By Phil Jarratt

We shot a lot of great footage of Joe Larkin about 18 months ago for our film, Men of Wood and Foam, but my favourite grab – and the one that gets the best audience reaction – is when Joey is talking about non-existent health and safety in the surfboard workplace back in the day.

He adopts that trademark old rascal grin (one that was never far away) and says: “How we’re not all dead already beats me! Must have been the saltwater cleaned us out, eh?”

Joe’s words were all the more poignant because close friends knew that he had just decided to pull the pin on his cancer treatments and “let nature take its course”. And now, his passing last week doesn’t make it any less sad for those who knew and loved this wonderful character of Australian surfing.

Earlier this year, when I drove down to Cabarita to show him the finished film, Joe was dozing in his chair with a paperback on his lap, out the front of his beloved Besser block “shed”, his mobility scooter with the fringe on top at the ready to whisk him down to the Cabby pub to share the memory of a beer with old mates. But he didn’t have to. I’d brought a couple with me and I uncapped them as we went inside to watch the film.

Of course, Joey barely touched his – just having one in his hand was enough – and I noticed when we got to the Midget Farrelly bit – Midget had passed just a few months earlier – he teared up a little. There was an unspoken moment between us. How we’re not all dead already beats me! And then the grin was back, and he laughed out loud when Scotty Dillon complained he couldn’t get a beer in the nursing home.

Joe was born in Harbord (or “Hardboard”, as the old carpenter pronounced it) in 1933. When the Freshwater headland became a military training area at the start of the World War II, he befriended a young soldier who gave “Little Joe” his Hawaiian-style redwood surfboard when he went off to battle. The soldier never came back, and Joe had his first board at age nine.

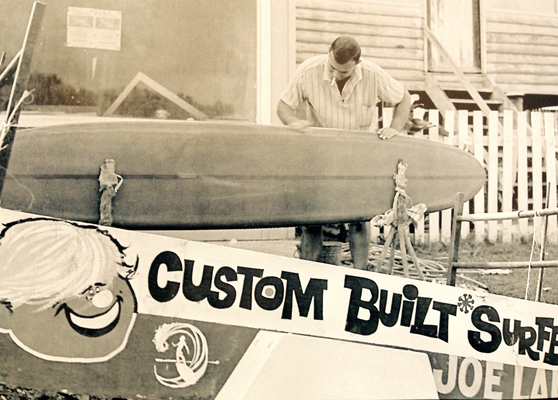

In the late 1940s Joe turned his carpentry skills to the production of plywood toothpicks, and in the 1950s he was in the vanguard of Sydney surfboard production as it transitioned from toothpicks to hollow okanuis to balsa and finally foam. When Barry Bennett opened a factory in the garage of his home, Joe worked alongside him while mentoring a teenaged Midget, but his best work of the early years was done alongside Bill Clymer in Manly, where some of the finest examples of pre-foam surfboards were produced.

Joey always claimed he was a craftsman first and a surfer second, but in the late 1950s he was one of Sydney’s better surfers, as he proved when he finished a creditable third in the 1958 Wanderers Rally at Avalon. Surfing at Fairy Bower also created a bond between him and Bob Evans, Australian surfing’s first entrepreneur.

When Evo decided to make movies, Joe became his sidekick in operating an 8mm movie camera that neither of them knew much about. Joe’s first solo assignment was to film Duke Kahanamoku’s triumphant return to Freshwater in 1956, which he shot from start to finish with the lens cap still on. By 1961, however, Joe was proficient enough to film Dave Jackman’s famous conquering of the Queenscliff Bombora.

The early ‘60s also saw Joe – ahead of the pack once again – move north to the long point breaks and the surfboard-starved masses of Queensland, setting up shop at Kirra for the first time under his own name. Joe Larkin Surfboards became famous for its quality product, but more importantly in Joe’s eyes, the company mentored many of Australia’s future stars of surf and shaping bay. Terry Fitzgerald learnt his chops alongside Joe at Kirra, and later he not only taught the first Coolie Kids – MP, PT, Bugs, Andy Mac – about surfboard design (“by letting them just go for it!”), but often drove them as far as Bells to compete.

Modest and self-effacing to a fault, Joey never sought the limelight, but few people made bigger contributions to surfboard design and surfing itself in those pioneer years.

I remember Joe telling me about judging the controversial final of the first-ever world championships at Manly in 1964. When the final hooter sounded, Joe tallied his scores and found he had Hawaii’s Joey Cabell ahead of Midget Farrelly, but before the judges could hand their sheets in, head judge Phil Edwards, then considered the greatest surfer in the world, told them to mark Cabell down for consistently dropping in. Joey said: “I’d never heard of dropping in! We all shared waves, but this was Phil Edwards, and I was just a bloke from Hardboard, so what are you gonna do!”

DATE CLAIMER: Put it in your diary now! The big Noosa launch party for Life of Brine (the book) is on at Halse Lodge from 6pm on Thursday, 10 August. Film, chat and live music from the Freqs Shannon and OJ. More info next week.