By PHIL JARRATT

Notes from the past

FROM the mountains to the sea, from the surreal to the sublime this week. The sublime was a surprise “karmic cleansing ritual” spa treatment, bunged on by the management of the always-impressive Four Seasons Jimbaran Resort on our arrival just a few hours ago. I’m still tingling from the experience, so more about that next week. The surreal was another trip up into the Batukaru foothills to seek out a tourism pioneer on a hilltop in the jungle.

When it comes to pioneering the hippie trail in South East Asia, the names that first come to mind are Lonely Planet founders Tony and Maureen Wheeler, whose 1975 guide South East Asia On A Shoestring is generally considered to be the first in its field. But in fact a German design student named Hans Hoefer and a hippie known as Starr Black produced a slim guidebook to Bali, aimed mainly at Europeans, in 1970. Hoefer went on to found the Apa Insight Guide series, and I worked with him in 1984 to produce an Australian edition, so he gets a footnote in history, but the man whose long, steep driveway, right next door to Bali’s only silent retreat, I strained up this week is pretty much a forgotten figure in mainstream circles, which is just the way Bill Dalton likes it.

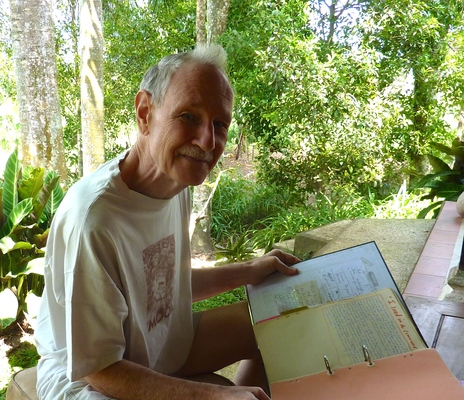

These days, Bill, now 71, is best known for his perceptive contributions to the free Bali Advertiser newspaper, but this lean, likeable, wispy-haired native of Massachusetts, has an incredible story to tell, and as he leads me through the dustbowl of construction work on the rambling home he shares with his Indonesian wife and two young children to his book-lined office, I wonder if he may be reaching the point in his life when it is time to tell it.

Bill got his first taste of travel when he was eight or nine and his alcoholic father would drag him out of bed in the middle of the night and declare: “Come on, Billy, we’re going to New York City!” Perched on his dad’s lap, his little hands on the wheel, Bill would weave delightedly down the turnpike in the night, and more than once remembers standing in Times Square watching the grey dawn, before dad would drive sheepishly home to face the music from mum.

Such frightening adventures could have gone either way for an impressionable child, but in Bill they instilled a desire to roam free as soon as he could. After military service as a paramedic at army bases around the US and in a pretend war in the Dominican Republic, Bill got a university education courtesy of the GI Bill, and managed to wangle his way into Copenhagen University. He says: “The idea of Scandinavia always fascinated me, and when I saw that movie where Danny Kaye sails into Copenhagen Harbour singing, ‘wonderful, wonderful Copenhagen’, I knew where I wanted to go.”

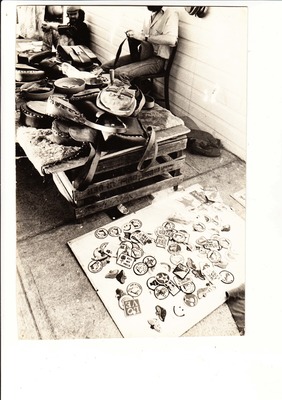

During his college years, he noticed many of his Danish friends returning from adventures in the exotic East, wearing colourful Afghan coats and telling their stories in the coffee houses. So after graduation he used a $1000 inheritance to set out on an overland adventure, taking in Israel, Africa, India, Kathmandu and Burma, before running out of money in Thailand, where he became an English teacher. Along the way he kept hearing about this magical island called Bali, where anything was possible and dreams came true. This became his ultimate destination, but before he got there he had seen more of the Indonesian archipelago than many westerners do in a lifetime.

Part of Bill’s travelling mission was to find something to write about – he was still smarting about the rejection slips he had received for his first failed novel – so he kept voluminous travel notes in a spiral-bound folder. After years on the road, he found himself in a youth hostel in Cairns in 1973, sharing his notes about Indonesia with a couple of German students, when a Kiwi journalist interrupted and told him he should be selling this stuff, not giving it away. The Kiwi also mentioned that there was a hippie arts festival at a place called Nimbin in NSW the following week, and that would be the perfect place to sell.

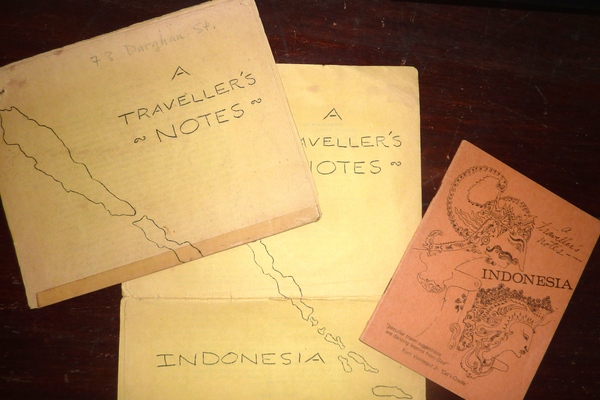

Bill stole into the local library at night to “mimeograph” 800 copies of the six-page document. Then he and the Kiwi jumped on a motorbike and rode the length of Queensland to attend the Aquarius Festival, where he set up on the footpath and sold all of his copies in two days at 50 cents each. On his Bali hilltop, Bill breaks off from his story to find me the yellowed pages of that first edition of A Traveller’s Notes: Indonesia, a rusty staple still holding them together.

As well as providing pertinent details on where to find the best brothels and score dope, Bill’s notes include a wealth of hippie time capsules, like this: “You can sail all over Kalimantan and Sulawesi without bread if you go to ferry captain and say you haven’t any, he will more than likely take you.” Simple as that.

As time went on and the profits got reinvested into the creation of Moon Travel Guides, Bill found himself chased out of Australia for overstaying his visa, then chased all over Indonesia for referring to First Lady Suharto as “Madam Ten Percent.” He eventually cleaned up his guidebooks to ensure distribution, but he still has all his original notes, from Australia as well as Asia, and it might be time to take another look at them.