beach Hotel.

Bob had worked in the production department at MGM, where

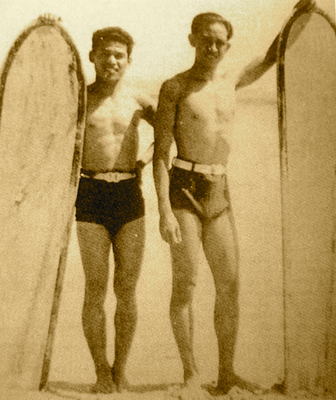

one of his first assignments was to travel to Hawaii as assistant to the director

on the 1932 film Bird of Paradise. Although he had grown up not far from the beach, this was Koke’s first real experience of surf culture, and he loved it. Soon he was riding big redwood surfboards alongside the beach boys at Waikiki. Now, while he and Louise planned their hotel, Bob wired to Hawaii for his redwood plank.

Part of the Kokes’ package was the surfing experience. Bob had recognised immediately the wave-riding potential of Kuta Beach, and even before his own board arrived he carved out a couple of shorter wooden boards in the Hawaiian alaia style, sensibly thinking that they could be used by guests with no experience to ride either standing or prone.

By the end of 1937, the Kokes and K’tut Tantri were at war over a number of issues and she moved into a bungalow on the other side of the sandy beach lane and opened her own hotel, which she also called the Kuta Beach Hotel. The Kokes went to court to try to stop her, and were still in litigation when the Japanese were poised to invade in 1942. Tantri fled to Java, where she became a collaborator with the Japanese, known on the airwaves as “Surabaya Sue”, while Louise took passage for California and Bob joined the US Army, before being recruited to the Office of Strategic Services, later the CIA.

Immediately after the war, Bob Koke returned to Kuta Beach, and found that his hotel had been burnt to the ground. In fact the only souvenirs of those years were his surfboards, which are still in Bali today. When Louise died in 1993, Bob came back to Kuta to scatter her ashes in the waves of the beach she loved, an old man wading into the surf with a small jar, unrecognised by the surfers speeding by him as the father of surfing in Bali.