By RON LANE

AT 12.30am on 23 July 1916, 22 days after the start of the Battle of the Somme, the Diggers of Australia’s First Division were moving into position under the cover of darkness.

Little did they know their objective was about to become their hell on earth. Its name was Pozieres.

Australia’s official military historian Charles Bean described Pozieres as: “The one place on earth most densely sown in Australian sacrifice”.

According to one witness, the survivors of the First Division “looked like men who had been in Hell … drawn haggard and so dazed they appeared to be walking in a dream and their eyes looked glassy and starey”.

For the first three days of the battle, the First Division suffered over 5300 casualties. However this was just the start, for until the final withdrawal of all Australian troops on 3 September the various divisions, First, Second and Fourth, who had served in the battle on a rotation system, suffered an estimated 7000 killed and 16,000 wounded. Of those killed 4112 were never found or identified, due to what can only be described as the most intense artillery barrage of the entire war.

When we compare the casualties of the Gallipoli campaign, 8700 killed and 17,000 wounded over a period of eight months, to Pozieres – 7000 killed 16,000 wounded in only six weeks – we begin to understand the intensity and the suffering that was Pozieres.

It is interesting to note during the eight-month Gallipoli campaign, nine Victoria Crosses were awarded compared to five in just six weeks at Pozieres. These figures, according to They Dared Mightily, the history of our VC recipients, again tend to emphasise the brutality of the fighting for this small French Village.

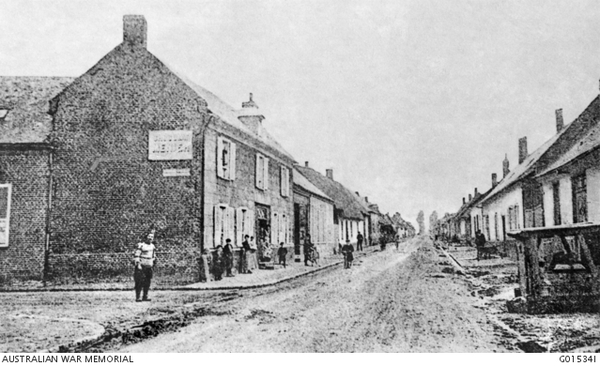

Before the commencement of hostilities in 1914, Pozieres was a small French country village of 300 souls. They tended their cattle and vineyards. The houses were small, dowdy and close together. Poet John Masefield described it as “poor and without glory except for its lovely trees”, but it had the misfortune of being situated on what the military termed, high ground.

Proceeded by a seven-day artillery bombardment that could be heard in the streets of Kent, the Battle of the Somme was intended to break the stalemate of the trench warfare that had existed on the Western Front since 1914. Unfortunately Pozieres was a major objective.

Situated as it was, the area surrounding Pozieres was interwoven with German trenches with good fields of fire in all directions.

Early on the morning of 15 July and again at 6pm on the same day, the British had attempted to take the village. They failed. They tried again two days later and confronted by a defense system of 10 machine gun nests, the attacking British were annihilated.

Following these disasters, General Haig in conference with senior officers decided the Australian First Division would be used. Going in behind a well-planned and intense artillery barrage the Diggers achieved their objective and over the next three days took and secured the village.

However in doing so they caused a bulge in the German front line. As a result the Diggers were surrounded on three sides by an enemy determined to retake the village.

The Australians faced what is now considered the heaviest artillery barrage of WWI. It is estimated the British alone fired thousands of rounds into the village. Add to this the German shells coming in from three sides and the village of Pozieres ceased to exist.

After those first three days what was left of the First Division had to be withdrawn and replaced by the Second. This was the start of what was described as the “rotation of death”.

Twelve days of defending the village plus taking high ground known as the Windmill, they too had to be withdrawn and replaced by the Fourth Division.

They continued to consolidate and finally took Mouquet Farm just to the north, but German counterattacks finally retook the farm.

Then on 3 September, 1916, all Australian Forces were withdrawn from the area. There were not enough soldiers left to continue the fight.

Lieutenant Arnold Brown of the 25th Battalion, which was virtually annihilated at Pozieres, said: “The Pozieres battlefield will become a sacred place for Australians. It will attract pilgrims, perhaps more so than any other place.”

However Brown had not envisioned the allure of Gallipoli or the brightness of its myth.

Now the village has been rebuilt. In the main street “Le Tommy Cafe” caters for pilgrims from England and Australia; and behind the restaurant is an open air museum.

The Diggers of Pozieres must not remain unknown.

Lest We Forget.