By Phil Jarratt

ONCE the shock of Midget Farrelly’s death had passed – we knew he was battling a life-threatening illness but seemed to be winning – I resisted putting down my thoughts until I’d seen the avalanche of tributes that came from all kinds of obituarists, from those who had known him well to those who worshipped him but never knew him.

It seemed there was not a lot left to say, but then I began to note the comments on the blog threads and news sites to the effect that this great champion’s passing was that much sadder because he had never been given appropriate recognition in his lifetime. It’s a popular line, trotted out from time to time, but it simply doesn’t weigh up with the facts. I think Midget’s memory and legacy is only strengthened by the truth, so I offer this.

He was a boyhood hero of mine and I knew him personally for 42 years, but I should point out that we were friends for only a small part of that time. I never regarded him as an enemy and I never stopped admiring his skill as a surfer and a surfboard designer, but like a lot of people, I was frozen out of his life for having strayed from his singular vision of how surfing should be, or should be presented.

From 1966 to the day he died, Midget believed that some people sought to deny him his rightful place in surfing history and exalt instead those who had led surfing down the path of drugs and destruction. His resolve to distance himself and his surfing milieu from this was as strong as it was long-lived. Australia’s next great world champion, Nat Young, whom Midget had mentored, was only the most public face of the infidels, who stretched down the line through shaping guru Bob McTavish to the magazine and movie makers of the period to lowly hacks like myself.

From time to time, I found myself secretly admiring Midget’s unbending determination, but I also wondered why he couldn’t forgive and forget. For lesser offenders like myself, there were periods when we were released from the naughty corner. In France in 1998, for example, my wife and I were the Farrellys’ tour guides through the Basque Country, and Midget and I surfed together and shared some good red wine lunches. Midget could be great company.

But by the following year, when I brought him to the Noosa Festival of Surfing for a rematch of the 1964 first world titles final, we were feuding again over some imagined slight.

About a decade ago, at the request of a group of Australian surfers who held the view that Midget had not been properly recognised, I wrote a long article for The Surfers Journal for which I carefully analysed the media coverage of Midget’s competitive career, roughly from 1962 to 1974. I found that for the first few years he dominated it and thereafter shared it with newer heroes, such as Nat Young. There were a couple of mildly questionable opinion pieces, notably John Witzig’s “End of an Era”, but there was no evidence of any concerted campaign to diminish his importance to the sport and culture.

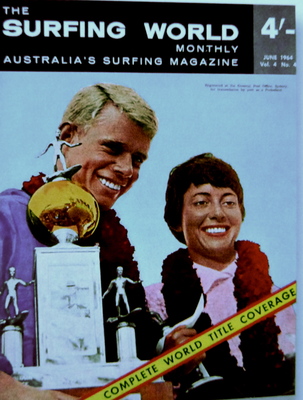

What I did find, however, was that he was unquestionably the dominant competitive surfer of his era, from his win at Makaha in January 1963 to his win in South Africa as a professional in 1970. He won a world title in 1964, and finished a close second in 1968 and 1970. He might easily have won three world titles, but for a claim to greatness, he certainly did enough.

Midget was also a consummate waterman, riding everything from toothpicks to sailboards to side-slippers in waves from waist-high to mountainous, as well as sweeping surfboat crews and rewriting the rule book for riding waves with that cumbersome craft. A complex and difficult man to some, he was also a loyal friend and mentor to many. I wish he’d allowed me to know him better, but I have lasting and cherished memories of those brief interludes when I think he did regard me as a friend.

When we were making our film, “Men of Wood and Foam” earlier this year, I interviewed Nat Young and asked him what influence Midget had been on his surfing. He said: “He was my hero. I wanted to do everything just like Midget.” Nat paused and looked away, I think with some regret that it was more than half a century since they had been close.

Midget also gave an interview for the film (one of his best in years), but only when asked through Mark Warren. When the shoot began he looked at the camera and said: “I’m only doing this for you, Mark. I wouldn’t do it for Phil Jarratt.” His face creased into that famous lopsided mischievous grin and he laughed. It was almost like it had become a game to him.

We’ve lost our first and most revered surfing champion. He will be missed not only by family, friends and fans, but by all who knew and appreciated his invaluable contribution to our sport and culture. Vale Midget.

![[READER COMPETITION] – Win a family ticket to Hudsons Circus](https://noosatoday.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Hudsons-circus-1-100x70.png)